This is the SBBN entry for The Barrymore Trilogy Blogathon, hosted by In the Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood. Make sure to click here and enjoy all the fantastic entries!

This is the SBBN entry for The Barrymore Trilogy Blogathon, hosted by In the Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood. Make sure to click here and enjoy all the fantastic entries!

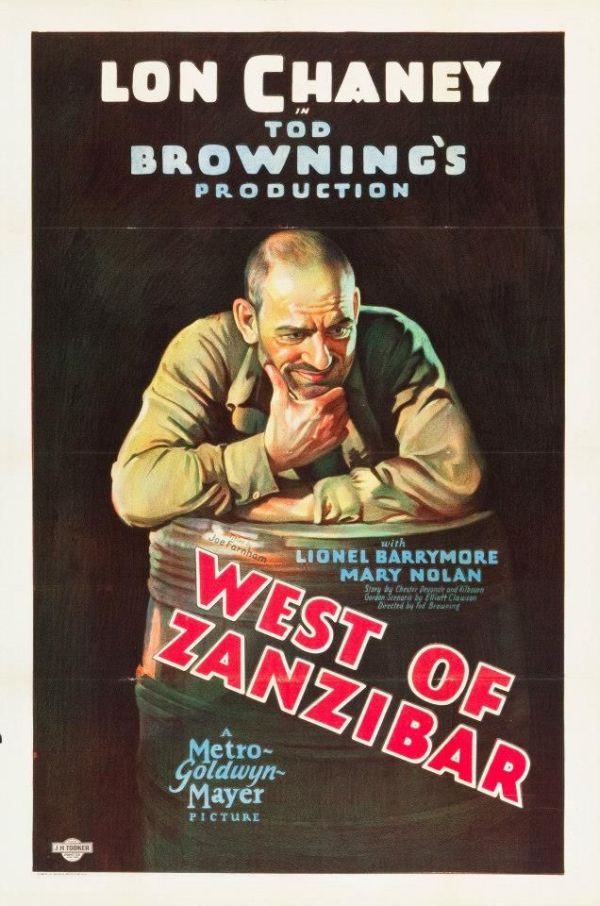

Poster art courtesy Jorday Jaquay on Pinterest.

***

Lon Chaney was one of the biggest movie stars of the silent era, a master of disguise whose dedication to his craft was alternately admirable and obscene. Though a true pioneer in the art of movie make-up, his technique bordered on the ludicrous at times. It’s easy to respect his dedication in terms of body manipulation, a dedication that frequently caused him serious pain, but in our modern age, it’s hard to forget that Chaney’s grotesques were nearly always the result of a moral failing. That is, most of the disabled and disfigured characters he played were portrayed as people who deserved their fate because of some past deeds or inner ugliness. Further, these characters differed wildly in appearance, yet so often found themselves in the same basic situations, film after film, that his skill starts to feel, after the fifteenth film about a malformed malcontent pining for a lost love, like gimmick rather than substance.

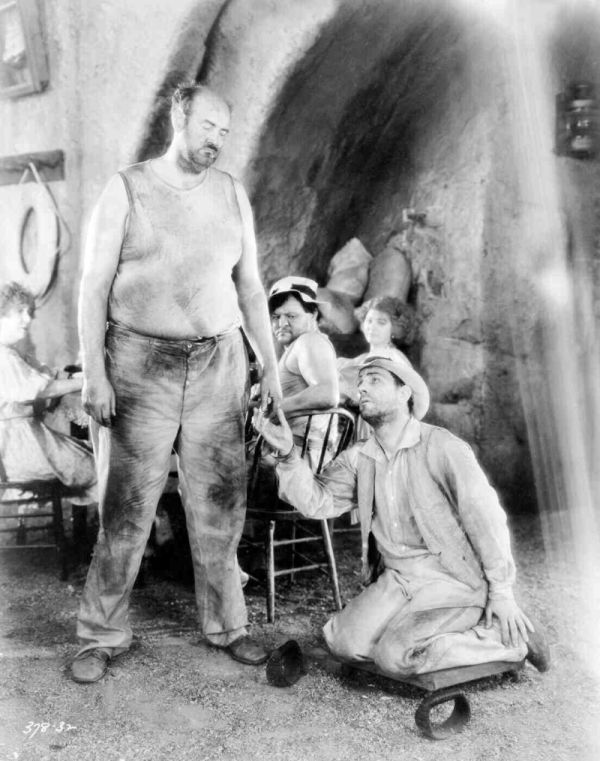

Lon Chaney, Mary Nolan, Warner Baxter and Lionel Barrymore. Photo courtesy George Eastman House, who label Kalla Pasha as “some guy with a beard.”

Lon Chaney, Mary Nolan, Warner Baxter and Lionel Barrymore. Photo courtesy George Eastman House, who label Kalla Pasha as “some guy with a beard.”

Some of this cinematic repetition, however, is surely due to Chaney’s frequent collaboration with horror director Tod Browning. For ten films, beginning in 1919 and culminating in 1929, Browning directed Chaney in what are now some of his most famous roles. West of Zanzibar (1928) would be their ninth collaboration, one of their most successful pairings, but one which came toward the end of their careers, although they didn’t know it yet.

Like David Cronenberg decades later, Browning was fascinated by the relationship between outward physical appearance and inner psychology, and Chaney’s skill in the art of transformation was Browning’s most trusted muse. Despite approaching these tragic characters with humanity, Browning was still a Victorian at heart, which is why he so frequently chose for his films the recurring theme of women’s infidelity, an act so destructive, at least in Browning’s vision, that it would ruin lives for generations and turn kind men into cruel villains.

And that is exactly what happens to Chaney’s characters time and time again, most notably as magician Phroso (Chaney) in West of Zanzibar. When he learns his beloved wife is fleeing to Africa with the scoundrel Crane (Lionel Barrymore), Phroso begs Crane to let her stay. As Phroso pleads, Crane pushes him off a balcony, rendering him paraplegic. This, in typical silent horror fashion, signals Phroso’s immediate metamorphosis from raging milquetoast to subhuman sociopath. One year on, his wife returns with a baby in tow, just in time to die of the typically Victorian and unspecified causes that all fragile and flawed women in tales like this expire from.

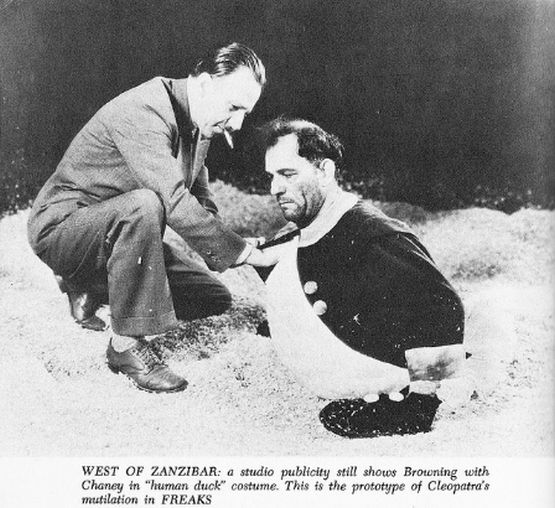

Chaney as Phroso, courtesy Doctor Macro.

Chaney as Phroso, courtesy Doctor Macro.

Phroso vows revenge upon both the bastard child and Crane, and a quick flash to seventeen years later, we see the psychotic results. Now known as Dead-Legs and living “west of Zanzibar” — probably in modern-day Tanzania — he’s the owner of a nasty little business that specializes in stealing ivory from Crane, who lives somewhere nearby. Dead-Legs has also been paying handsomely to keep his wife’s daughter Maizie (Mary Nolan) in a whorehouse in Zanzibar. Now seventeen and apparently one of the madam’s best ladies, Maizie is lured to Dead-Legs’ lair, forcibly drugged, humiliated and sexually abused by the men in Dead-Legs’ employ. After she’s thoroughly destroyed, he summons Crane to show him what’s left of his daughter, but a surprising revelation destroys his plans for revenge.

Despite his reputation for campy, hammy performances, Barrymore delivers a moderate and modern performance in West of Zanzibar. He was a veteran actor by 1928 — and one of Lon Chaney’s personal friends — so he was more than prepared for the role, but even Barrymore must have felt somewhat stymied by the fact that the character has no backstory, or even reason to exist beyond plot device. Crane appears fully formed at the beginning of the film, his caddish behavior already on full display in the dressing rooms of the theater where Phroso and his wife are performing. Where is this theater? Why is Crane there instead of in Africa tending to his business?

Yet Barrymore manages to imbue Crane with a subtle humanity that elevates his performance above that of others in the film. Early on, when Phroso begs Crane not to leave with his wife, Barrymore’s comparative calm steals the scene right out from under Chaney’s heavily powdered nose. Later, when Phroso (now Dead-Legs) confronts Crane, Barrymore manages to play this man who has done such terrible things as just another man of the world, and suddenly you realize how Phroso’s wife, and probably a dozen other women like her, could have fallen so hard for him.

Promotional photo courtesy Matthew C. Hoffman’s article at The Rediscovered.

Promotional photo courtesy Matthew C. Hoffman’s article at The Rediscovered.

In fact, Barrymore’s performance is more in line with that of male leads in pre-Codes than silents. In silents, women (especially in Browning’s films) were usually stripped of all agency, powerless against the machinations of men, regardless of whether these men were villains or some version of a good guy. In pre-Codes, women had freedom and agency and choice, and as such the male leads were rarely the outsized lunatics or overwrought romantics seen in silents. Instead, they were subtle, often caddish (whether villains or not), straightforward and emotionally collected. Barrymore’s Crane is one such guy, a man with the outward demeanor of a genial bounder, who turns out to have something much darker and sinister underneath the surface.

The version of West of Zanzibar we enjoy today is truncated, in part because of some rather rough scenes being deleted by the studios. According to historian Michael Blake, quoted here at the excellent Park Ridge Classic Film, Phroso originally finds his way to Africa while hunting down Crane; once there, he and his two sleazy henchmen, along with the alcoholic Doc (Warner Baxter), play con games to make a little coin. One of these games involved Phroso disguised as “the human duck,” a conceit removed from West of Zanzibar but later used in Browning’s Freaks (1932).

West of Zanzibar features sharp story-telling, psychological horror and a quick pace, and is just a touch ahead of its time; both Warner Baxter and Mary Nolan give modern, strong performances that complement Barrymore’s, and anticipate the pre-Codes as much as Barrymore’s performance does. Enough actors in the film went on to careers in talkies that it’s easy to imagine them speaking their dialogue; in fact, West of Zanzibar would probably wear better as a talkie, though one of the big reveals hinges on the fact that this is a silent film. (It should be mentioned that the film was remade as a talking picture called Kongo in 1932, this time with Walter Huston in the lead — he had been the lead in the Broadway version several years earlier — though this remake is a far inferior film to West of Zanzibar.)

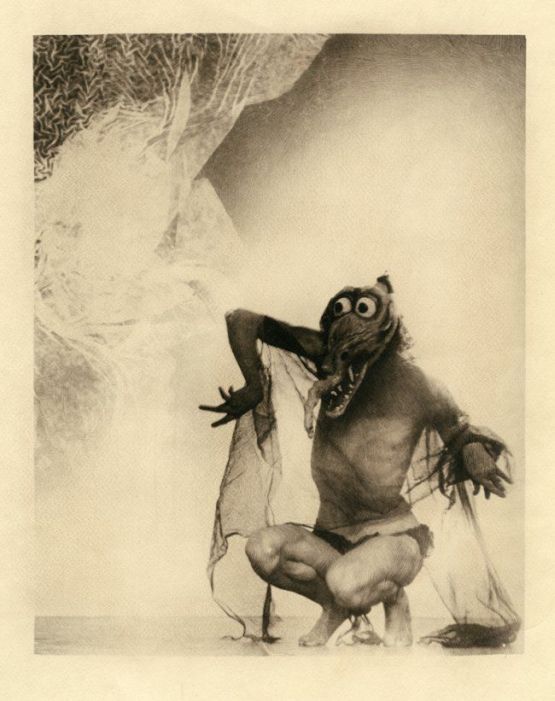

From a deleted scene, courtesy Doctor Macro.

From a deleted scene, courtesy Doctor Macro.

There is more than a hint of Colonel Kurtz in Dead-Legs, and much of West of Zanzibar, and the Broadway play it was based on, derives from themes introduced in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Still, the film fails on a few levels, most notably in its strange plot contrivances designed to reassure audiences that, though Maizie had been abused, she was not abused by Dead-Legs. There are also the usual lingering shots on the film’s star, common enough for the silent era, but which (unintentionally, perhaps) frame the disabled as freakish and play into Chaney’s cult of personality.

The scenes of Dead-Legs performing “voodoo” are generally ridiculous, in part because his mask looks like Gonzo the Great.

The tribal masks are nicer and more convincing.

The masks were made by William Mortensen and used in an artistic study photographed by Mortensen titled “The Incubus.” A fantastic article about Mortensen can be found here at The Guardian, which briefly about Chaney’s influence on Mortensen’s art.

The film’s racism is another weakness; racism was nothing new in 1928, of course, but where the traditional negative value attributed to “blackness” is subverted in Heart of Darkness, in West of Zanzibar, is it bastardized back into the original centuries-old trope of black as bad, white as good. In doing so, it unintentionally undermines the psychological exploration in the story, turning it into a basic morality tale, and rendering the Africans’ vague voodoo ceremonies a mere excuse to engage in Colonialist stereotypes of cannibalism and savagery.

Interestingly, Barrymore’s character treats the native peoples of the area far better than Dead-Legs and his minions do, though what that means is entirely unclear. Fans of silents and early Hollywood films will know that there was an enormous amount of inconsistency when it came to issues of race in movies, and even in individual movies, an actor’s style could cause one character to seem to be sympathetic when that was not actually intended in the script.

As quoted in Brian Darr’s excellent article on West of Zanzibar in Senses of Cinema, historian Kenneth M. Cameron called the film “the best movie ever made in America about ‘Africa’,” by which he meant “the near-mythical continent of hostile inhabitants and unseized opportunities as portrayed by Western storytellers in need of an exotic ideal,”, i.e. a “white hell.” In this context, Barrymore keenly portrays one of the friendly everyday demons populating this “white hell,” the kind of guy who happily consigns himself to a torturous afterlife because, hey, that’s where all the fun is.

Still, for sheer, lurid melodrama, you can hardly go wrong with West of Zanzibar. The plot is as salacious and upsetting as any of those fantastic Technicolor soap operas of the 1950s and 1960s. Though Warner Baxter and Lionel Barrymore would go on to solid careers, both winning an Oscar within just a few years of West of Zanzibar, Tod Browning and Lon Chaney wouldn’t fare as well. Browning’s career would end thanks to the disastrous reception to Freaks just four years later, while Chaney would be diagnosed with cancer only a year after West of Zanzibar was released, and dead from the disease just one year after that. Despite being a sad reminder of what could have been, West of Zanzibar remains a staple of late-era silent movie making and one of the best Browning-Chaney collaborations.

An earlier version of this article appeared at Spectrum Culture.

I liked how you compared this film to the “Technicolor soap operas” of the 50s-60s. Those films can be a grind at times, but that comparison has actually made me keen to see this film sooner rather than later.

Also: I loved the images you’ve posted. They offer a good sense of the film’s atmosphere.

Thanks so much for participating in the blogathon. I’ve only just got around to reading the entries now, and I enjoyed reading yours. Excellent review.

I’ve also just announced a new blogathon that you might be interested in participating in. The link is below with more details

https://crystalkalyana.wordpress.com/2015/08/17/in-the-good-old-days-of-classic-hollywood-presents-the-lauren-bacall-blogathon/