“I’m not standoffish, I’m inaccessible. Always have been.”

“I’m not standoffish, I’m inaccessible. Always have been.”

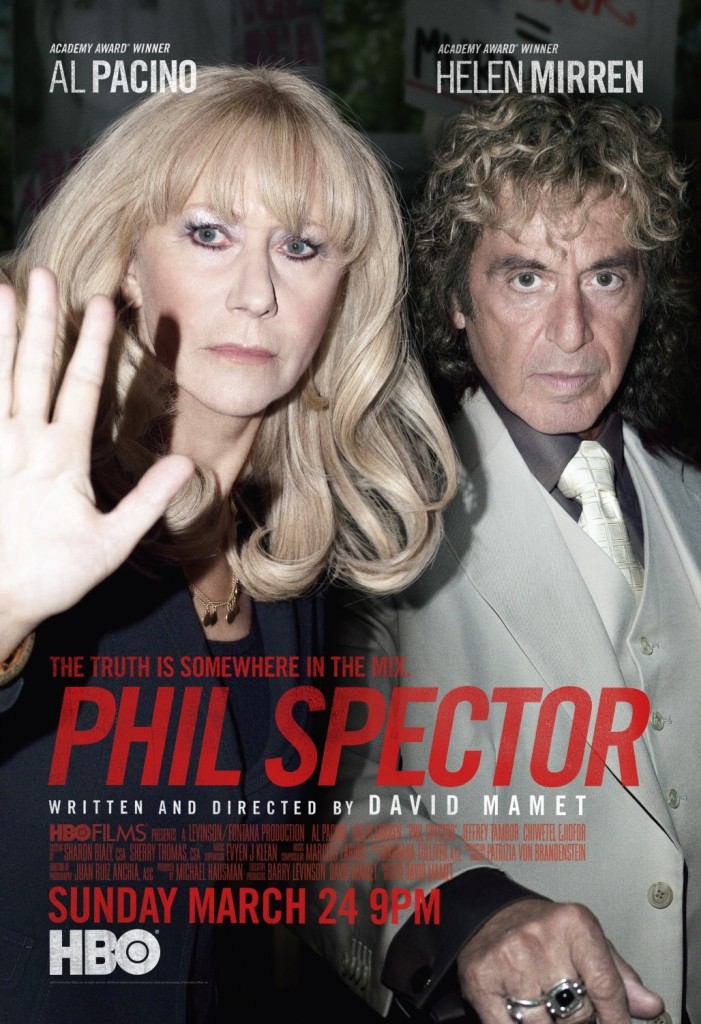

Al Pacino as Phil Spector in David Mamet’s Phil Spector (2013)

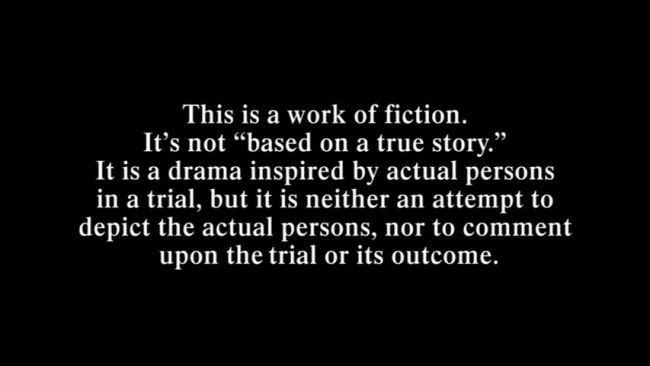

Just past the clumsily-worded disclaimer that opens Phil Spector is a movie that makes very little sense. Its title, its subject matter, its very existence is utterly dependent on the very real Phil Spector, his victim Lana Clarkson, and Spector’s resultant murder trial, yet right out of the gate, the film wants to have it both ways. The first act of the film almost succeeds in its attempt to be both fact and fiction, with some outstanding moments from Jeffrey Tambor, Al Pacino and Helen Mirren.

When the trial begins, however, the bullshit starts. Though some attempt was made in the Phil Spector publicity to present the film as a meditation on celebrity and a different take on the facts of the trial, it is, at best, a sad American version of Rashomon for the 21st century, where one of the storytellers is a cheesy made-for-TV movie. At worst, it’s an exercise in revisionist history done for some very specious reasons.

With the release of Phil Spector, we finally achieved undeniable proof that playwright and director David Mamet is a cranky get-offa-my-lawn kind of guy, someone who writes a scene that hinges on a character, surely born in the early 1980s, having no idea what a 45 RPM record was. Since 45s were sold as singles well into the late 1980s, it’s almost impossible to believe this character lived his whole life without seeing one. Never saw one in a store, never had an older sibling or parent or uncle bring out a 45, never saw a picture of one, never read a book or went to a website that mentioned 45 RPM records, never had a hipster college buddy who collected vinyl, never ate at a Shenanigans with a bunch of garage sale 45s nailed to the walls. Yet the fact that this 20-something didn’t know what a 45 RPM record was is important to the story, because it facilitates the first mention of why Spector did not get a fair trial.

From this moment of retconning, Phil Spector descends into frank lunacy. Far too much time is spent saying — repeatedly, by multiple characters in carbon copy dialogue — that Spector was going to be convicted simply because he was “freakish,” and because an irrational public wanted justice after O.J. Simpson was acquitted. This irrational public is trotted out in a couple of bad-faith scenes where protestors, all frothing at the mouth, unjustly frighten this nice little old man. He’s not the freak, says this film as it stomps its little feet, they’re the freaks!

Notably, despite time spent detailing how Spector was seen as significantly different from mainstream society, not once is his penchant for wearing clothing and wigs geared toward women mentioned. In fact, the film goes to great pains to put him in three-piece suits and loungewear that is eccentric but not feminine. The film is entirely unwilling to broach Spector’s cross dressing; this is even more interesting in light of the fact that the evening Lana Clarkson first met Spector at her hostess job — the night she was killed — she took Spector for a woman until she was told otherwise by her supervisor.

You won’t hear that in Phil Spector, because it’s a work of fiction, you see. A fact-based work of fiction where the characters are based on real people. It seems, however, that the fictional Phil Spector created by David Mamet was simply a slightly more masculine one, as defined by the common popular notion of masculinity, at least. Or perhaps he’s a slightly more noble-minded Spector than the real deal ever was; the same nobility, too, can be seen applied to defense attorney Linda Kenney Baden (Helen Mirren), but with even less reason or examination than afforded the Spector character.

Ultimately, Phil Spector falls flat as fiction: it relies so much on real world characters and details that it absolutely has to be approached as based on a true story. If it were nothing more than cinematic fanfiction based on a murder trial, it would be the kind of base opportunism I choose to believe David Mamet would not engage in. Still, it cannot be ignore that the film avoided interesting layers to the case that could have been explored with impunity if it were truly existing entirely under the “fiction” label, but Mamet tellingly chose not to take those opportunities.

Linda watches a cheesy B movie while surrounded by a variety of pills and vitamins. This is known as an average Tuesday night around my house.

Linda watches a cheesy B movie while surrounded by a variety of pills and vitamins. This is known as an average Tuesday night around my house.

Why Phil Spector exists or what it means to convey is entirely unclear, and not because of any supposed complexity, but because of its steadfast refusal to say anything of import. The actual meat of the movie is so slight that Pacino, when presented with a few sentences that comprise the best dialogue in the film, practically sings his lines with joy, delighted that something of substance has finally occurred. Unfortunately, Pacino, whose performances these days range from hammy to cheesy, gives the same overextended treatment to a final speech meant to tie the whole thing together.

But The Dude’s rug it ain’t. It’s a confused and silly speech which appropriates black culture and music in a way Spector did in real life, though not surprisingly, his career is regarded in the film as peerless, his one true glory. There’s no real drama in Phil Spector to resolve, anyway. It’s not that the film fails to answer questions, but it refuses to even ask them in the first place, resulting in that dreary combination of dull details and overwrought delivery, rendering itself completely useless.

Phil Spector is available from Warner Archive in a MOD DVD. Includes a special featurette titled “Conversations,” a promotional video with interviews from Mamet, Pacino, Mirren and more.

I think you’re a little too gentle with Mamet. The older he gets, the more arrogant, elitist and misogynistic he becomes. From what I’ve read about him recently, I’m convinced that this new work comes from a mindset that is no more nuanced than “Great men like Phil Spector shouldn’t be held accountable for harming peasants like aging B movie actress Lana Clarkson.” It’s like spitting on her grave. Disgusting. Sad, because there’s no denying Mamet once had great talent.

Maybe I am. I’m having a lot of trouble fully processing the film, because it seems on the surface like Mamet decided to “butch” Spector up, to praise him for co-opting black culture, to make his conviction a sort of perverse “white man’s burden” in that he’s “paying” for OJ Simpson’s crimes, then use this situation as a platform to rant against people who protest things like murder — I mean, how dare the proles act that way, right?

On the other hand, the lawyers, at least at first, repeatedly state Spector’s guilty and they’re just trying to defend him the best they can, because that’s their job, both practically and ethically. And it takes them forever to find a way to make the blood splatter not look like it’s the result of Spector shooting Clarkson, as they pick and choose which science to believe. I can’t quite chalk this up to 100% lunatic rightwing garbage, but I also have no earthly idea what the point of all this is, and I’m loathe to consider the film in purely political terms but I feel Mamet (and HBO) give me little choice in the matter.

A pretty good article on the political versus aesthetic in Mamet’s works is here, by Charles McNulty:

http://articles.latimes.com/2013/mar/29/entertainment/la-et-cm-david-mamet-notebook-20130331

I love Lana Clarkson, and in response to watching this I asked for (and got!) Amazon Women on the Moon for my birthday.