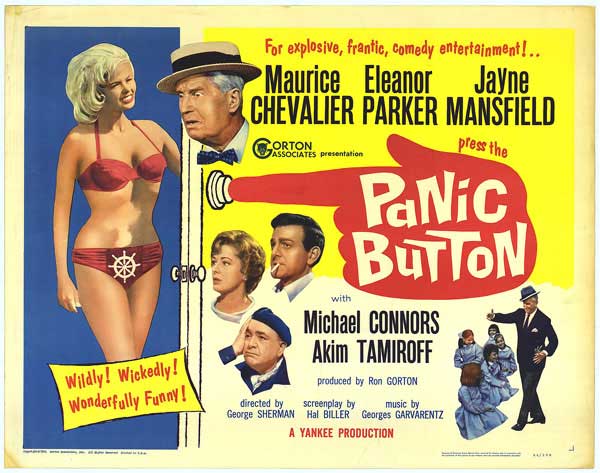

When a Hollywood production company discovers they have a half million dollars in unclaimed profit they have to lose to avoid prosecution by the Feds, they come up with a wacky scheme: to film a truly awful television pilot so bad it guarantees a loss. The president of the company sends his son Frank (Mike “Touch” Connors) to Italy to put the deal together. Frank quickly convinces elderly, washed-up actor Philippe Fontaine (Maurice Chevalier) and his beautiful ex-wife and manager Louise (Eleanor Parker) that this new modern production of Romeo and Juliet will be a great comeback opportunity for the former star. Add the buxom Angela (Jayne Mansfield), a gorgeous local prostitute with a heart of gold, as Juliet and one truly terrible director known as Pandowski (a wonderful Akin Tamiroff) to the mix and you have a recipe for disaster — just what Hollywood ordered.

Panic Button, recently released for the first time on DVD through Warner Archive’s made-on-demand series, is a surprisingly pleasant spoof of the early 1960s trend toward lavish Hollywood productions in Italy. There are elements of a sex farce here — Louise runs a hotel for women, Frank likes the ladies, and Angela’s vocation is meant to raise eyebrows — but mostly, Panic Button is a light romantic comedy. Parker looks absolutely stunning and gives the kind of performance that, had everyone else involved been so dedicated, would have prevented Panic Button from becoming basically forgotten. Chevalier is charming and has a couple of musical numbers of little consequence, and Mansfield, despite the publicity for this film, is far more clothed than you would really expect.

Philippe makes ends meet by performing on the street as a cautionary tale against drunk driving.

Philippe makes ends meet by performing on the street as a cautionary tale against drunk driving.

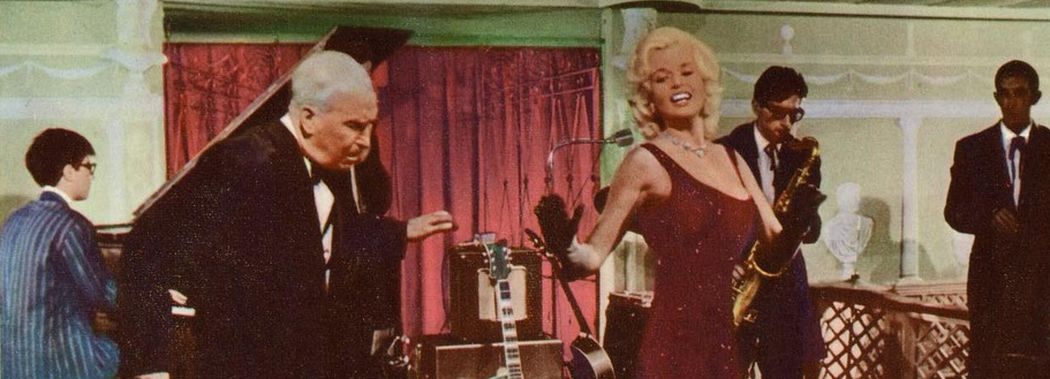

Panic Button is noted, when it’s noted at all, for one specific scene of Maurice Chevalier and Jayne Mansfield doing The Twist at a nightclub. But here’s the thing (and, not incidentally, the reason why it took so long for me to write this film up): the Twist scene does not appear in the recently released Warner Archive version of the film.

But that’s okay, because a generous soul has uploaded it to YouTube:

There are some (if you’ll pardon the mention of such a thing) bootlegs of Panic Button out there that specifically advertise this scene, and the scant references of the movie in books and old publicity make quite a bit of it, as well. In the video above, you can see the last seconds of a slow dance that ends just before the faster dance music. In the Warner Archive print, there’s a clear edit at that point, and it’s a different camera angle (or take) than the Italian footage above. Warner Archive was kind enough to confirm that this print of Panic Button comes from new elements — and the print does indeed look lovely — but I don’t think this means the scene was somehow forgotten. Rather, I think the Twist only appeared in the Italian version of the film, or maybe just in the promotional footage and trailers, because it’s pretty rough footage. Mansfield spends a lot of time looking straight at the camera, going way off her marks, and at a few points looks as though she’s about to completely lose it physically, perhaps even emotionally.

That the Twist was such a talking point for Panic Button during filming but then didn’t even end up in the release isn’t surprising: the publicity of Panic Button was a hell of a mess. Producer Ron Gorton got the idea to release scandalous tidbits during filming, hoping to engender the same kind of attention that Cleopatra (1963) had during its tumultuous production. Meanwhile, Jayne Mansfield was also desperate for publicity in the months leading up to Panic Button. On her way to announce it as her next film, she, her husband Mickey Hargitay and a promotions agent were “lost at sea” for a day. A few months later, she filed for divorce because Hargitay had allegedly forbidden her to take their children with her to Italy during filming. Eventually, he agreed to go with her and bring the children along, and she dropped the suit.

Then there were what we now call wardrobe malfunctions — two in one night, if you can believe it. Her breasts fell out of her dress the first time at a pre-production party with cast and crew; the second time, at a night club where she was, depending on who you ask, either too drunk or trying too hard to get the attention of production manager Enrico Bomba. Another incident involving her troublesome wardrobe happened as she filmed the Twist scene, and several recollections of that night suggest Jayne was drunk and angry, having just discovered she was let go from 20th Century-Fox. Maurice Chevalier, recounting the incident to Variety, noted with some distaste that not only was the whole thing far too demanding for an actor of his age, but Mansfield lost her bra during her dance.

Louise rolls her eyes at Philippe so hard it’s a wonder her face doesn’t freeze that way.

Louise rolls her eyes at Philippe so hard it’s a wonder her face doesn’t freeze that way.

Variety reported quite a bit about the filming of Panic Button, in fact, and none of it good, thanks to Ron Gorton feeding them stories. He claimed Eleanor Parker was a no-show for the first several days, and reports of her fighting with Gorton kept surfacing. But that wasn’t the end of the seedy publicity: Mansfield was reportedly injured several times, not during filming but rather being hit (by whom, no two stories agree) or taking a fall after too much drink. After filming ended, Mansfield actually called a press conference in September of 1962 to explain away her newest injuries with a whopper of a story about a melee at the Silver Mask Award ceremony. She was obviously trying to emulate the publicity Elizabeth Taylor received the year prior when a near riot broke out as she attended the same awards, but there’s likely something else more sinister going on there, too.

But the bad luck doesn’t stop there! After laying around on the shelf for a year, Warner Bros. decided against releasing Panic Button, deeming it unsuitable and unprofitable — if you’re wondering why Panic Button is listed in various sources as being released in 1962, 1963 and/or 1964, that’s why. Gorton sued Warner Bros. and won the right to release it himself, and indeed, throughout the fall of 1963, trade papers featured small articles fed to them by Gorton regarding financing opportunities for investors wishing to help him release the film. Finally, in April of 1964, Panic Button showed in a few theaters in New York City and Los Angeles, receiving mediocre reviews, though Film Daily thought highly of it.

And then, it disappeared, only to be seen by a few who happened to stumble across iffy VHS copies or nasty prints on the local late-late show.

Much has been made of the similarity in plots between Panic Button and Mel Brooks’ The Producers (1967), though it should be noted that another recent Warner Archive MOD DVD release, New Faces of 1937, features a young Milton Berle concocting a scheme to oversell shares of a guaranteed flop. This is an idea that has been around for a long time.

That said, the character of Pandowski is shockingly similar to Roger De Bris (Christopher Hewett in The Producers), and the reception that the ridiculous Romeo and Juliet receives is so comparable to the audience’s reaction to “Springtime for Hitler” that it’s very tempting to consider Panic Button a likely inspiration for The Producers, albeit one of many.

Thanks to my good pal Matt on Facebook asking questions, I started digging a little further into this whole influence thing, and uncovered quite a bit about the origin of this particular plot. It seems that the film New Faces of 1937, mentioned above, was based on a short story called “Shoestring” by George Bradshaw, published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1933. That seems to be the origin of the production scam story — Mondo 70 has a really great write-up of New Faces of 1937 with more details about this, by the way.

The RKO “New Faces” revues ran from 1934 to 1968, with New Faces of 1937, the one based on “Shoestring,” being just one installment of the series. The 1954 revue, titled simply New Faces, featured none other than Mel Brooks as a writer. It was probably the New Faces of 1937 story that influenced The Producers more than Panic Button; it seems more likely that Brooks saw that film (or read the script) than it does for him to have caught Panic Button one of the few times it was shown in a theater.

Convincing Pandowski to take the job.

Convincing Pandowski to take the job.

The back half of Panic Button turns into one of those wacky comedies that has no idea what it’s doing with itself, and therefore winds up with men disguised as nuns and scenes of Jayne in a swimsuit just so they can shoehorn a little cheesecake in there. It’s not meant to be serious, but it’s also not always successful at being funny, either. There’s a palpable strain on everyone involved, and one can’t help but assume all the shenanigans and drama were taking a toll on the cast and crew. But it’s still a pleasant film, one that comes at key times in nearly all the leads’ careers, and a really interesting slice of low-budget fare from an era in transition.

Panic Button is available on MOD DVD from Warner Archive.

Sources:

Fifties Blondes: Sexbombs, Sirens, Bad Girls and Teen Queens by Richard Koper

Eleanor Parker: Woman of a Thousand Faces by Doug McClelland

Chevalier: The Films and Career of Maurice Chevalier by Gene Ringgold and DeWitt Bodeen

Jayne Mansfield: A Bio-bibliography by Jocelyn Faris