Welcome to Day Eleven of the Camp & Cult Blogathon! Tomorrow is the last day, so if you have any submissions, make sure to get them in soon. I do accept late submissions, though not too late. Don’t show up in 2013 hoping to be added to the list, is all I’m saying. The master list of submissions is here, with new posts added every day.

***

Joanna is a film I first saw on Encore nearly twenty years ago, back when the channel was my go-to place for old films. Truly, while TCM has been my self-inflicted Master’s degree in filmology and filmonomy, Encore was my undergraduate degree, and of the amazing 1960s and 1970s films I saw, Joanna was probably the most influential. But it had been twenty years and I quite honestly didn’t realize how much of this film I carried with me, how many moments in this film informed my own viewing, completely unconsciously of course, never quite remembering when or how I first saw a certain tracking shot or specific editing technique.

The reason I didn’t know how influential Joanna had been for me was because it was so hard to find; I didn’t see it again until tonight, a full two decades after it last showed on Encore. Now, I watched it whenever it was on for those few months, as Encore had a habit of repeating shows several times. That explains why, to this day, the theme song from the finale of Joanna will get stuck in my head, often at random times but most especially if I hear the word “CinemaScope.”

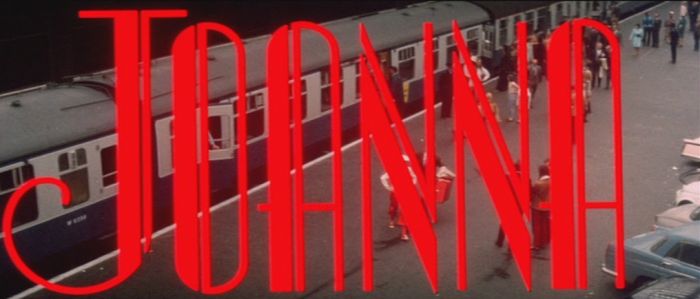

The opening of the film is black and white, turning to color when Joanna arrives on a train. The same technique would be used in Sarne’s Myra Breckinridge on the DVD restoration, which was discussed extensively by Marc at The Projector Has Been Drinking in a wonderful post for the Camp & Cult ‘Thon.

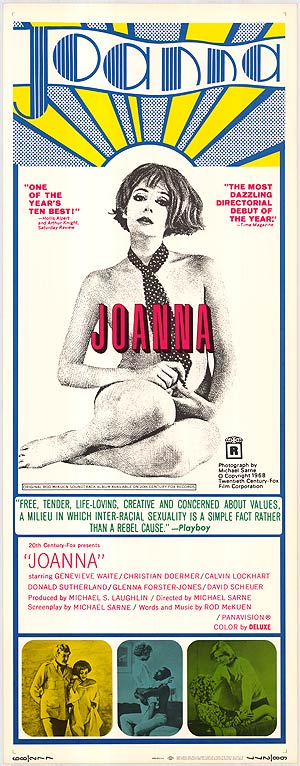

As you can see from the title screen, the aspect ratio is not quite accurate. Some of the left side is missing, which shows in the long-focus shots with action on the far left edge and in the credits. After years of not being able to find this anywhere, I got the recent “Flipside” version from the UK, which comes with both DVD and Blu-Ray. This article states it is the theatrical release aspect ratio, but I’m not convinced; it does accurately note the density fluctuation, which is prominent in many scenes. Areas that look like they were damaged during a pan-and-scan transfer still remain, too. This print, however, is the best you’re going to get, and it comes with two of Sarne’s early shorts, including Road to Saint-Tropez with Udo Keir. I mean, c’mon man. UDO. Also the extremely rare Death May Be Your Santa Claus. The full release is discussed here at BritMovie. Why don’t you own this already?

The IMDb — and lord knows where they got this, but it’s the plot most people are going to see when they look this film up — is “A provincial girl is entangled in the mod morality of London,” but that’s not really what it’s about. Joanna is about modern life in its way, of course, the modern life in the world of 1968, but Sarne has the wonderful ability to focus on the bits of life that transcend eras, that are common at any time in the history of humanity, and if you’re willing to look past the fashions and the makeup these themes become unmistakeable.

Joanna was quite influential in cinematic circles. In it you can see the seeds of Pennies From Heaven, both the original UK miniseries and the later Steve Martin version. My beloved Cleavon Little unquestionably channels Calvin Lockhart’s character Gordon for Sheriff Bart in Blazing Saddles, and the film anticipates by several years the trend toward 1920s and 1930s nostalgia that hit its peak in the 1970s. Michael Sarne’s direct referencing of classic Hollywood film stars mirrors the homage and imitation from La Nouvelle Vague, but with a more vicious edge, basically praising the image of old Hollywood by deconstructing it to the point of destruction and re-forming it into a 1968 context. It rids these images of much of their sentimentality, and truly, I don’t think one could ethically indulge in a sentimentality of 1930s Hollywood while also exploring the issue of race in 1968 Western culture; at the very least, waxing nostalgic over unmodified 1930s films and all that they represent — including base, undiluted racism — would undermine the relationship between Joanna and Gordon in this film.

Both Fellini and the New Wave were obviously influential on Sarne, especially in his dedication to a non-linear narrative. The conceit of showing a flashback to something a few moments before, sometimes maybe only 15 seconds prior, is interesting and it grounds Joanna’s intent, but by explaining Joanna’s thoughts so literally there is a loss of ambiguity. That narrows the perspective of the film and cuts off viewer interpretation in a way that I’m not entirely sold on, however.

Michael Sarne is clearly quite knowledgeable about cinema, and he also just loves movies, which isn’t always true of those who know a lot about film. His love of films is also a love of filmmaking, which is quite evident throughout. There is a terrific sequence early on where Joanna is seen in a dark sage green jacket and white jumpsuit, walking away from her art class and telling her friend she doesn’t know where she’s going.

As she skips off, her clothes begin to match her surroundings completely, the green of the plants the same green as her jacket, the white of the walls the white of her shorts. She wanders into a friend’s studio, with the railings the same green and the walls the same white. Joanna meets new people, all having details of their wardrobes in the very same shade of green. It’s absolutely delightful, drawing all characters together while visually acknowledging the shallow, surface relationships these people are forming during these scenes.

One can’t discount that the color coordination of outfits truly is a sly metaphor for the color-coded society Sarne explores in Joanna. The title character (played by Geneviève Waïte) is an 18-year-old in London to attend art school. She’s not particularly appealing, being selfish and rude and naive and greedy, but she gets away with it like pretty much every ultra mod beauty in the Swinging Sixties did — by being adorable and willing to hop into bed with anyone.

The fourth wall is broken frequently, and the iconic images of classic Hollywood films are literally papered over much of the background.

The fourth wall is broken frequently, and the iconic images of classic Hollywood films are literally papered over much of the background.

Joanna meets up with Beryl (Glenna Forster Jones) and her brother Gordon (uber-dreamy Calvin Lockhart), who both know Lord Peter Sanderson (an amazing Donald Sutherland). Sanderson takes his girlfriend Beryl, Joanna and her boyfriend Dom on a trip to the tropics, spending his copious funds to treat others to a fun time and have as much fun as he can before his unspecified illness eventually kills him.

Throughout the film, Joanna finds herself in a series of inappropriate relationships, being hit and insulted and destroying marriages almost daily. She finally finds her true love in Gordon, and after a series of events straight out of a gangster-themed pre-code, she loses Gordon and is forced to grow up. There are larger themes of social hypocrisy, as well as exploration of Joanna’s deep neuroses.

What I’ve noticed in a lot of reviews is that her dream/daydream sequences are taken as literal, or as just random shots inserted by a confused Sarne, though they are obviously comedically Freudian dreams and I fail to see how that isn’t easily recognizable. When she’s threatened by Beryl she daydreams about having the black woman as her servant; when she’s rebelling against Daddy she dreams of finding him mostly dead but still with enough strength to beat her. When real life with Gordon starts to mirror her fantasy daydreams of a better, more glamorous past, she finally finds the world she wants to live in.

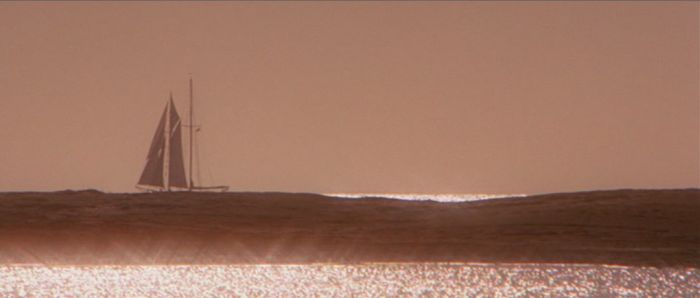

That’s not to say there are no faults to this film, because there are — a lack of focus and a desire to be as candy-coated and ultra mod as possible being the primary problems with the film. Take this series of shots, beginning with Sanderson, Beryl, Joanna and Dom having lunch, then a transition shot of the nearby sea, then the three friends later that day discussing whether Sanderson is ill or not:

Beautiful, saturated colors, lovely composition, probably some of the nicest cinematic shots of a glistening sea I’ve ever seen. Yet the acting in these scenes in some of the weakest in the film, almost as though a script malfunction required an impromptu ad lib from actors completely unable to meet the challenge.

Even the most ardent Michael Sarne fan — and I include myself, given my undying love for Myra Breckinridge — must admit that there is precious little context for the social commentary he strives for, and that the story of a flighty art student’s sexual escapades needs more than earnestness to become a full-fledged film. Still, for anyone who can get past Joanna‘s questionable reputation and not be distracted by Waite’s generous selection of wiglets, it’s more than worthwhile.