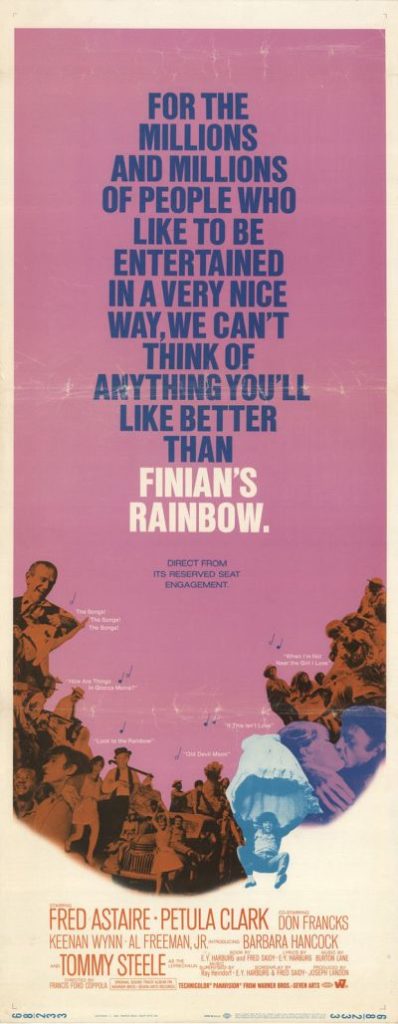

Finian’s Rainbow (1968), a politically themed musical based on a 20-year-old Broadway hit was, somehow, Francis Ford Coppola’s first major motion picture. Starring Fred Astaire as Finian McLonergan and Petula Clark as his daughter Sharon, Finian’s Rainbow features songs that, by 1968, were favorite standards. The film follows the pair as they trek across the United States in search of Rainbow Valley in the fictitious state of Missitucky. Finian has a grand plan: to plant a pot of gold in a valley near Fort Knox, believing that doing so will result in more gold sprouting from the ground. The only problem is that Finian has stolen the gold from Og (Tommy Steele), a leprechaun who has followed him to Rainbow Valley, desperate for the gold back. The gold keeps Og a leprechaun; without it, he starts to slowly turn human. Worse yet, gold turns to dross after three wishes, and if they aren’t careful, people nearby will accidentally use up the gold and doom Og to a life of humanity.

Meanwhile, in the idyllic Rainbow Valley, race relations are becoming strained. Racist senator Billboard Rawkins (Keenan Wynn) is hassling the people, while whitebread but well-meaning activist Woody Mahoney (Don Francks in an unconvincing wig, which SBBN will always contend is the best kind of wig) tries to protect them. Sharon falls for Woody; she also become enraged at Senator Rawkins’ racism, and without realizing a pot o’ gold is nearby, wishes him black so he can learn a valuable lesson. Shenanigans, as they say, ensue.

Finian’s Rainbow is stagey, self-consciously so, which helps remind the audience that what we’re watching is allegory and spoof, lest anyone get the radical idea that gender, economic and racial equality were something meant for the real world. It’s a bit surprising that this play originated in 1947, since its decidedly left-leaning politics fit so nicely into the zeitgeist of 1968 Middle America; actual leftists had long since moved on, as Coppola later said: “A lot of liberal people were going to feel it was old pap.”[*]

A few changes from the 1947 script were necessary by 1968, though, namely that, as the producer of the aborted 1953 animated version of Finian’s Rainbow said, the film “tells you that a terrible person turns black because he’s so bad, and then redeems himself and they reward him by making him white again.”

Not everything that should have been updated was, however. The senator still turns black, which in this case means putting Keenan Wynn in truly terrible blackface which rubs off when touched, and stays rubbed off for minutes on end because Coppola wanted long takes. Then there’s Howard, the black botanist-turned-butler who is working on a revolutionary new invention: crossing mint plants with tobacco plants to create pre-mentholated tobacco.

During the HUAC era, Finian’s Rainbow was very clearly touting a socialist message, yet the play was an enormous success. Maybe it was in spite of the HUAC era, maybe it was because of the HUAC era, but the original Broadway production won three Tony awards and ran for 725 performances.

Though maybe it wasn’t as easily successful as its run on Broadway makes it seem. When the 1953 animated version, to be directed by HUAC victim John Hubley, was in production, funding was difficult to get. There’s a fantastic essay here at Michael Sporn’s site about the animated film that never came to be, which also includes recently unearthed storyboards. At some point Frank Sinatra learned of the project and was “wildly excited” about it, and eager to sign on as a voice actor and singer. Then Ella Fitzgerald signed on, Nelson Riddle agreed to orchestrate, and everyone else followed, happy to work with some of the biggest names in the music business. (Sinatra’s recordings from the production are available on a 2002 box set. In 1963 he, Fitzgerald, and several Rat Pack pals took on the entire soundtrack for Frank’s Reprise Records.)

Tommy Steele as Og, the beleaguered leprechaun, is… shrill and melodramatic, to put it kindly.

Tommy Steele as Og, the beleaguered leprechaun, is… shrill and melodramatic, to put it kindly.

The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees was very pro-HUAC at the time, and when they learned of Hubley’s involvement in the project, they hit the roof. Hubley had been ducking HUAC for a long time after quitting Disney in 1941 during the famous animators’ strike and IATSE, the union that basically controlled all the animation studios in Hollywood, wanted Hubley to testify to “clear his name,” which of course really meant “to name names.” He refused, too many people distanced themselves from him, and the project fell apart.

If I talk a lot about this film that was never made, it’s because the live-action 1968 version will always live in the shadow of the phantom 1953 animated version that was thwarted by political extremism. But with such a political work of art, albeit American politics coated in a thick glossy layer of fantasy and confused quasi-Irish myth, you’re going to get some backlash, even in 1968. Coppola acknowledged liberals would think it was “old pap,” but he also knew conservatives would think it was “nonsense,” and he’d end up getting it from both sides.[*] Thus he re-wrote the script, updating it for 1968 audiences and at times toning down the “liberal nonsense” to family-friendly degrees.

The results were mixed. Choreographer Hermes Pan was frustrated with having to work with the soft, mushy forest set left over from Camelot (1967), but Coppola blamed Pan for the problems, fired him, then choreographed the rest of the film himself, where “choreograph” means “Coppola told dancers to ‘move with the music’ and little else.”[*] As delightful as Finian’s Rainbow is, and as professional and accomplished as Astaire is, you can tell the difference between the Pan scenes and the Coppola scenes.

Renata Adler, who was always obsessed with the physical appearances of movie stars, had some rather nitpicky complaints, but her observation that Fred’s feet go missing during several dancing scenes is sadly accurate, the result of poor studio cropping for a roadshow version of the film. It was such a shocking mistake that it practically galvanized a nation at the time. But she also groused about Astaire looking old, as though that were a technical issue on par with bad dubbing and a clumsy crop. In turn, Roger Ebert complained about Adler’s complaining. Behold the heady world of film criticism, my friends.

Pulp Fiction (1994)

Pulp Fiction (1994)

Dir: Quentin Tarantino

Finian’s Rainbow wasn’t a box office smash, but it did bring in about $2M in profit [*] and help establish Francis Ford Coppola as a legitimate director; Coppola would also meet George Lucas, a Warner Bros. intern, during the making of the film. It would be Fred Astaire’s final musical, and thoroughly fail to launch the film careers of either Petula Clark or Tommy Steele. But it’s a fun film, it really is family friendly, the songs are unabashed standards, and it’s part of Hollywood history.

Finian’s Rainbow has been release by Warner Archive on a made-on-demand Blu-ray that includes the roadshow version (with overture, entr’acte, and exit music), introduction and commentary with director Francis Ford Coppola, theatrical trailer, and the made-for-TV featurette of the world premiere of the film.

—

[*] Godfather: The Intimate Francis Ford Coppola, by Gene D. Phillips