Penelope (Natalie Wood) is a bored housewife who steals things for fun. Her inattentive husband runs a bank, which goes a long way toward explaining her kooky scheme to rob her husband’s bank of $60,000. She confesses this to her psychiatrist (Dick Shawn) and attracts the attention of a police officer (Peter Falk), and they of course both fall in love with this pretty, wacky free spirit.

Penelope goes through a series of allegedly funny hijinks and flashbacks and ultimately decides to change her ways. She tries to tell her husband she’s the thief but he won’t believe her, so she plans to return the jewelry she stole from her society friends over the past months, thinking this will prove that she is a thief, but none of them even acknowledge it was theirs in the first place. Her condescending husband is convinced she was lying for attention, the psychiatrist and police officer both know she’s guilty but won’t turn her in, she returns the bank’s money, happy ending, whee.

Penelope, like many wacky 1960s comedies, suffers from predictability. The wackiness was forced, Ian Bannen was Mr. Snoozeorama, Natalie Wood didn’t seem to want to be there, etc. etc. etc. However, I had a personal aversion to the film, one I can’t explain all that clearly but which began early on when the psychiatrist (Dick Shawn) says something to the effect of “Depression is a vacation most of us can’t afford to take.” Such sloppy writing. This is a light comedy, so there was no reason to inject any hint that the mentally ill are just faking illness into the context of the film. Maybe the intent was to show the psychiatrist was terrible at his job, I do not know. What I do know is this obvious one-liner was written to play as humorous and quotable, but instead invokes the exact wrong threads of thought into a light-hearted discussion between two main characters.

Jonathan Winters in a flashback cameo as a lecherous teacher chasing schoolgirl Penelope around during chemistry class.

Jonathan Winters in a flashback cameo as a lecherous teacher chasing schoolgirl Penelope around during chemistry class.

In Penelope, the lead’s rebellious streak is played as inseparably a product of the times. Flashbacks depict Penelope as a member of the late beatnik counterculture in the early 1960s, and we’re lead to believe she continued on to become a member of the pre-Summer of Love hippie culture, but then found herself stifled in her new upper class, boring life.

Yet the inevitable resolution from the first frame of the film was that Penelope would learn to be happy conforming in the life she has married into, which she does, with very little effort on her part. The counterculture elements were likely added only to appeal to more audiences, again undermining any real context the film might have created otherwise.

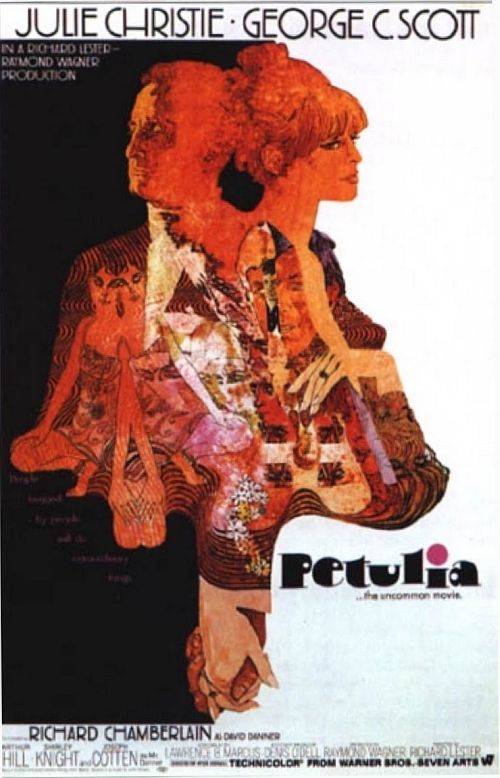

Two years later, Petulia took much the same premise but in a decidedly darker direction. The women in both films are bored, eccentric, beautiful, stylish, and became upper class when they married staid, rich men. These were women whose wacky nature was intended to embody the free spirit counterculture of the 1960s. Yet the counterculture had passed them by, but Penelope neither realized or actively cared. The tone of that 1966 film thus ended up as a sleek Hollywood version of what a free spirit might look like, as imagined by people who had never known a true free spirit in their lives.

Meanwhile, Petulia’s life is all about her misfit status and her constant concern with fitting into the culture she wishes she could belong to. We eventually learn her smile-filled whimsical nature is self-consciously eccentric, something readily apparent by the tuba-stealing scheme that remains the most famous moment in the film. In any other film, the kooky girl would steal a tuba and effortlessly deliver it to her lover (a doctor, played by George C. Scott), who would be charmed and enchanted, then they would return the tuba together having shared a fun, bonding moment. Petulia wants that, expects it even, but instead gets an awkward trip with a tuba, injuries, confusion, and irritation — you know, reality.

Petulia also expects to engage in some of the uninhibited sexuality of the 1960s. She talks a big game at a snooty upper class party where she hooks up with an equally out of touch doctor, a man who spent his mid-life crisis divorcing his wife because he thought he could score some ‘tang thanks to this free love thing all the kids are talking about nowadays. This upper class party features entertainment by Big Brother and the Holding Company, by the way, which only serves to highlight how far removed from hippies and free love and revolution Petulia and her doctor really are.

SBBN faves Barbara Colby and Austin Pendleton in small roles in Petulia. Tragically, Colby was murdered in 1975. The murder was never solved.

SBBN faves Barbara Colby and Austin Pendleton in small roles in Petulia. Tragically, Colby was murdered in 1975. The murder was never solved.

The life she coveted had passed Petulia by as much as it had passed Penelope, only Petulia was aware of it. Penelope never did achieve awareness, at least not overtly, because she came to realize she never wanted a free life anyway. Her wild flights in her youth achieved nothing but giving her just enough socially-acceptable wackiness to make her irresistible to every man she encounters.

Petulia however achieves nothing positive from her desperate attempts to embody the counterculture, which is unsurprising as she is as much of a fraud as the doctor is. He doesn’t want to be a hippie or outsider, he just wants booty. She doesn’t want to be a hippie, she just wants to escape her problems. Petulia was, in a way, Richard Lester’s answer to Hollywood’s habit of representing counterculture in the shallow, profit-based terms seen in Penelope. But it goes much farther than that, of course, questioning the existence and purpose of the counterculture itself as well as the motives of those drawn to it.

Petulia however achieves nothing positive from her desperate attempts to embody the counterculture, which is unsurprising as she is as much of a fraud as the doctor is. He doesn’t want to be a hippie or outsider, he just wants booty. She doesn’t want to be a hippie, she just wants to escape her problems. Petulia was, in a way, Richard Lester’s answer to Hollywood’s habit of representing counterculture in the shallow, profit-based terms seen in Penelope. But it goes much farther than that, of course, questioning the existence and purpose of the counterculture itself as well as the motives of those drawn to it.

As usual, you’ve introduced me to films I never knew existed! I think I’ll probably skip Penelope, but Petulia sounds intriguing. I’ve added it to my Netflix queue. Thanks for the recommendation!

thanks for this saddening but trenchant post. I always felt Petulia was overrated, but through your lens here the weird relation to the counterculture is understandable – yea, indicative of the counterculture’s decline itself. Having just reviewed Skidoo recently, I know how hard it is to rifle through the jaded fear of the Hollywood elite over the hippies their compelled to depict, in order to find the nuggets of genuine insight. Petulia sees through its own facade, but is that the point? I do love the acting of George C. Scott with his ex-wife, but he never seems to connect with Christie the way, say, William Holden did with BREEZY.