Caution: Spoilers Ahead!

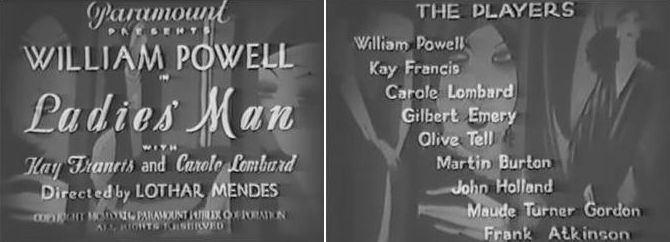

One of the first lessons for fans of early film is perhaps also the hardest: many pre-Codes and early talkies are simply no good. The technological limitations, the era, the changing morals and styles, even when acknowledged, fail to fully excuse many of these indifferent programmers. Ladies’ Man (1931), with its unparalleled cast of William Powell, Carole Lombard and Kay Francis, on the surface promises much, but unfortunately exhibits the particular type of cinematic laziness so common with the lesser pre-Codes, a formula that mixes a scandalous story with shimmering gowns and lovely sets, the goal being to create a profitable programmer and nothing more.

Ladies’ Man does its amazing cast a disservice by reining in their natural charisma, and much of this incompetence can assuredly be traced back to director Lothar Mendes. The dialogue is tiresome and stilted, the kind of thing one would expect in an early 1929 talkie, and is made worse by the deliberate silencing of the delightful, trademark patter of all three stars. Occasionally they shine despite an obvious dampening influence, but for most of this film’s 75 minutes the three speak slowly, adding unnecessary pauses and falling into a dull monotone that may very well have been an unconscious protest against the demands of the director. Only Olive Tell as the overwrought society matron shows consistent vocal emotion, if one can call falsetto politeness punctuated with a shrill faux-British warble “emotion.”

Less than two years earlier, Mendes had directed Dangerous Curves (1929) and failed at garnering even remotely passable performances from any of the stars. It’s tempting to believe Mendes simply could not direct, which is the conclusion Mordaunt Hall made when reviewing this movie in 1931. However, the year after Ladies’ Man, Mendes directed the superb Payment Deferred (1932), so that theory falls short. And Paramount did not suffer from outdated technology, as other films from the studio at about this time include Raffles (1930) and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), both with fine sound and dialogue. It’s a mystery then why Ladies’ Man fails so spectacularly, and not the fun kind of mystery involving poisons and trap doors, either.

Part one of the lazy pre-Code formula is skeeve, and while the plot of Ladies’ Man isn’t exactly fresh, the sleaze factor is astonishingly high. Society gigolo Jamie Darricott (William Powell) passes himself off as moneyed by living in a tiny closet of a room just to keep an address at a fabulous hotel. He comes complete with an unpaid valet and only two sets of dress clothes, but is charming enough to latch on to wealthy society matron Mrs. Fendley (silent film character actress Olive Tell) who feels neglected by her busy banker husband and starts an affair; at the same time, her spoiled and horny daughter Rachel (Carole Lombard) immediately propositions Darricott, so he sleeps with her, too. The two Fendley women know full well what is going on. There is nothing quite as sleazy as watching Rachel arrive at Darricott’s flat two hours after he’s banged her mother, hoping he’ll bang her next. This is 1931 and it is not so explicitly stated, of course, but that is exactly what is going on.

Meanwhile, Darricott has accepted some of Mrs. Fendley’s fabulous jeweled bracelets as payment in kind and sold them for $6,000 — that’s roughly $85,000 in today’s money, which I suppose indicates the level of cocksmanship Darricott possesses. He upgrades to a bigger apartment and more than two dress shirts and, one hopes, has finally paid the valet. Darricott has a history of selling bracelets from women over the years, which has attracted the attention of the police. If anyone in the audience didn’t understand what was going on, the helpful jeweler (stalwart character actor Clarence Wilson) explains to a police officer that bracelets leave less of a paper trail than checks, at least when it comes to paying gigolos for their wares.

Darricott meets Norma Page (Kay Francis) at one of the Fendley parties and immediately falls for her. She shows interest until told he’s a “ladies man,” the euphemism used for gigolo throughout the film. When he orchestrates a feigned chance meeting with her the next day she claims no interest in a pushy gigolo, but at the last moment changes her mind and agrees to a date. At the first glamorous nightclub the pair arrive at, they run into Mrs. Fendley, seething with jealousy. The second club is occupied by Rachel and her boyfriend, both horrifically drunk, Rachel reminding everyone that she’s sleeping with Darricott, which doesn’t bother her boyfriend one bit.

Norma is bothered, though, and despite being allegedly smarter than this, she continues on with the date and even goes back to Darricott’s apartment at the end of the evening. Rachel is already there, drunker and sicker and threatening either homicide or suicide, whichever, it obviously makes no difference to her. Chased out and humiliated by Darricott, she visits her father the next day and announces her mother is sleeping with the gigolo. Mr. Fendley already knows, the jeweler having informed on Darricott for no particular reason. Rachel tries to get her father to shoot Darricott but he feigns innocence about his wife’s affair, apparently because he’d already decided to murder Darricott anyway and was, I suppose, planning ahead for the upcoming murder trial which his daughter would undoubtedly be forced to testify at. As she leaves, her father the banker jokes about a busy day of evicting starving orphans and widows. This is about a year and a half after the stock market crash, mind you. Classy, classy stuff.

Meanwhile, the cinematic rehabilitation of Darricott begins. He excuses his life by explaining to Norma that he used to have a legit job selling bonds, but women would come in wanting bonds and they lacked “logic and common sense,” irritating him so much he was forced to bang them and leech off of them instead of working in an office. He continues by explaining that all wives work their husbands to death and then whine about being neglected, and he even complains that women will give jewels their husbands worked hard for to gigolos who don’t deserve it. Darricott is supposed to be a bit unlikeable, though the dual role of both cad and moral arbiter — he muses momentarily earlier in the film about the evils of people being drunk late at night — is unbelievable. By the time he says women essentially ruin men, we’re unquestionably meant to sympathize with him, though not so much that we are surprised when Mr. Fendley storms into the flat, shoots Darricott and then throws him off a balcony to his squishy, karmic end.

Daniel Bubbeo writes in The Women of Warner Brothers that the character of Rachel (Lombard) commits suicide in the film, which does not happen in the single print of this that has been floating around for decades, but it is very possible her suicide was originally intended. The last we see of her is as she leaves her father’s office, upset that Darricott has rebuffed her and that her father seemingly doesn’t care. Rachel’s character has no resolution, which is very noticeable at the finale, and I suspect her suicide was the resolution, cut from the final print.

As with a lot of misguided pre-Codes, everyone acts terribly dignified and proper while simultaneously behaving like a bevy of crazed, amoral baboons. The film, I would hope, at one point had the goal of presenting a coherent plot, but that goal was so thoroughly disregarded that foolishness is the only explanation for most of the character’s actions, and very few who watch this could possibly sympathize with even a single person.

The lazy pre-Code programmer formula also includes lovely sets, and on more than one occasion a scene lingers for some seconds after the action has ceased, obviously to show off the pretty scenery. Also featured in these programmers are fabulous gowns, and with both Kay and Carole, the film does indeed try to deliver. The costume designer is uncredited but must have been Travis Banton, who was at least responsible for one of Lombard’s gowns in this film. Yet the fashions in Ladies’ Man are sparse on taste and style, with awkward side slits and visible puckered seams on Lombard’s club wear; at one point, a strap breaks in what looks like an unintended wardrobe malfunction. The most egregious error is undeniably the flouncy taffeta thing with enormous sequined polka dots Kay is given to wear as her signature gown, its matching coat topped with a huge fur collar so heavy it had to be manually held up by Kay every time she wore it. While Banton would occasionally lose his mind and create something atrocious, it’s almost impossible to believe he could be responsible for the consistent sloppiness in Ladies’ Man.

This lovely promotional photo of the stars courtesy Carole & Co shows them in their two best gowns. Carole’s gown is the one Banton discussed in the article linked above.

This lovely promotional photo of the stars courtesy Carole & Co shows them in their two best gowns. Carole’s gown is the one Banton discussed in the article linked above.

The film is interesting in a Hollywood historical sense, mainly as one of two films Lombard and Powell worked on in quick succession before marrying in mid 1931. After finishing Man of the World (1931), according to the Hollywood Citizen-News, Powell and Lombard were supposed to next co-star in a film called Buy Your Woman. But Powell balked at the idea of playing a criminal, so they moved them both to Ladies’ Man, a film originally meant for Paul Lucas. The story was based on a serialization by Rupert Hughes that appeared in Cosmopolitan in 1929, with Herman Mankiewicz penning the screenplay.

Kay, meanwhile, was just beginning her ascent to stardom in 1931, and this good girl role was a stepping stone toward solid leading lady roles in 1932, most notably Jewel Robbery and One Way Passage, both also with Powell.

The shallow story and rushed performances keep this film from being anything significant. Completists will want to see it, and of course if you have the chance you probably should. It’s a rare pre-Code, very scandalous and with three major stars. There is one print that has been available from all the usual internet haunts for years, if you’re curious. It’s not a good print, but I’ve seen better movies in worse condition, and one takes what one can get when it comes to watching a film never released or shown on cable. But we humans have only so much time, and no one would blame you if you chose to skip this and just watch Trouble in Paradise again.

Have you ever seen the pre-code Warner Oland Fu Manchu movies? From what I’ve heard, they are decent in some respects, but terrible in others (like with the acting).

A well-thought review on a Lombard film I really haven’t thought about in some time…perhaps because I didn’t think much of it when I saw it many, many years ago; a programmer at best.

Carole frankly isn’t very good in it (though it’s not her picture by any means), but the 1931 Lombard is still learning her craft, not in any way to be mistaken for her 1936 or ’37 counterpart. Francis is gorgeous (as usual), and your description of the evolution of Powell’s character almost makes him out to be Godfrey’s evil twin — after losing his fortune, he takes it out on women. This guy would have probably done far worse to Cornelia Bullock than pushing her into an ashpile.

I’ve seen The Mysterious Dr Fu Manchu which was eye-rolling but, apparently, one of the better films. The sets were very nice, IIRC.

Thanks VP! You had some great info on the film on your blog, by the way, I was glad to find it!

I know some people have said they liked Carole’s performance, but she seemed bored to me, and I couldn’t blame her a bit.

A wonderfully detailed look at the film – congrats. Really impressive stuff and the stills you’ve found are really terrific. When I started reading I thought Id seen this movie, but it turns out I haven’t and was getting int mixed up with another Powell and Lombard movie of similar vintage, MAN OF THE WORLD, But hey – even if it’s not such a good movie it made for a fascinating article – cheers!

Love your review. I reviewed many of Jean Harlow’s pre-Code films and while one was good, the rest were just boring. Shame that many of these substituted scandal for substance.

Thanks Sergio and Kristen!

I agree that a lot of pre-codes got by on nothing but scandal. There’s a Mae Clarke movie called The Fall Guy where her brother-in-law needs oil for his saxophone keys, so he (played by a really irritating Ned Sparks) says loudly, “I need to pick up some speeeerrrrmmmm oil!” Mae says, “What?” So he says it louder: “SPPPEEEEERRRRRMMMMMMMMMM OIL!”

It’s supposed to be salaciously funny, but it is dreadful. It’s the best example of a pre-code trying too hard I’ve found thus far, though.