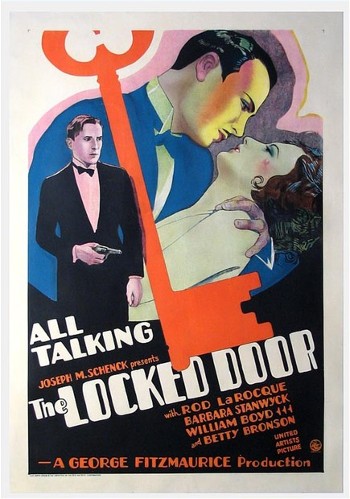

“The Locked Door” is an early talkie and one of Barbara Stanwyck’s first film roles. The story was originally a stage play called “The Sign on the Door”, a melodrama by Channing Pollock that ran from 1919-1920 and which garnered very good reviews. It was spiced up for film by C. Gardner Sullivan, who added a little Prohibition twist to the plot.

“The Locked Door” is an early talkie and one of Barbara Stanwyck’s first film roles. The story was originally a stage play called “The Sign on the Door”, a melodrama by Channing Pollock that ran from 1919-1920 and which garnered very good reviews. It was spiced up for film by C. Gardner Sullivan, who added a little Prohibition twist to the plot.

“The Locked Door” was received relatively well yet usually compared disfavorably to the stage play. Dick Hunt in the Los Angeles Evening Herald wrote the plot was “a bit commonplace at this day and age”, and that it was a formula which had “been used again and again and the present version takes very few steps toward changes.” Film Daily in 1930 noted that while the stage play had been gripping: “its talker form, though dulled somewhat by the stream of similar stories…still makes the grade as effective entertainment…largely due to a slight modernization plus the efficient directorial efforts of George Fitzmaurice and the very acceptable cast.”

That very acceptable cast, of course, was Barbara Stanwyck, Rod La Rocque, William “Stage” Boyd, and Betty Bronson. And we should probably clear up the confusion about William “Stage” Boyd before we go any further:

Larry is played by William “Stage” Boyd, not the same actor as William Boyd of Hopalong Cassidy fame. Sometime around 1929, probably after filming for “The Locked Door”, William Boyd was signed to RKO the day William “Stage” Boyd hit the papers for possession of pornography, gambling equipment and alcohol (during Prohibition), causing the innocent William Boyd to lose his contract with RKO when he was mistaken for William “Stage” Boyd. The Boyd in “The Locked Door” still goes without the “Stage” in his screen name, but by 1930 the confusion between the two actors caused the porn ‘n’ gambling Boyd to take William “Stage” Boyd while the other actor was credited as William “Bill” Boyd.

There are contradicting stories about how William “Stage” Boyd came to his nickname; some say he was legally forced to when William Boyd took him to court, while others say he did it to show he was better than the other William Boyd because he had stage experience. Either way, it’s clear that William Boyd had been in more films and was relatively well known by the time William “Stage” Boyd began to have success in film. William “Stage” Boyd died in 1935 from alcohol and drug-related illnesses — he basically spent too many years being William “Stage” Boyd — and whether it was cause and effect or not, after his death the other William Boyd’s career started to flourish.

There are contradicting stories about how William “Stage” Boyd came to his nickname; some say he was legally forced to when William Boyd took him to court, while others say he did it to show he was better than the other William Boyd because he had stage experience. Either way, it’s clear that William Boyd had been in more films and was relatively well known by the time William “Stage” Boyd began to have success in film. William “Stage” Boyd died in 1935 from alcohol and drug-related illnesses — he basically spent too many years being William “Stage” Boyd — and whether it was cause and effect or not, after his death the other William Boyd’s career started to flourish.

William “Stage” Boyd isn’t a bad actor here, but he looks far older than his years and slurs many of his words in his first scene. While others in the film are often singled out in contemporary reviews for their good performances, the only good notice I can find that mentions Boyd is a comment in the L.A. Examiner which calls Stanwyck “excellent” and incidentally mentions Boyd is as well, almost as an afterthought.

Wow, we’re taking longer and longer to get to the actual film in these posts, aren’t we? Enough dawdling about porn and drugs, let’s get on with the show.

Wow, we’re taking longer and longer to get to the actual film in these posts, aren’t we? Enough dawdling about porn and drugs, let’s get on with the show.

This movie promised art deco heaven, and it delivered. Just look at that title card! Frank’s apartment later on is stunning as well. Thank you, William Cameron Menzies. There’s nothing better than the sets of an early talkie, all crazy diagonals and streamlined symmetry. Beautiful.

The scene is set with not-so-special effects that include an obvious model boat, and then an obvious boat facade in an obvious faux ocean. Frank (Rod La Rocque) and Ann (Barbara Stanwyck) arrive on the party boat and make with the camera-conscious small talk. Wow, Rod La Rocque! I always shout his name when I see him, and I don’t really know why. I recently saw him in a very small part in 1939’s “Hunchback of Notre Dame.” His career really seemed to fade after talkies came in and he went free agent in 1928.

But this time I let out another wow: “Wow, what stiff acting!” The pacing is off, Rod and Barbara speak far too slowly, their nods and laughs are seriously fake. La Rocque is constantly glancing off screen — to cue cards, I assume, or maybe out of self-consciousness — and tries to pronounce high-falutin’ words like “n’est ce pas” and “caviar” with little success. Yet, he received pretty good reviews for the film. Kenneth R. Porter in The Los Angeles Examiner said, “It is a triumph for Rod La Rocque. He is, in the mind of this reviewer, seen in his most powerful role as a suave young millionaire whose practice it is to play on the hearts of women. His mild manners and speech is matched by none in such portrayals.”

Not everyone agreed with Porter, as the next year when La Rocque starred in the hit “The Delightful Rogue”, reviewer Jerry Hoffman stated that La Rocque hadn’t “been seen in as good a role for himself in a long time”. Hoffman also notes that La Rocque, even in the well-received “Delightful Rogue” had a very poor accent, yet it was “not worth bickering over.”

As the camera pans over the crowded bar, the dialogue is almost impossible to hear except for the “I wanna drink!” lady. The basic point is that tons of people want tons of drinks. We learn that Ann is Frank’s father’s secretary. He has reserved a little private room for dinner, where a very dim waiter — Harry Stubbs, Buck Bachman from “Alibi” — waits on them to alleged comedic hijinks. These hijinks consist of a lot of “yes, sirs”. When Comedy Waiter leaves, Frank hits on Ann, the young girl fresh from Dayton at her first wild party, in a decidedly inappropriate way. She doesn’t mind at first, but then he tries to get her drunk and feel her up. She tries to leave but he locks the door to keep her in the room against her will and attempts to rape her.

As the camera pans over the crowded bar, the dialogue is almost impossible to hear except for the “I wanna drink!” lady. The basic point is that tons of people want tons of drinks. We learn that Ann is Frank’s father’s secretary. He has reserved a little private room for dinner, where a very dim waiter — Harry Stubbs, Buck Bachman from “Alibi” — waits on them to alleged comedic hijinks. These hijinks consist of a lot of “yes, sirs”. When Comedy Waiter leaves, Frank hits on Ann, the young girl fresh from Dayton at her first wild party, in a decidedly inappropriate way. She doesn’t mind at first, but then he tries to get her drunk and feel her up. She tries to leave but he locks the door to keep her in the room against her will and attempts to rape her.

At the same time a bajillion cops are alerted that this ship, which had been 12 miles out to sea and therefore beyond the jurisdiction of the U.S. Prohibition laws, has entered into American waters and is now breaking the law. The bajillion cops pile into two small speedboats and head for the yacht party to bust up the revelry. They show up just in time to distract Frank from his attempted rape. Frank convinces Ann to keep mum, passing them off as Mr and Mrs Joe Smith and paying off a photographer to keep their picture out of the paper.

Larry Reagan (William “Stage” Boyd) is at home with his wife of just one year, Ann, and his little sister Helen (Betty Bronson). Larry and Helen have one of those weird pre-code family relationships where brothers and sisters — or fathers and daughters in the case of “Tarzan” — act almost as if they’re married. Ew.

Larry gives his wife and his sister romantic jewelry gifts for his first wedding anniversary. See? Why does the sister get a romantic jewelry gift because it’s her own brother’s one-year anniversary? Bleah.

While they coo over their necklaces, Larry discovers his friend John Dixon is coming home early from an overseas trip. Dixon has heard his wife is cheating on him and he’s angry enough to kill.

While Larry worries about his friend, Helen’s boyfriend arrives, and of course it’s Frank. Ann is upset to see Frank again because she knows what kind of man he is, and in a moment alone he orders her to keep quiet or else he’ll tell Larry about the yacht party raid… and that she and Frank skipped bail after their arrest. Oops.

Larry is upset to see Frank for other reasons — Frank is the guy who has been diddling Dixon’s wife. Neither want Helen to continue to see Frank, but she is stubborn. Frank has secretly yet falsely promised her marriage if she will travel to Honolulu with him the next morning. After Ann orders Frank to leave, Larry tells Ann that he’s afraid she and Frank have a sordid past together. Ann teases him about being jealous, but Larry is deadly serious: he could never forgive Ann if he found out she and a scumsack like Frank had been lovers.

Larry takes an urgent call where he is told his friend John Dixon is heading out to kill himself a big ol’ scumsack. Larry immediately leaves to stop Dixon, and moments later Ann discovers Helen has sneaked out and gone with Frank.And this is kind of an odd note, but the roads we see Frank drive on after he leaves the house look exactly like roads I’ve seen in old 1950s promotional reels with actors doing “candid” things; I swear that within the last few weeks I saw one of these promotional shorts with Jack Lemmon driving the exact same roads Frank is on now. Just… you know, you watch a few thousand movies and shorts, you start to notice goofy things like that.

Back at Frank’s fabulously appointed art deco apartment, Frank crudely tells his butler Ferguson of his plans to seduce the virgin Helen. Ferguson joins in on the plot, helping with a “Do Not Disturb” sign and purchasing tickets so Frank can spirit a kidnapped Helen away to Havana (instead of the promised Hawaii) unawares. Ferguson also makes sure Frank has a gun nearby in case Dixon shows up.

Dixon never does. Instead, Ann arrives to stop Frank from ruining Helen, but he blackmails her with the photo the news photographer took the night of the yacht party raid. Just then Larry knocks on the door. Ann hides while Larry enters and immediately threatens Frank. Frank pulls a gun on Larry and, for whatever reason, lies and tells him Ann used to be his lover. I guess he did it because he’s a scumsack, and that’s what scumsacks do. A scuffle ensues and the gun goes off. We don’t see the struggle between the men but we see the aftermath: Larry holding the gun over Frank’s dead body. Larry cleans up the scene, hangs up that “Do Not Disturb” sign as he leaves, and locks the door behind him, trapping Ann inside.

Another locked door! Ann has no key and cannot escape. In desperation to get out of the apartment and to save her husband from a murder charge, she takes the phone off the hook so the hotel operator (ZaSu Pitts in the allegedly comic role of the film) overhears a faked scuffle. Ann screams, rips her own dress, and fires shots.  When the police and landlord arrive she falsely confesses that she killed Frank in self-defense. She’s forced to sit around with her dress ripped off half her bosom because it’s “evidence” for the D.A. As she waits to be questioned, the D.A. finds part of the photograph of her and Frank at the yacht raid, but the top part of the photo with their faces is missing. Ann has that part hidden in her dress.

When the police and landlord arrive she falsely confesses that she killed Frank in self-defense. She’s forced to sit around with her dress ripped off half her bosom because it’s “evidence” for the D.A. As she waits to be questioned, the D.A. finds part of the photograph of her and Frank at the yacht raid, but the top part of the photo with their faces is missing. Ann has that part hidden in her dress.

Meanwhile the telephone girl remembers that Larry Reagan wanted to see Frank that night, too, so the police send for him. As they wait the police find Ann’s purse and discover she is Larry’s wife, which changes things considerably.

During questioning, Ann says she was there to protect another woman she refuses to name, but she stands by the story that Frank attacked her so she shot him in self-defense. The D.A. quickly points out that she cannot account for the Do Not Disturb sign, plus she says she only shot twice yet 3 shots were fired.

When Larry arrives, the police stash her in the room with Frank’s body while Larry is brought in and questioned. Nice.

The D.A. condescendingly questions Larry and, when done, tells him to go into the room where Frank and Ann are but doesn’t tell him why. As Larry and the D.A. enter the room, the D.A. announces Frank Devereaux is in the room, but isn’t actually dead. What? The dude’s not dead?! He’s been lying in a river of his own blood for something like 3 hours now. Also, Ann was in there with him for several minutes and didn’t know? Good grief.

Ann — thoroughly freaked out by now — reveals the pieces of the photo that prove she and Frank skipped bail. She won’t, however, reveal the name of the person she’s protecting. She insists she was never Frank’s lover but Larry doesn’t believe her. That is, he doesn’t believe her until the police officer with the D.A. confirms her story. The officer was the rotten waiter on the yacht that night, working undercover as part of the raid. Sigh.

So the plot is completely out of hand at this point, but Stanwyck is, by contrast, pretty good in this film. She was praised by many critics as being natural in front of the camera and not having a problem with transitioning to talkies. Louella Parsons said after Stanwyck’s next film, “Ladies of Leisure”, that the two films “did the trick” and made her highly sought after in Hollywood. Just after “Ladies of Leisure” Harry Cohn signed her to an exclusive 4-picture-per-year deal with a clause stating she had to be the star of all her films.

Moments of Stanwyck’s brilliance show when she teases Larry about being jealous, when she breaks down during interrogation, and when she tells Larry she can’t divulge who the other woman she’s protecting is. Stanwyck apparently was not proud of her performance here, and while she stumbles quite a few times, she’s certainly not the worst actor of the lot. I think it’s cute that Stanwyck in 1929 already had the habit of looking at the foreheads of other actors when interacting closely with them. It’s quite noticeable when an actor can’t or won’t look at their co-stars’ eyes, but at least she doesn’t do the back and forth flitting about that a lot of actors do when they’re unable to look at another.

If Stanwyck was good in this film, Betty Bronson was even better. She knew her way around a talking movie and was simply exuberant. The film was obviously a creaky old stage play and most characters didn’t diverge from that, but Bronson did. She took the nearly-useless role of Helen and made her a cute little flapper, very modern and very relatable, which really added to the film.

When Larry realizes Ann wasn’t the harlot he suspected her of being, he tries to confess to the crime, but no one believes him. Even though he did it. Just then the operator girl announces that a woman wants to come upstairs to see Frank, so they all hide and wait to see who it is. Of course it’s Helen, who when confronted says she was coming to tell Frank she decided not to run off with him.

Everyone goes back into the room where the maybe-dead-maybe-not Frank is laying bed, and Frank does the one good thing he’s ever done in his life. Or something. Reviewer Dick Hunt wrote, “So that things will not become more complicated, the dying villain obligingly regains consciousness long enough to exonerate all, explaining that it was an accident, which eliminates a long and tedious courtroom sequence.” Yeah, apparently. Sheesh.

Technically this film is quite competent for the early era. The sound is nice, the camera work isn’t too static, and of course the sets are beautiful. The acting side of the film suffers because of the new technology, though, and I never know how to judge a film like this. There is only so much I can forgive because of the technology. For example, the performances were problematic, but at the same time everyone else has trouble pacing their diction and speaking normally, Betty Bronson sounds terrific. She has the best film presence of anyone in “The Locked Door”, she isn’t too theatrical and is just a joy to watch.

I don’t understand a lot of the reasoning behind pretty much everything that happens in this film. For example, the hotel proprietor (Keystone veteran Mack Swain) wants the cops to call the case a murder-suicide, because it’s more palatable than the idea of a man murdered by a woman he was trying to rape. That’s… odd. And Stanwyck trying to save Helen’s reputation is crazy, especially when you see Helen as the liberal flapper stereotype she was played as. Mordaunt Hall in The New York Times said, “It is true that the characters often behave as if they were under the spell of the director or the author, and therefore, apparently, they do not find it necessary to bother their brains about thinking, except so far as carrying out the action of the plot.”

Mordaunt is right. That doesn’t mean there aren’t a dozen good reasons to see this film. Check it out when you get a chance; it shows on TCM every so often.

FURTHER READING:

“The Locked Door” at Apocalypse Later

“The Locked Door” at Cinema OCD Media Room

SOURCES:

Film Daily, “The Locked Door” review dated 1/26/1930

Kenneth R. Porter of The Los Angeles Examiner, “The Locked Door” review dated 2/3/1930

Dick Hunt of The Los Angeles Evening Herald, “The Locked Door” review dated 2/3/1930

Louella Parsons in The Los Angeles Examiner, gossip article dated 3/27/1930

Mordant Hall in The New York Times, “The Locked Door” and “Two Women in Africa” review dated 1/20/1930

All sources except the Mordaunt Hall review are from G.D. Hamman’s Old Movie Section blog at this link and this one.

The door in Frank’s apartment is amazing.

Stacia, the review was nice and the picture were pretty. Now that you mention Rod LaRocque, have you seen his two films as The Shadow? The first one, The Shadow Strikes, is a straight but compromised attempt that fails pretty completely, but the second, International Crime, is a total send-up that might enrage pulp fans but was pretty good as a smart-alecky comedy, thanks largely to LaRocque.

You know, that chiaroscuro shot of a dishabille Stanwyck standing over La Rocque’s body with a revolver in her hand could represent the entire fim noir genre that was waiting just over the horizon.

A totally frenetic slap-dash of a film, tho, and early sound efforts were better handled by others. Mighty good lookin’, tho.

Flash forward about 40-odd years, and there’s Betty Bronson in “The Naked Kiss”, another mistaken murderer film with a vulnerable younger girl – one of her last roles, and she’s playing far from a wild thing there.

I agree David – I almost didn’t have room for that shot of William Stage Boyd next to the door, but I made room because you could see such detail. And the railing in Frank’s place is to die for.

I haven’t seen La Rocque in much of anything, I’m afraid. I’ll keep an eye out for “International Crime”.

Vanwall, I have to say that the biggest problem I had with the movie was the complete neglect of plot points and even characters. Dixon is a huge catalyst to the story and he shows up momentarily, then disappears for no reason.