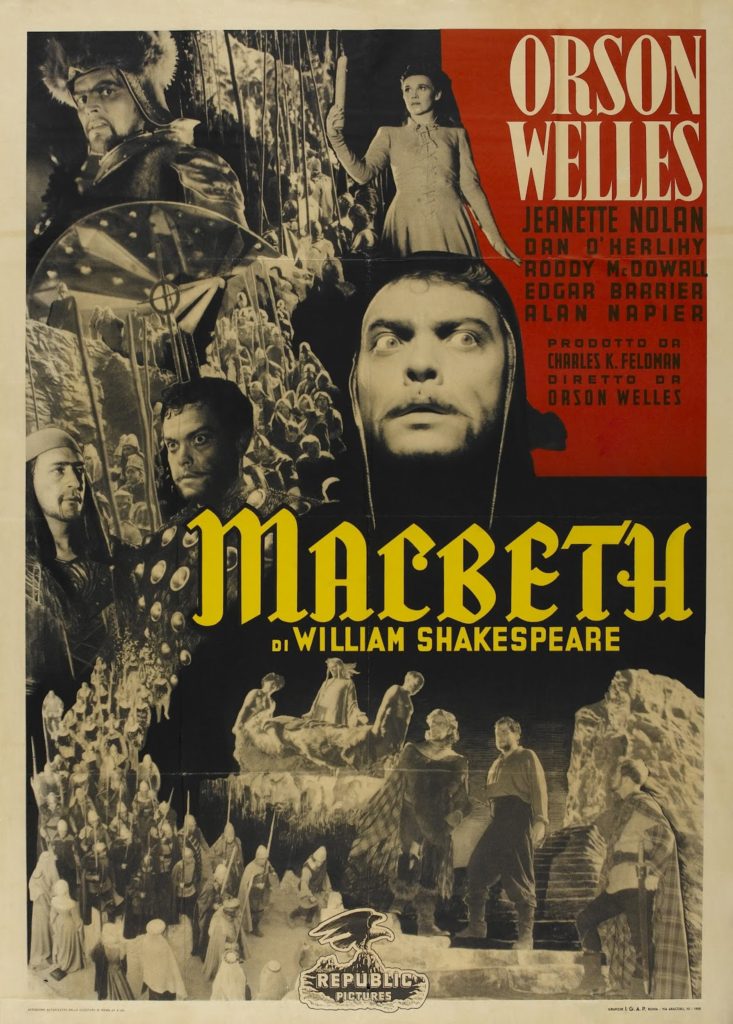

It’s difficult, even for a very forgiving fan like me, to not wonder if much of the now-celebrated innovations of Orson Welles’ later-career output weren’t just the manifestation of restlessness and hostility. Macbeth (1948), Welles’ adaptation of the Scottish play, was not the first film of his finished by someone else, but it would be the first of many of his films to be released in multiple versions. Audiences, critics and studios alike found his work confusing, indulgent and wildly out of sync with the times. It’s a more or less straightforward adaptation as far as plot and character motivation goes, but visually and conceptually, Welles’ Macbeth was probably one of the oddest films anyone of the time had ever seen.

As Macbeth (Welles), a celebrated Scottish soldier in the 11th century, and his general Banquo (Edgar Barrier) are riding home, they stumble across three gruesome witches, all praising a clay effigy of Macbeth and promising he is to become King of Scotland. Though Macbeth is unsure of his destiny, Lady Macbeth (Jeanette Nolan) is not, and urges her husband to kill King Duncan (Erskine Sanford) and essentially chase off his son Malcolm (Roddy McDowell) so he can claim the throne for himself. Once the deeds are done, more killings are required, the paranoia, guilt, madness and death are the result.

Macbeth is an uneven film, surely intentionally, but its schizophrenic nature doesn’t always work. Welles is a fine if workmanlike Macbeth, while Jeanette Nolan is revelatory as the over-heated Lady Macbeth. Critics now and then dismiss her performance, though much of her restraint surely comes from the censors’ requirements, and many of the reviews are of the truncated 1950 version of the film, which edits her performance in two key scenes, and not for the better. Nolan and Welles are well matched in their scenes together, both artistically and physically; Welles’ imposing figure towering over Nolan’s sharpens Lady Macbeth’s edges and highlights the false king’s insecurities.

Amongst the fine performances are strange ones, like Roddy McDowall, who even by 1948 should have been campy perfection — completely unrelated, but if you haven’t seen his “Columbo” episodes then you need to stop what you’re doing right now and go to Netflix — turns Malcolm from honorable man seeking vengeance to a mildly confused teenybopper. Edgar Barrier is a completely useless Banquo, while Alan Napier is the hammiest I’ve ever seen him, and I’ve seen The Mole People, so that’s saying something.

The idea of Welles doing a faithful interpretation of Macbeth is a somewhat odd one, as a decade earlier he had become famous for staging what is commonly known as “Voodoo Macbeth,” featuring an all-black cast with the setting changed from Scotland to Haiti. Reaction to his Federal Theatre Production ranged from praise to overwhelming praise and Welles, only 20 at the time, was an much an overnight sensation as the play itself. Radio and cinematic success followed in short order, then his career came crumbling down even faster than it was built.

By 1948, the 33-year-old Welles was a has-been who was barely able to get work. In 1946, after spending several years working primarily in radio, he cut a deal with International Pictures. The result was The Stranger, and even though it came in under budget and turned a tidy profit, Welles lost a four-picture deal with International that had been promised him. Turning to Columbia Pictures, his next film, The Lady from Shanghai, was considered a complete embarrassment. So too was Macbeth, which Republic Pictures held on to for over a year before releasing, after preview audiences savaged the 1948 version of the film.

I don’t want to spoil it for you, but things don’t go well for Macbeth.

Most of the complaints about Macbeth were due to its production design; Welles’ plan was to make an A-list film with a B-movie budget. (John L. Russell, cinematographer for Macbeth, a decade later would shoot Psycho for Hitchcock, another A-list B-movie, and a far more successful one.) The result of Welles’ budget-minded production is the kind of surrealism that one cannot imagine the general public being able to grasp in 1948. The characters speak, though their mouths don’t move; action is caught seemingly accidentally on the edge of the frame and can barely be seen; the focal point of a shot will be not the actors, but a large, ugly puddle at their feet. Everything is moist and dank and unappealing, and so cold that you suspect several actors developed pneumonia by the end of the shoot. Welles had warned the press that his Macbeth was “a violently sketched charcoal drawing of a great play,” but it was no use; the critics were hostile and unkind.

Exciting hats!

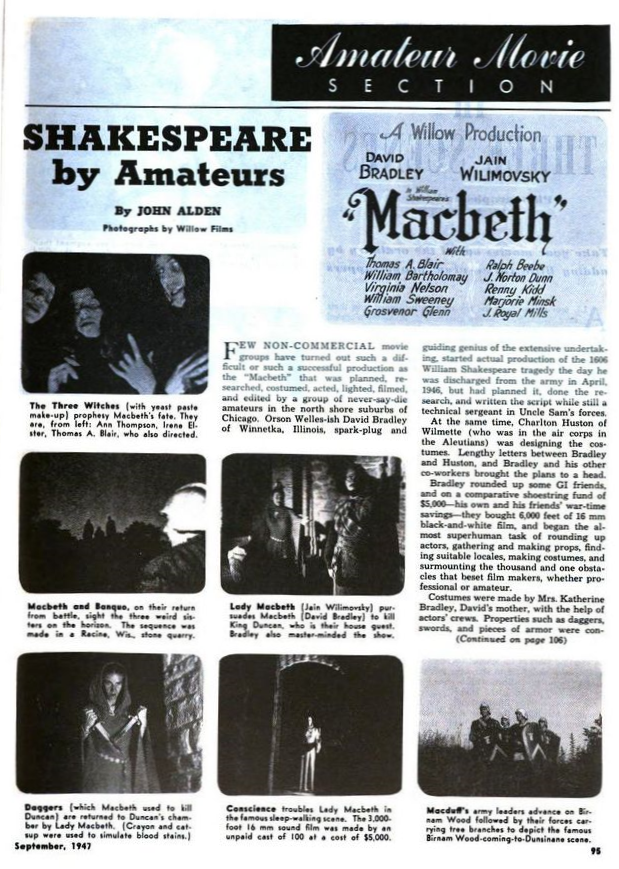

Macbeth is the first feature-length talking film of this particular Shakespeare play, though some consider it to be the second, with the honor of first going to an amateur production made in Chicago in 1946 that only saw local release.

From Popular Photography, September, 1947. Note that David Bradley as Macbeth is called “Orson Welles-ish.”

The just-released Blu-ray version of Macbeth from Olive Signature includes both the original 1948 cut at 107 minutes, and including the soundtrack featuring the actors using a Scots burr that irritated the studio, as well as a second disc with the 1950 version, trimmed to 85 minutes and the accents eliminated. Also included are a booklet with an essay by Jonathan Rosenbaum, several interviews about the making-of and restoration, an excerpt of some of the 1936 “Voodoo” version of Macbeth stage play, commentary, and a documentary on Republic Pictures.