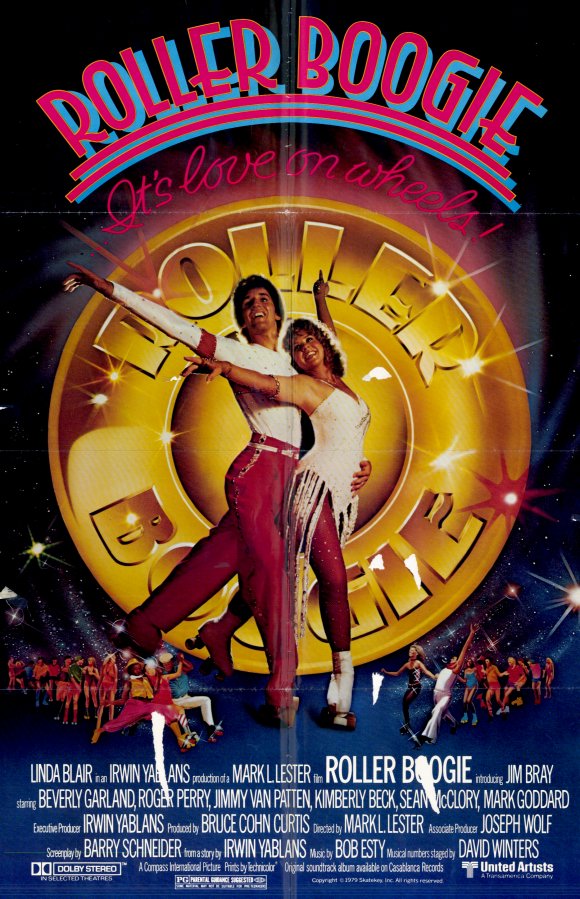

In a world where parks are full of small, evenly spaced groups of people all wearing skin-tight clothing in bright primary colors, where everyone is required by law to blow dry their hair and wear lip gloss, one recreational sport reigns supreme: roller disco. Voluptuous young Terry Barkley (Linda Blair) is a musical genius — a flautist, the sexiest of all orchestra members — but secretly yearns to become a bohemian roller skater, spending her days gliding up and down Venice Beach in Lurex leotards. There’s just one catch: she doesn’t know how to skate.

Within moments of parking her luxury car at a local teen hotspot, she catches the eye of master skater Bobby James (Jim Bray, 1970s roller skating champion). They meet, clash, flirt, clash a little more, and just as they decide they like each other, find themselves having to rescue Jammer Delaney (character great Sean McClory), the owner of the local roller rink. He’s being harassed by a gangster-shaped group of mean dudes, so the only solution, of course, is for Bobby and Terry to win the local roller skating competition.

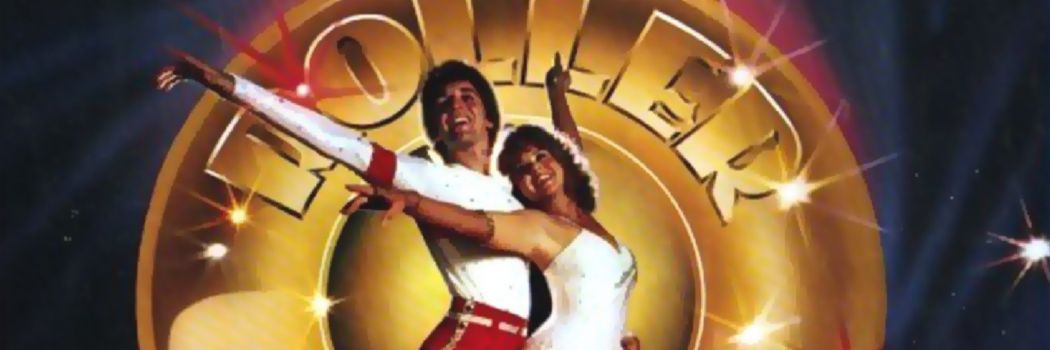

Roller Boogie (1979) is one of the most famous of the several roller disco films and shows that sprung up as the 1970s wound down. The movie was released just one month after the similar Romeo-and-Juliet-plus-skates film Skatetown, U.S.A. had bombed at the box office, though producer Irwin Yablans insisted that his film would not fail like Skatetown had. Roller Boogie would “take the world by storm,” he said. It did not. [1]

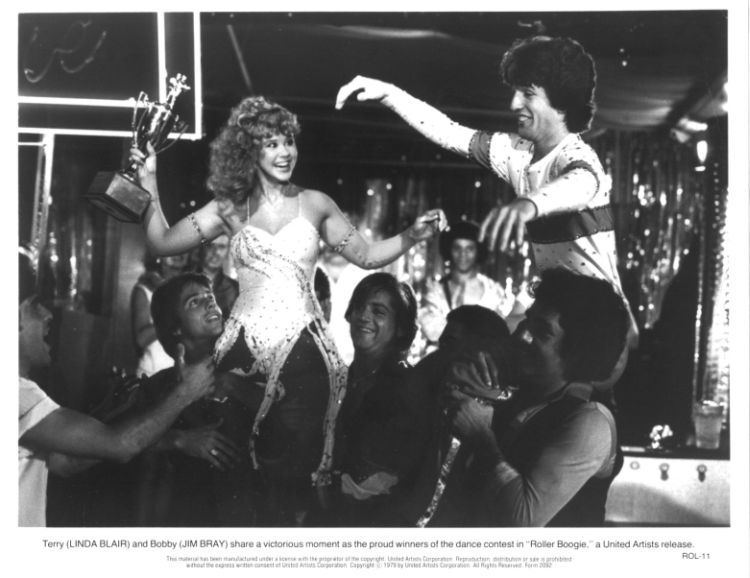

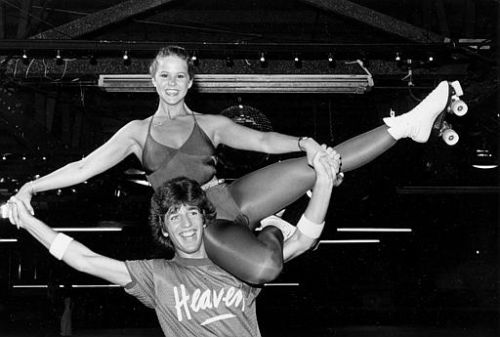

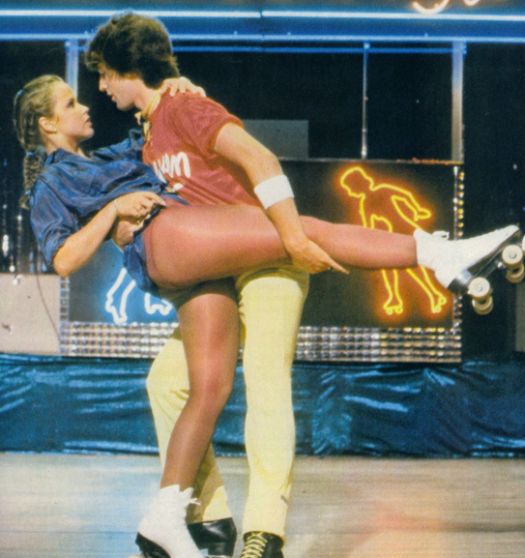

The Razzie book entry on Roller Boogie makes a snarky comment about Linda Blair’s weight in the film, saying that Jim Bray’s face shows considerable strain when he has to lift her during their routines. I think that “strain” is actually what we call “stage fright.” Compare the promotional still above during a rehearsal session to his face in the film proper below. (Pics via Susan A. Miller’s Roller Boogie clipping site, and Movieguy 24/7‘s rave review of the film).

The Razzie book entry on Roller Boogie makes a snarky comment about Linda Blair’s weight in the film, saying that Jim Bray’s face shows considerable strain when he has to lift her during their routines. I think that “strain” is actually what we call “stage fright.” Compare the promotional still above during a rehearsal session to his face in the film proper below. (Pics via Susan A. Miller’s Roller Boogie clipping site, and Movieguy 24/7‘s rave review of the film).

You would think the one-two punch of Skatetown and Roller Boogie failing would kill the roller disco craze, but you would think wrong. A month after Roller Boogie’s October release, ABC would air “Playboy’s Roller Disco and Pajama Party,” a one-hour special featuring the doomed Dorothy Stratten. In fact, the filming of this party is the event where Peter Bogdanovich first met Stratten; he can be briefly seen as a random celebrity enjoying the party. It’s a creepy and odd kind of television special, and though you may think they were all that way back in 1979, this one was worse than usual: there are old copies available online with local ABC newsbreaks still intact, where an anchorman disavows all responsibility for the show, and asks people who have turned the show off in disgust to please return for the 11:00 news.

But that didn’t kill the trend, either. Xanadu (1980), a disco movie just as fond of 1930s Hollywood tropes as Roller Boogie was, is really a roller disco movie in thin disguise. By the time Universal released Xanadu in the summer of 1980, they knew that there was no real market for roller disco films, thus tried to downplay the disco content hoping to attract audiences. It didn’t work.

Universal was just making the same sort of attempt to cash in on trends as one can see in teen films of the 1950s, when movies like Bop Girl Goes Calypso (1957) portrayed a fleeting (and, in fact, probably long-gone by the time of release) niche musical market in hopes of getting in early on the next new trend. But Hollywood doesn’t really get that whole early adoption thing, nor does it possess the nuance to understand that, though Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Grease (1978) were great films and big hits, music and dancing alone weren’t all one needed to create a popular movie.

Top: Promotional photo for Roller Boogie. Bottom: Promotional still from Prom Night (1980).

Top: Promotional photo for Roller Boogie. Bottom: Promotional still from Prom Night (1980).

Film writer Richard Nowell proposes that the same archetype for the late-teen girls in these disco films was used for horror movies of the early 1980s, and much more successfully. Perhaps not coincidentally, Irwin Yablans produced the horror classic Halloween (1978) just a year prior to producing Roller Boogie, which he considered to be his “fun” teen followup. [1]

Though Roller Boogie was an early release in comparison to most movies of this genre, the roller disco trend was already on its way out. Margo DeMello in Feet and Footwear: A Cultural Encyclopedia posits that this was due to roller blading replacing roller skating as the hot new thing. More likely, it was the decline of disco itself, and probably the infamous Disco Demolition Night held just three months earlier.

There’s been quite a bit of analysis regarding the fall of disco, and many rightly note that this “Disco Sucks” backlash objected not just to the drugs and the sex and the vapidity of the scene, but the sociocultural makeup of disco fans. Yet the stars of Roller Boogie — in fact, the entire world these Southern California teens live in — are all white, and either enormously well-off or poor in that noble Hollywood way that indicates that, in a few years, they’ll be rich and successful, too.

In short, Roller Boogie is disco scrubbed clean of its counterculture bona fides, bleached and filtered into something where the only real danger that exists is that you might fall into a swimming pool on a hot summer day, or your parents might turn out to be jerks. There is no emotion to be had here, either, despite this being a romance. Everything is kept tepid and implied, friendly and jovial, with easy answers to even easier questions providing the only thing that even comes close to conflict.

Though the outer appearance of disco in Roller Boogie has been molded into something decidedly bland, the film’s shallowness, somewhat ironically, represents disco in its most pure, undiluted form. As music critic Lester Bangs wrote in “On the Merits of Sexual Repression:”

In the last few years we have seen the rise of a type of music perhaps previously unknown in human history: music designed specifically, by intent or subconscious motivation, to remove what emotions might linger in the atmosphere around us, creating a vacuum where we can breathe easier because we’re not so freaked by each other even though we still don’t communicate. That’s your basic disco, of course.

Bangs is talking more about Blondie and Roxy Music here, specifically their studied nonchalance and heavy ironies, but “your basic disco” also qualifies. It’s music that wants nothing more than to create a blank slate for those ultra-cool moments when music is necessary, but the emotions it stirs up are inconvenient. With disco, you can roller skate and dance and snort a few lines while saving your concentration on more important things: looking fabulous and, of course, bored.

Roller Boogie features watered-down, teenaged versions of the cocaine- and sex-fueled nightlife scene, and thus does more than any sociocultural analysis could to point out the inherent emptiness of it all. Not the ironic emptiness scenesters thought they were embracing in the late 1970s, but the real, actual, genuine emptiness, the fact that, far too often, the adult world was really just Barbie dresses and Hot Wheels and glitter paint, plus nosebleeds and herpes.

Promotional still courtesy Susan A. Miller’s fantastic Roller Boogie website.

Promotional still courtesy Susan A. Miller’s fantastic Roller Boogie website.

Roller Boogie is, of course, unintentionally hilarious, which long-time SBBN readers will remember is the best kind of hilarious. The usual B-movie problems are all here, from rotten dialogue to basic plot issues to outsized comedic antics passed off as normal behavior. Unlike a lot of B-movies released from roughly the late 1970s through the 1980s, however, the homoeroticism here is truly accidental — the filmmakers wanted bland and vanilla teen disco, remember, not reality — so of course, it’s great fun to watch.

Take for example Bobby’s sad, skated lament over the possible loss of the roller rink. Clad in a skin-tight tee adorned with the letters “BJ” in glitter font, he swoons in slo-mo tribute to the drunk and despondent Jammer, as a tepid cover of Supertramp’s “Lord is it Mine” plays:

It’s so bad it doesn’t even rise to the status of emotional simulacrum, but it’s campy as hell, and thus is what they call “worthwhile.”

In 1988, Jack Barth, writing an (ahem) “Ultra-Poignant Ninth-Anniversary Commemorative Celebration” of the film for Spy Magazine, said the day Roller Boogie was released was “the day the Seventies ended.” That’s not precisely true, as the Seventies were winding to a close months earlier. Our memories trick us into believing 1979 was full of Brenda Ann “Mondays” Spencers and swamp rabbits, when in fact the first half of the year saw improved diplomatic relations with China, the completion of the first Space Shuttle, and the riots after the Harvey Milk-George Moscone verdicts. By the time October rolled around, the world was a different place than it had been when Roller Boogie went into production.

That same 1988 Spy Magazine article mentioned that an unnamed MGM/UA executive had labeled the film “unwatchable.” The studio refused to allow its release on home video, though they had tried to unload it on small video distribution companies, but, “they don’t want it,” said the executive. “Nobody wants it.”

It may have taken over 25 years, but the world has finally proven him wrong. Roller Boogie has been released by Olive Films on DVD and Blu-ray, in what is a really nice-looking print. It’s a bare bones MOD Blu-ray with chapter options only, and no subtitles. The sound in particular is very good, and with a soundtrack that is occasionally stellar — “Boogie Wonderland” and Cher’s “Hell on Wheels” in particular — that’s important.

Roller Boogie may not be particularly complicated, but the era it comes from most certainly is. Wrapped in the guise of escapist entertainment, the film is a unique historical document of a time when emotional connection to art was not only difficult to maintain, but actively avoided. Roller Boogie is candy-colored and sparkly and contains about as many deep thoughts as a Bazooka bubble gum wrapper, but it’s also a time capsule to an era that came and went so quickly we still don’t know what to make of it.

–

[1] Blood Money: A History of the First Teen Slasher Film Cycle by Richard Nowell

It seems fitting that no less a film than Heaven’s Gate has what can fairly be described, spiritually if not musically, as a roller disco scene. I can’t help feeling it was there for a reason beyond anyone’s commitment to local color or authentic period entertainment. But who can say?

Argh, I still haven’t watched that copy of Heaven’s Gate that I bought nearly two years ago.

In one of the books I read about this movie, someone noted that Universal considered Xanadu to be their light & frothy summer hit, something to pair with their serious & intense Heaven’s Gate. Oy.

I have to think that Hollywood execs were just obsessed with scoring another Saturday Night Fever and all their good sense was thrown out the window, then replaced with greed.