This is the SBBN entry for the Dynamic Duos in Classic Film blogathon, hosted by the Classic Movie Hub and Once Upon a Screen. Read all of the first day’s entries here at Classic Movie Hub and the second day’s entries here!

***

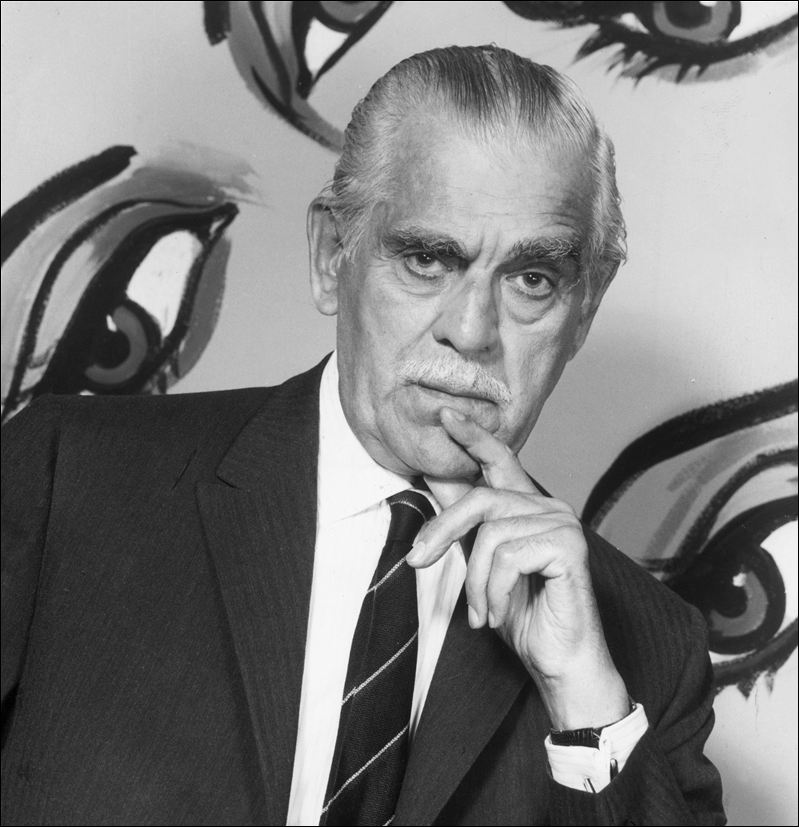

Boris Karloff never minded being typecast in horror films. Honing his craft in a touring stock company and relying on the approval of “unsophisticated” audiences, Karloff learned quickly what audiences responded to in a series of melodramas and murder mysteries performed in theatres across Canada and the United States. By the time he began to appear regularly in Hollywood silents, he was grateful for the work, no matter how small the role or how much makeup it required.

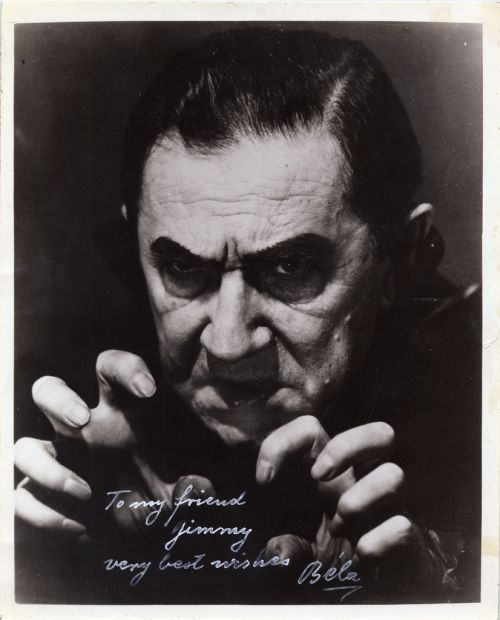

Bela Lugosi railed against the Hollywood system that would force him into horror films. He began his career on the Hungarian stage in a variety of roles, both featured and supporting. After moving to the United States and continuing his solid stage career, Bela originated the role of Dracula in the 1927 Broadway production of Bram Stoker’s novel. It was a hit, and Universal bought the rights for a cinematic version. Eventually settling on Bela for the lead — because of his Hungarian accent, the studios were reluctant to cast him — the film became a terrific hit. Bela Lugosi was catapulted into instant stardom, and expected a plethora of lead roles to follow.

One of these roles was as the Monster in Frankenstein, but Bela balked at the makeup, the lack of lines and the fear of being typecast in horror films. The studio, it seems, was at least a little relieved at Bela’s resistance, and the role went to Boris Karloff. Karloff was at first unsure about the part, but would later say he remembered the advice Lon Chaney, Sr. had given him years earlier: “Find something no one else can or will do.” The Monster, a character directly descended from Chaney’s silent era roles, was a risk Karloff felt he had to take, and the payoff was tremendous. After twenty years, Karloff, as Lugosi had just a year earlier, became a horror film legend, almost overnight.

Lugosi’s initial success in Hollywood evaporated quickly while Karloff’s grew. Though Karloff would later say Lugosi eventually came to trust him, Bela initially was unimpressed with his fellow actor. Still stinging from the loss of the role in Frankenstein, a part publicly promised to him then even more publicly withdrawn, he was jealous of Karloff’s success. Bela was also critical of the basic premise of the Monster, not entirely due to sour grapes, but because he felt actors were too often disrespected. Disguising an actor under layers of health-threatening makeup and giving him a role without lines or even a proper credit angered Bela, and there is some indication he felt Karloff was a bit of a traitor to the profession for taking the role. In turn, Karloff felt Lugosi never mastered the craft of acting, and his comments on Bela always tended toward pity rather than respect:

“Poor old Bela. He was really a shy, sensitive, talented man who had a fine career on the classical stage in Europe. But he made one fatal mistake: He never took the trouble to learn our language. Consequently, he was very suspicious on the set, suspicious of tricks, fearful of what he regarded as scene stealing.”

Universal, seeking to cash in on the name recognition of their two biggest and best-loved horror stars, cast the pair as co-stars as quickly as possible, even if they did not consider the two actors as equals. Bela Lugosi never achieved the kind of artistic, commercial or critical success Karloff did — he was paid less than half what Karloff made in The Black Cat, and that disparity would continue for the rest of his career — and jealousy was always a factor when the two shared the screen. Despite their tenuous detente, or perhaps because of it, Bela and Boris created some of the finest horror films of Hollywood’s golden age.

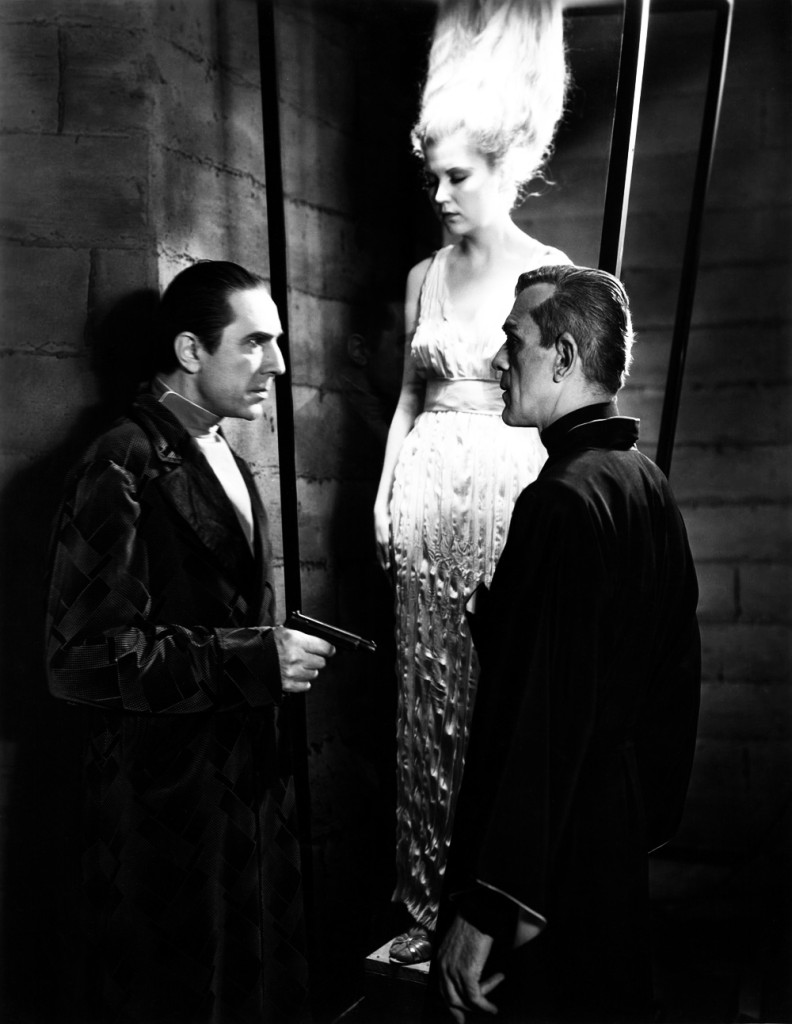

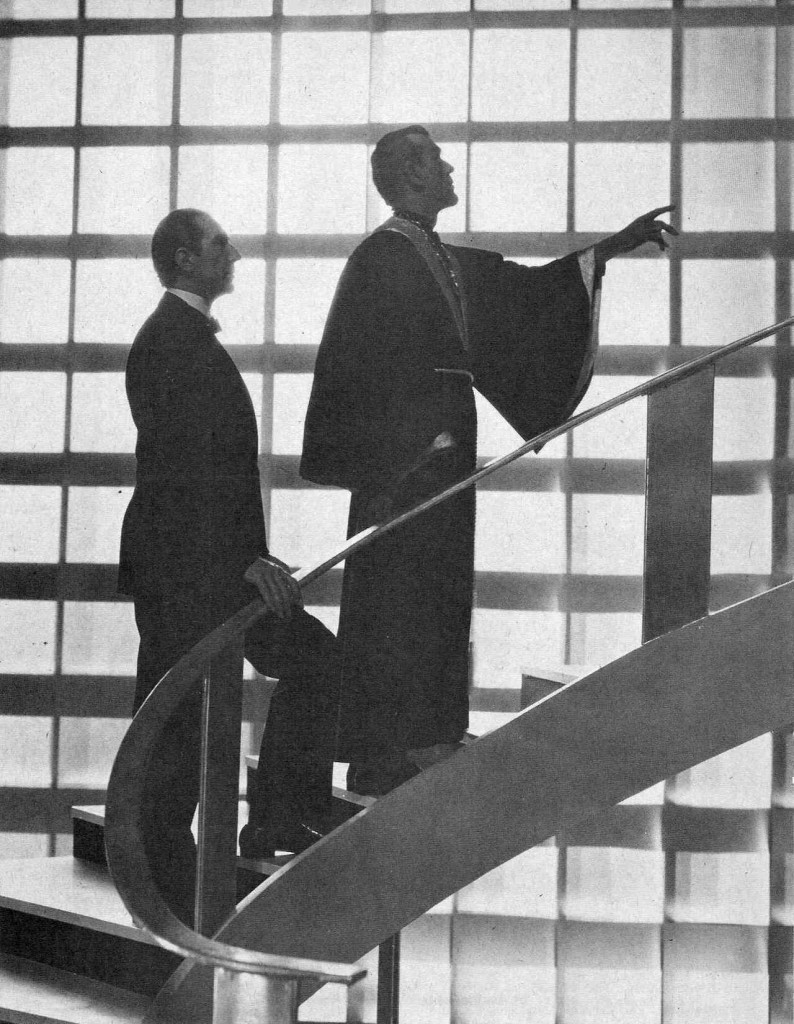

Karloff and Lugosi did not have an immediate chemistry together, though their emotional distance, and Lugosi’s pathological distrust, worked brilliantly in their first pairing in the now-classic The Black Cat. Borne from director Edgar G. Ulmer’s personal demons and what his widow later called an “unbelievable” obsession, The Black Cat (1934) is a psycho-sexual masterpiece, the macabre post-WWI tale of vengeance, lust, incest, necrophilia, sadomasochism, and repressed desire. Lugosi plays the anguished Dr. Wedergast, a man who has lost his wife and daughter to the perverse desires of Dr. Poelzig (Karloff), a stylish Satanist with a penchant for keeping his dead lovers in fetishistic vertical glass coffins.

The Black Cat was released mere weeks before the Production Code kicked in. In the pre-Code era, Lugosi was free to display an almost inhuman delight at reveling in the disturbed sexualities of his characters. Though he plays the hero, of sorts, in the film, his repressed Dr. Wernergast finishes off the diabolical Dr. Poelzig in a mostly implied but still horrific manner, one that can hardly be read as anything but the violent consummation of an inhumanly strong attraction between the two men.

Bela’s and Boris’ next film was a real oddity, the 1934 variety show The Gift of Gab. For decades, no prints of this film were found, though were presumed to be in the hands of collectors, including one whose print was stolen in the 1980s and never recovered. Gift of Gab became a Holy Grail of sorts, and when a print was found in 1999, fans were ecstatic.

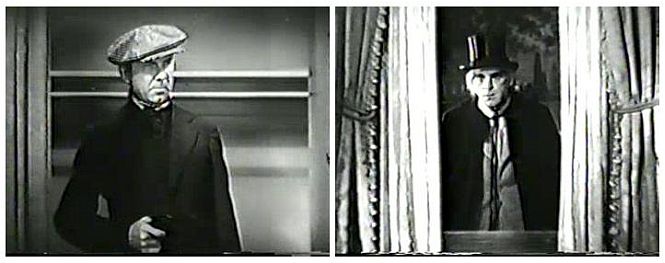

Their joy could not have lasted long, as Gift of Gab is a dire film. This comedy vehicle for Edmund Lowe concerns rakish conman Philip Gabney and his scam to make himself a radio star. Billing himself as “The Gift of Gab,” Gabney introduces a host of guest stars; in fact, the only reason to watch this thin little movie is to see musical guests such as Ethel Waters, Ruth Etting and The Beale Street Boys. Between musical acts are radio sketches, inexplicably staged as plays, complete with visual gags that could not possibly have translated to radio.

It’s in one of these sketches, a humorous murder mystery starring Chester Morris and Hugh O’Connell as dimwitted detectives, where Lugosi and Karloff appear. Lugosi is seen for less than five seconds and has one line, which is admittedly hilarious in retrospect — over sixty years of waiting to see Lugosi utter three words in a stupid skit makes Gift of Gab seem like an accidental troll. Karloff fares a bit better, but still dons Lon Chaney’s old London After Midnight getup and gets maybe 60 seconds and three lines.

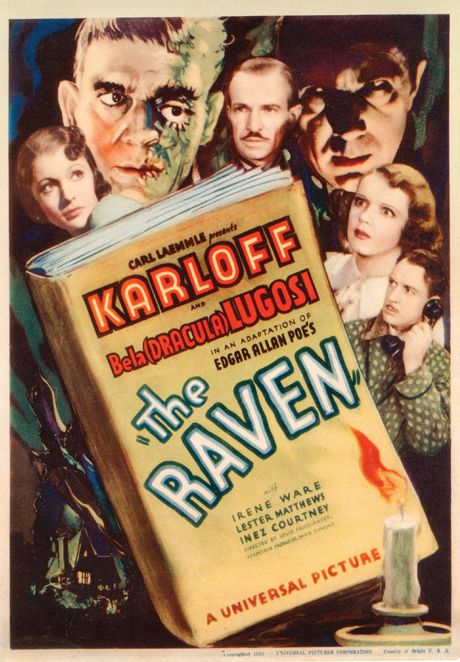

By the time The Raven (1936) was released, Karloff was unquestionably a bigger star than Lugosi, and was given first credit in the film despite being in what was actually a supporting part. Bela, as the Poe-obsessed Dr. Richard Vollin, is second billed but has a starring role. A retired neurosurgeon, he saves the life of the daughter of a well-placed senator, and falls for the beautiful woman after she recovers. When she fails to return his advances, Vollin plots to have escaped criminal Edmond Bateman (Karloff) torture and kill her father in revenge. To force Bateman into doing his nefarious deeds, he promises a facelift to help him elude police; instead, he inflicts neurological damage on Bateman, promising he will repair the damage once the senator is dead.

The two lock in a struggle of wits and wills until the rather gruesome finale, which involves traps inspired by Edgar Allan Poe stories, secret rooms, panels of delicious buttons and levers, and a cackling Bela Lugosi rattling the rafters in unhinged psychopathic glee.

The year after The Raven, the duo appeared in The Invisible Ray, helmed by long-time director Lambert Hillyer. A workhorse of a director who had been in the business 20 years by the time he was assigned The Invisible Ray, Hillyer turned in an exceptional film, garnering terrific performances from both Karloff and Lugosi. Karloff especially shines as the obsessed Dr. Rukh, giving a subtle, nuanced performance that anticipates the less stylized forms of modern day acting by a few decades. Lugosi remains understated and believable; the pair seem to have finally gotten used to each other, and their slightly skewed personal camaraderie shows in their characters, to great effect.

Long-time SBBN readers will recognize some scenes of The Invisible Ray, as they were pilfered by Universal three years later for the cinematic atrocity The Phantom Creeps. During those three years, Bela’s appearance and performance style changed drastically; he aged a decade and lost quite a bit of control of his acting abilities. The barely-tethered sexual desire and repression he so easily conjured up in the early 1930s had begun to fall apart by The Raven, where a sublime moment of unspeakable tension as he stares snakelike at his beloved becomes pastiche as his voice rises into an unnatural register, nasal and unappealing, reminiscent of Walter Matthau in the worst of his over-dyed, frenzied comedic performances. By The Phantom Creeps, very little of the well-paced stage persona of Bela Lugosi was left.

Karloff, on the other hand, improved as his career continued, so much so that many were surprised he would go back to the role of the Monster for a third and final time in the 1939 satire Son of Frankenstein. For the uninitiated, Young Frankenstein spoofs Son of Frankenstein, not the original Frankenstein as is often claimed. In Son of you’ll find Ygor (Bela), an alternately jovial and cranky assistant with a macabre sense of humor, the medically-inclined and slightly befuddled grandson of the infamous mad scientist (Basil Rathbone), and a local constable with a mechanical arm he manipulates in an awkward and hilarious way (Lionel Atwill).

Bela, in what must have been both an act of necessity and enormous bravery, takes the bad acting habits years of Z-grade shlock and personal demons have bestowed upon him and twists them into a bravura performance, one that is funny and touching and ridiculous all at once. Karloff seems less invested in his role, though is clearly enjoying himself, and both Bela and Boris are afforded the opportunity to be gruesome and frightening.

The next year, Bela and Boris appeared in Black Friday, though the pair have no scenes together. Karloff was given the role of a gangster but the director later concluded he couldn’t pull it off — which seems a bit specious, since Karloff was a fine actor and had convincingly played a gangster in Scarface — and once roles were switched, Bela was the gangster, a smaller role but with second billing. Stanley Ridges took the role of a professor with multiple personalities after an experimental brain operation, and Ridges steals the show out from both Boris and Bela.

It’s a shlocky little flick with some patently ridiculous moments, but there is a dramatic tension reminiscent of Val Lewton’s pictures of the era. A strange publicity rumor went around, stating Lugosi was hypnotized for his death scene to make it more realistic, though his death is not actually shown in the film, only reported in a newspaper.

It would be only a few months before Bela and Boris were together again, this time in the comedy vehicle You’ll Find Out, starring Kay Kyser and his band. As so many B-movie old dark house comedies tend to be, You’ll Find Out is a bit of a dud. Lugosi, Karloff and Peter Lorre appear in small parts as creepy guests in a home filled with co-eds and Kyser’s band, all stuck there until a storm passes. Murders happen, maybe, or maybe not, because this is a 1940 mystery comedy and they all rely on vague implications of horrible things happening and then just when you’re about to get scared, do something to make you realize there was never a threat at all.

The best part about the film — and I say this as someone who harbors a secret fondness for Ish Kabibble’s ridiculous “Bad Humor Man” bit — is that Lorre looks like he’s plotting to kill his agent for getting him stuck in this film, while Bela Lugosi is having a damn ball.

It would be three years before Lugosi and Karloff appeared in their final film together, the Val Lewton classic The Body Snatcher. A tight, economical production and hard-edged characters distinguish the film from other B movies of the day, and its only fault, if one has the heart to call it that, is the obvious shoehorning of the Bela Lugosi character into the plot, just to get Bela and Boris in one final film together. Karloff’s acting style was sublime in this era — his performance alone could elevate films like Isle of the Dead and The Devil Commands from useless trifles to interesting genre pieces — but Lugosi was obviously ill. Even the short cameos and small roles he had been getting were too much for him to handle, and his tiny, superfluous role as Joseph in The Body Snatcher would be one of the last real parts he had.

In their final scenes together, Karloff and Lugosi seem more like old pals than rivals, and even when Karloff, as cabman John Grey, goes in for the kill, there’s a geniality there that softens the tone, turns the murder into a metaphorical mercy killing; Grey is killing Joseph while Karloff is helping Lugosi, at least in a small way. Films often have an unseen world beyond the frame, assumptions and pasts floating around just out of the reach of the viewer, yet still informing the text of the film. For the final showdown between Karloff and Lugosi, that unseen world is not the cold streets of 1830s Edinburgh, but the harsh disinterest of Hollywood in 1945, a world consumed with reconstructing itself after a long war, one not at all interested in a middle aged drug addict who was once desired, now derided.

Stuntmen are used in the fight between Grey and Joseph, Bela often barely able to walk in the film, let alone throw a punch. Grey prevails, and we see Joseph only once more, submerged in a barrel of cold water. It’s Bela in that tank, in a stunt that must have been physically difficult for him to do, our last glimpse of him frustratingly vague, as his face reshapes while the clear water breaks in geometric patterns above him.

Bela would make less than 10 films after The Body Snatcher, many of them ultra low-budget movies by director Edward D. Wood, Jr. Karloff would go on to nearly three more decades of films, including more collaborations with Lewton, later work with Roger Corman and Peter Bogdanovich, even narrating the classic Christmas special “How the Grinch Stole Christmas.”

Together, Boris and Bela — who had two wildly disparate careers despite becoming famous at the same time, with the same studio and in the same cinematic genre — gave us a decade of terrific films. Though Boris Karloff is widely respected and beloved by today’s horror fans, there is a reverence afforded to Bela Lugosi that Karloff simply never achieved. It’s an acknowledgement of Bela’s exceptional influence in a career that was far too short, and perhaps more than a little belated love for a man whose personal struggles outdid him at a time when very few people cared. When Karloff plays a character with strength, we show respect, but when Bela’s characters have strength, we rejoice.

Sources:

The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror by David J. Skal

Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film by Harry M. Benshoff

Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting by Gregory W. Mank

Edgar G. Ulmer: Detour on Poverty Row edited by Gary Rhodes

Boris Karloff: A Critical Account of His Screen, Stage, Radio, Television by Scott Allen Nollen

The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi by Arthur Lennig

Pingback: Day Two: DYNAMIC DUOS in Classic Film blogathon | Once upon a screen...

Lovely.

Thanks!

I say this each and every time I visit SBBN – I MUST visit you more often! Simply love your writing. Fantastic post on two important figures in cinema. This is a great addition to the Dynamic Duos event!

Aurora

Thanks Aurora – and thanks for hosting!

Nicely done. One of your observations really stood out for me: “Films often have an unseen world beyond the frame, assumptions and pasts floating around just out of the reach of the viewer, yet still informing the text of the film.” Very true, and a masterful director makes the most of these. So glad you included these two in the blogathon.

Thank you, I appreciate it! I was shocked Bela and Boris weren’t taken yet, so I jumped at the opportunity. Love them both.

I was so happy to see that you were paying tribute to Boris & Bela for the Dynamic Duos blogathon. Nicely written article about their work, and I love the images you chose. I thoroughly enjoyed reading your piece! Cheers Joey

Thank you Joey, I really appreciate it!

Loved it!- hey do you have a date you’d like to post for the William Castle Blogathon?Let me know soon-thanx

Hey there – I couldn’t find a place to comment on your blog about sign up dates, so I hope responding here is okay. August 1st, the Thursday should work out the best for me. If you need it earlier to spread the articles around more evenly just let me know by early next week and that should be fine. Thanks!

I effing LOVED this entry!! Thank you SO much for posting about Karloff and Lugosi – both legends!

Thank you Vanessa! Everyone has been so kind in their comments.

This is excellent. Poor Bela. He suffered even more humiliation in his last years than Basil did. You write so well, with a real professional quality, and really know your subject. Not surprised people want to steal your stuff.

NeveR, that is a tremendous compliment, thank you.

The Body Snatcher was really the best, and the most atmospheric, in the Karloff/Lugosi pairings, and it’s said to see Bela so ill and slow in the role (though he’s professional enough to work it to his advantage, making his character someone who’s too slow-witted and simple-minded to catch on to John Grey’s nefarious dealings). The real pairing in that film is between Karloff and Henry Daniell, who gives the performance of his career as the unscrupulous doctor who hires the body snatcher and is forever haunted by him.

The Body Snatcher is one of my favorite films of all time, in part because I adore the three leads separately, and together it’s this overwhelming experience of bliss and terror that I cannot get enough of. The verbal sparring between Boris and Henry is second to none in any film, any era, any genre.

It’s curious how both are remebered for monster films, but were so different. And I feel bad because Lugosi couldn’t escape typecasting. My, she was even referred as Bela (Dracula) Lugosi in this poster for The Raven!

I enjoy The Black Cat the most, and the pairing of these two legends couldn’t have been more perfect.

Don’t forget to read my contribution to the blogathon! :)

Kisses!

It is rather ironic because Bela hated being typecast but couldn’t escape it, but Boris didn’t mind it and he had a much more varied career. Ah, Hollywood. Thanks for stopping by, Le!