Dick Clark was especially cranky that August afternoon in 1966. For a decade he had been asking harmless questions of both guests and giggly teens on “American Bandstand,” but today’s silly subject irritated him, made him self conscious. A professional study had recently claimed most men within a few years would be wearing long hair. Sensing perhaps that his own mathematically correct hair was no longer hip, he must have felt this new singer, a young man stalwartly holding on to a magnificent late-era rockabilly pompadour in the age of shaggy hair, was a kindred spirit. After the rocker threw a sexy hey-baby head swagger at the girls, Clark asked him his thoughts on long hair. The kid managed an answer of a sort, too nervous to make much sense but also entirely uninterested in the subject. Frustrated, Clark bared his sharp teeth in an attempted smile, then asked the singer the title of his new album. More nervous than you’d expect a tall, rebellious kid clad in deliberate brooding black to be, he stammered out: “The album is called ‘The Neil of…’ uh, ‘The Neil of…,’ no, it’s called ‘The Feel of Neil Diamond.'”

For decades, Diamond has spun the romantic tale of that all-black wardrobe of his early days as a manifestation of his intense performance insecurity. But amidst a culture that dictated bright clothing, his dark monochrome look was bound to generate attention. When he played the Hollywood Bowl in 1966 he strode on stage in black from head to toe — including a jet black guitar slung over his back — and made a scene. “I didn’t know what the fuck to do, so I wore a big cowboy hat and came on very cocky,” he said. “The whole audience just went ‘Whooaa!’ And it blew my mind. I couldn’t follow it because I didn’t know how to sing or anything, but it was fantastic!”

For decades, Diamond has spun the romantic tale of that all-black wardrobe of his early days as a manifestation of his intense performance insecurity. But amidst a culture that dictated bright clothing, his dark monochrome look was bound to generate attention. When he played the Hollywood Bowl in 1966 he strode on stage in black from head to toe — including a jet black guitar slung over his back — and made a scene. “I didn’t know what the fuck to do, so I wore a big cowboy hat and came on very cocky,” he said. “The whole audience just went ‘Whooaa!’ And it blew my mind. I couldn’t follow it because I didn’t know how to sing or anything, but it was fantastic!”

Neil is being disingenuous when he says he couldn’t sing, but the “or anything” is absolutely true. Aware that he was not performing on a professional level, he took acting lessons with Harry Mastrogeorge, which even resulted in a little acting work. Further, Diamond’s manager Fred Weintraub allowed him to appear as a fill-in act at The Bitter End for the much-needed practice. Weintraub knew there was anger over Neil’s presence; patrons and other performers expected hipper folk acts rather than the disaffected semi-country stylings of Neil Diamond. “He was a fish out of water,” said Weintraub, as the crossed arms and tilted heads of the ultra-hip audience attest. Neil was initially encouraged to connect with the audience with banter between songs, but the result was so resoundingly awful that Weintraub gave Neil a new rule: “Stop talking between numbers.”

The reason Weintraub was willing to irritate his own customers was because Neil had a presence that transcended his uneasiness:

Neil’s voice is charming and compelling, even when it cracks and wavers from stage fright. He’s awkward, protectively drawing in his shoulders, and he must have made everyone watching uncomfortable. But there is an intensity there that goes beyond the brooding exterior, and the most fascinating thing happens just after the one minute mark: When he sings “I’ve been misunderstood for all of my life,” you believe it. Then he looks right at you through that camera and repeats what they say — “The boy’s no good” — and you know he’s been on the sharp end of those exact words, probably even believes them. “Girl” is on the surface a typical poor-boy lament coupled with the celebration of a good old-fashioned deflowering, but it’s also very much about a young man navigating through a society that offers him little more than humiliation and rejection.

Still, it’s a strangely amateurish performance for someone who that same year was named “Most Promising Male Vocalist” by Record World and “Top Male Vocalist” by Cashbox, tying with Frank Fucking Sinatra. Despite Neil’s obvious performance issues, by the end of 1967 he was embarking on a calculated move to become a bigger star. “I can’t settle for easy lyrics anymore,” he told Newsweek in early 1968. “My goals have changed. I don’t just want hits, I want to write important songs.”

Writing these important songs meant, apparently, blowing the hell out of every bridge he had ever stepped foot on. He acrimoniously left his recording company Bang Records in a situation that became ugly in a carrying-a-gun-for-protection kind of way. Leaving Bang also meant leaving colleagues Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry, the people most responsible for making him a star. But Neil didn’t want regular, unadorned stardom, he wanted super stardom. To that end he soon left New York, his manager Fred Weintraub, and his pregnant wife, moving to L.A. with the girlfriend he met when on “Clay Cole’s Diskotek.” In the market for a new record company and probably with hopes of some acting gigs, Neil signed with UNI, owned by MCA/Universal Pictures. They sent him to more acting lessons, a few screen tests, and his new management scheduled him on the biggest national variety shows. To go with this new life was a new image, the pompadour and black leather replaced with long hair, flower power shirts and, briefly, a beard.

When asked in 1976 if the beard was a momentary attempt at hipness, he claimed it was actually to avoid the private investigators his first wife had hired to find him after he ran off to L.A.

The official story of Neil’s career, or at least as official as things ever get, follows a standard linear trajectory: Diamond began as a scared kid and, through hard work and determination, developed into a professional entertainment machine. “He went from nervous, uncertain novice to the exacting, self-disciplined performer you see today,” said producer Tom Catalano in 1982. And this is true to an extent, but in one of the many contradictions that defines Neil’s artistic existence, he never completely overcame the nervousness that plagued him early on.

In 1969, he appeared on “The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour” while uncomfortably nervous, blinking after catching sight of the camera, so flustered he had to shake his head to snap out of it. Less than two weeks later on Ed Sullivan, he did it again. Many years later in 1983 he appeared on “Live… And In Person” to perform “Heartlight.” He is indescribably beautiful, the audience is responsive, and the ladies are so excited they’re probably building makeshift trebuchets out of theater seats in order to fling themselves on stage, yet Neil is uneasy — the shifty eyes and plastered-on smile give him away. More recently in 2006, Neil powered through a short live set on QVC where even the unconditional love of about 200 blissed-out fans could not reassure him.

Diamond is well known for his emotional stage presence and autobiographical songs which, in yet another essential contradiction, is very odd for someone who is so famously reticent to reveal anything about himself. So reticent, in fact, that you can grab any random batch of interviews or articles and unearth immediate contradictions, lies, specious stories, and fudged dates to cover past indiscretions.

That Neil Diamond lies is not surprising. Sun Tzu said a general must utilize false reports and appearances to maintain order, after all, and what is the world of celebrity if not a constant war against irrelevance? The problem, though, is that Neil is just so damn bad at lying. He has explicity stated many times that he was “lonely” and “solitary” as a child (People Magazine 1982, Rolling Stone 1976, respectively). Yet in 1989 he told host Terry Wogan that he didn’t “remember being particularly lonely” as a child. He continued on, gradually admitting that being solitary was “only a small part of me,” and was so unconvincing he promptly got himself booed by the audience. Clearly, for a singer who relies on emotional revelations in purportedly autobiographical songs, these inconsistent stories and the usual celebrity PR bullshit risks undermining his art. But to ask a question critics better than I have asked for longer than I have been alive: Does Neil Diamond actually achieve art? Perhaps it’s only pop music product, the sentiments of his songs merely carefully-crafted gimmickry. Maybe it is all an act, the almost-tears, the insecurity, even the nervousness.

Except. Except. Those appearances where he is clearly nervous are reason to think that Neil Diamond is not all celebrity product. Being palpably anxious on “Live…And In Person” in 1983 could never have resulted in anything positive for him at that point in his career. And let’s be honest, you have to be Liza “Hi Georgia!” Minelli to make the news after an odd QVC appearance, so pretending to be afflicted with stage fright would be pointless. He continues to tell differing stories to this day despite many people pointing to the contradictions for decades as proof of his insincerity; if he’s lying for PR, he’s doing a rotten job of it. There is no way to explain Neil Diamond satisfactorily except to take him as genuine while accepting that his career is a combination of talent, inexplicable luck and frustrating contradictions. That is why it is completely consistent to state that Neil Diamond offers up his soul to an audience while simultaneously hiding in all black or behind hundreds of shiny, attention-deflecting beads. It is also completely consistent that Neil Diamond is both occasionally scared to distraction and enormously confident on stage.

Much of that confidence comes from the creation of a killer rock hook in the form of Brother Love. The good Brother is a revivalist, the star of Neil’s 1969 single “Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show,” a song with the unique twist of having the singer essentially play three characters: Narrator, opening act working the crowd, and finally Brother Love himself. When Diamond embarked on that power move in late 1967, he went nearly two years without a Top 40 hit. “BLTSS” broke that streak, resurrecting his stalled career.

If you are not familiar with “Brother Love,” you absolutely must read The Minister’s essential post at The Ministry of Truth. When you reach The Minister’s annotated lyrics, listen to the song while reading along — and you want to listen to this specific 45 RPM single version, crackles and all.

“Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show” is undeniably cinematic. The lyrics tangle into the music so deeply they cannot be extricated; without one, the other ceases to exist. As the song unwinds you can feel that summer night air lazily wrapping around you, you can taste the salty sweat running down your face across your lips, making you impatient for the preacherman’s arrival. The insistent beat of the music makes it worse, you think, or maybe it’s better to try to dance it out, you’re not sure anymore. And when he arrives, his sultry words offer less comfort than the cracking voice with which he delivers them. The girls in the choir dutifully join in with their Halle hallelujahs! but soon start singing their own path to salvation as Brother Love shrieks his message of love and devotion into the crowd. But then it fades too quickly, as light absorbed into black, over before it could linger like you wanted it to, like you needed it to.

In his post, The Minister rightly points out that Neil is just beginning to let go by the final run-through of the chorus, bemoaning the lack of a “full-blown vocal wigout.” What The Minister of Truth wishes for, time delivers: A mere six months later, Diamond was unleashing the persuasive screams of Brother Love, which you can hear in this almost fearless live version on Gold: Recorded Live at The Troubadour. Though Neil still had insecurities at The Troub, he played them as joking banter, having learned how to turn those insecurities into assets. And he had also learned Brother Love was a surprisingly captivating figure.

Captivating an audience was not new territory for Diamond. In 1967, still be-pompadoured and rebellious — and wearing white despite telling Ben Fong-Torres that he wasn’t confident enough to wear white on stage until 1970 — Neil worked the excitable girls in his audiences with “Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon.”

Neil Diamond: “At that time I was doing rock and roll shows in 1966 and ’67, and most of the audience were teenaged girls 14 and 15 and 16, and so that was basically what my audience was, teenaged girls. So I guess I wrote a few of those early songs for them, you know. I think probably “Girl, You’ll Be A Woman Soon” was written to be performed in front of an audience of girls, which is the best audience in the world ’cause they go crazy. They go nuts, and it’s fun for a guy to be able to do that.”

Neil Diamond: “At that time I was doing rock and roll shows in 1966 and ’67, and most of the audience were teenaged girls 14 and 15 and 16, and so that was basically what my audience was, teenaged girls. So I guess I wrote a few of those early songs for them, you know. I think probably “Girl, You’ll Be A Woman Soon” was written to be performed in front of an audience of girls, which is the best audience in the world ’cause they go crazy. They go nuts, and it’s fun for a guy to be able to do that.”

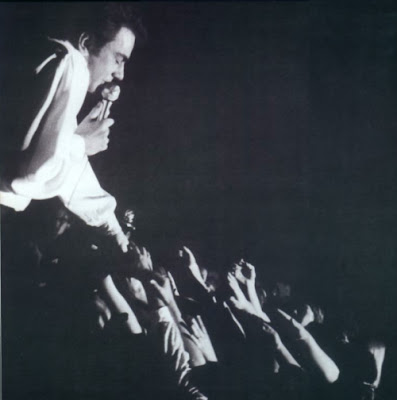

Jack Spector: “He’d go down on his knees and work the girls at the edge of the stage… and touch hands, fingers. And he’d single one girl out, and maybe he would help lift her to the edge of the stage, and he’d work to her. He’d sing the entire song to that one girl, who at first would be giggly and nervous, but after a while would be looking at him in rapt attention.”

It is worth noting that Neil said in 2011 that he “should have realized the potential power of songs and been a little more wary.” It’s infuriating, because clearly he did realize the power of his songs and used it for evil. Sexy, underaged evil. When he contradicts himself you can’t know if he’s being disingenuous, a raconteur, in denial, or just fucking with our heads. And as someone who doesn’t believe his “Longfellow Serenade” story for one moment and who has profound, deep, intellectual questions about the “Eice Charry” story as well, trust me when I tell you I think he fucks with our heads. A lot. And then chuckles about it while shuffling around his house in comfy slippers and watching old “Ryan’s Hope” episodes he recorded on Beta back in the day.

The creation of Brother Love had its own stories, often varied. In 1970 on “The Johnny Cash Show,” Neil told a new version of the song’s genesis via a hilariously unconvincing spoken word bridge:

On Cash’s show when Neil transforms into Brother Love, Diamond starts moving in a way that gives this Southern Missouri girl born and raised a little chill, because those hunched shoulders and bopping heels are pure 1970s televangelist, seen every Sunday morning on Springfield television when I was growing up — always with a superimposed mailing address to send your checks to, mind. Someone taught this nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn to move like that, you know. They should probably be ashamed of themselves. At least a little.

Less than a year after the Johnny Cash Show, Diamond appeared on the BBC institution Top of the Pops in a remarkable performance, 38 minutes of God-given proof that Neil Diamond, while having had an exceptional career, once held the promise of a sublime career but the years did not fulfill that promise. Gone is the overt nervousness, yet one senses that Neil would still like nothing more than to hide behind something, probably his guitar if it were only large enough. The cinematographer gets us in so close we’re intruding on Neil’s life, really, consuming his every reaction, twinge, those long eyelashes, the pained scowls and barely-audible hums and whispers at the end of “I Am…I Said.”

All the proof you need that “IAIS” was too much for him is contained in the performance of “Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show” immediately after. Though Neil wriggles his little torso and screams with delightfully fetching repression, he never abandons himself enough to reach the fever pitch of those Sunday morning television preachers. He spends a majority of “Brother Love” with his eyes closed even after he becomes the preacher, so much so that our besotted BBC cinematographer backs away from those magical close-ups, wisely realizing that actual physical space is less distancing than a close shot of eyes clamped defensively shut.

At first blush, the entire 1971 BBC show seems to reveal a Neil Diamond that no longer exists. But amidst the wriggling sermon of Brother Love one can hear the vocal tricks Diamond would overuse in later years, the growling and eee’s and the hissing. That sensitive, sleepy-eyed poet on the BBC was already slipping into history, soon to be eclipsed by a desirous preacher howling his lust to his devout followers. By the “Soolaimon”/”Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show” mash-up during the 1972 Greek Theater series, the good brother’s soul-swelling screams were well known, even expected. Two months later he appeared in a 20-show Broadway engagement at the Winter Garden Theater. His friend and assistant Totty Ames said of these performances that “he started off at a high-fevered pitch, and every performance was that way.” “BLTSS” no longer mirrored the lyrics about a sermon starting soft and slow, but rather opened with screaming and closed with louder screaming.

The improvement in Diamond’s stagecraft during these years cannot be overstated. By Hot August Night he was entirely in control, equal parts ego and talent like any good rock star, and utilizing both his strengths and weaknesses like an experienced general. Hot August Night and those Broadway shows cemented his superstar status, at which time he did the unfathomable: He quit. It was not a complete resignation but a sabbatical, an indefinite pause largely spent in psychotherapy “three, four, maybe five times a week.” He stared a hole in the therapist’s wall every session for a year before uttering a single word.

Neil went back to touring in 1976, hitting Australia after a few warm-up gigs in the U.S. During the Australia tour, Diamond appeared on his first major television interview. Neil is defensive and articulate, alternating between honesty and blatant untruths, wearing eccentric Italian sunglasses as a talisman to ward off desirous cinematographers who dabble in the black art of closeups. Michael Schildberger is a phenomenal interviewer, but even his gentle approach results in one unmistakeable flash of anger that those glasses cannot hide: Neil did not like it when Schildberger suggested his lyrics were occasionally “unusual.”

Neil is brave, by the way. I know it’s hard to tell when he’s hiding behind expensive shades and a purposely flattened affect, but he is. Look, I will never understand him. He’s a frustrating amalgam of honest emotion and talent plus cold, humorless commercialism. In the wake of that 1971 BBC performance it’s difficult for me to accept much of his later artistic output. But despite not understanding a damn thing about the man, the one thing that I will never back down on is my genuine belief that Neil Diamond has balls of fucking steel. And I believe this precisely because of those “unusual” lyrics, those flea wings and chairs and brangs that weren’t merely unique personal expressions but sheer fearlessness. He must have known some jerk (or critic, and since we critics are jerks, it all evens out in the end) would think he was simply too dim to conjugate a verb, yet he did it anyway. The man never apologizes for his existence. For 45 years he has continued to create and connect and perform despite critical comments that would destroy others, all the while being so scared you could see it in his eyes. It’s artistic bravery in the face of decades of cultural hostility, and for that Neil has earned my undying admiration.

Neil is best when he’s performing songs written about himself for himself, which some critics dismiss as misguided self-flagellation, but the fact that so many others relate to what Neil writes proves that his art is, on some level, universal. For example, “I Am…I Said” is about his own unquestionably singular situation. It was written soon after Diamond left behind his entire world on the East Coast. He was on the verge of becoming legendary in 1971, but in terms of acting, he was an amateur when given the chance to test for the complicated role of Lenny Bruce in an upcoming biopic. Frustrated with his performance, alone, and certain he had failed, he began to write “I Am…I Said” during a break between scenes. Almost no one else in the world could possibly relate to where Neil was at that moment, yet when we hear “IAIS,” we do. Even those who squint and scratch their head over that chair lyric know deep down what it’s like to be so desperate for human interaction that you talk to an empty chair… so desperate for human interaction that you distill down an impossibly unique personal experience into universally-recognized emotion, then force yourself to perform it publicly, even if you have to do it while closing your eyes and pretending no one else is in the room.

When Neil is on stage, every emotion comes with his implicit desire to connect with someone, even if said someone is an anonymous sea of thousands of faceless people in the dark. During the ’76 Australia tour Neil seemed, at least for the moment, that he had hardly been away from the stage at all, let alone for nearly four years, although there was an unmistakable change in how he attempted to connect with the audience.

Sydney, Australia, 1976

This song lasted 4 minutes and 42 seconds. At 4 minutes and 43 seconds, 38,000 people in the audience turned to each other and asked, “Uhm, so… did we just have sex with Neil Diamond?” It’s refreshing to hear a song that so fully acknowledges the futility of caring about lofty subjects like the impermanence of art when one is super damn horny. What makes this particular performance so compelling (beyond the ultra tight leather pants) is that he is not faking anything, his relationship with the audience and the song is real. That is genuine Grade A 100% Neil Diamond sexuality right there, folks, and we’re all metaphorically invited to jump right in, the water’s fine.

Three months after the Australia tour, Neil performed seven shows in Las Vegas at the newly-opened Aladdin hotel. When Ben Fong-Torres interviewed Neil earlier that year, he sat in on the fitting for Neil’s Vegas outfits designed by Bill Whitten, the man responsible for all of Neil’s glass-beaded expressions of self doubt. I don’t know if Neil ever realized that it was futile to try to hide his soul behind interesting wardrobe choices. He hadn’t discovered it by 1976, that’s certain. For the Vegas show he was mimicking Elvis directly, instructing Whitten’s studio to create three high-collared, bellbottomed outfits for multiple costume changes: Yellow for most of the concert, white for the “Jonathan Livingston Seagull” suite, and for Brother Love, hiding again in all black.

Neil had been in excellent form in Australia, maybe a little tired of his older songs — he had made changes to several, most notably by no longer singing the opening chorus of Brother Love’s Travelling Salvation Show but performing it as spoken word — but something happened in the four months between Australia and Las Vegas. This change is obvious enough that several articles and books have mentioned it, many blaming an overzealous drug bust lead by an LAPD officer known affectionately as “Psycho.” This raid the night before the Vegas gig purportedly left Diamond so paranoid that he holed up in his Aladdin hotel suite and rarely ventured out except when on stage.

At the July 4th performance, Neil seemed outwardly relaxed and the audience was in good spirits. What they didn’t see, though, was his obvious detachment. He was distant, likely exhausted, wringing his hands and fiddling with his guitar pick like he was trying to break it. His demeanor was full of swagger and overwrought enunciation, what Robert Christgau once called “the high-tone ridiculous” and, despite Ben Fong-Torres’ claim otherwise, early in the set Neil threw in a few Elvis-esque martial arts moves to go with those outfits.

Very little Neil said or sang that night seemed authentic. Watching the ’76 Vegas performance is like watching the wave of Neil’s superstardom — and possibly sanity — break and retreat, Hunter Thompson-style, leaving behind a high water mark and a few intangible memories of what once was. He had such an emotional distance from his own songs that he inserted blatant sexual innuendo into “Shilo,” presenting his ass to a front-row patron and turning a song about a lonely young boy’s imaginary friend into an episode of “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom” with guest host Sigmund Freud.

There was one genuinely emotional performance that night: “If You Know What I Mean.” It’s an autobiographical tale of a couple who recall life before they “gave it away for the sake of a dream,” a song penned when Neil was only 34 years old, already longing for a lost life full of unspecified things given away. One can hear too, I think, regret for the things he had gained with superstardom, things that were maybe not so easy to resist. It’s been 36 years since he wrote that song, yet I want to ask Neil what he gave away, because I think if there is a Rosebud moment in that man’s life it would be in his specific answer to that vague song lyric. But Neil Diamond would never answer that question and, when I’m being truly honest with myself, I know I would never ask it. I like to think I have finally learned that asking scary questions inevitably leads to scary answers.

As that July 4th set in Vegas continued, everyone on stage gradually showed signs of something being very wrong. Exhaustion perhaps, or a bad sound system or paranoia thanks to “Psycho” of the LAPD, too much downtime in Vegas or maybe not enough, who knows. Whatever the reason, the band started to fall apart by the time they reached “Holly Holy.” Guitars were out of tune, everyone made obvious errors, the drummer loudly and inexplicably clapped his hands directly behind Neil as he sang a soft ballad, and musicians slammed home each individual note like an overzealous high school pep band.

Neil, too, was completely off the rails. That night, the intensely personal “I Am…I Said” meant nothing anymore. Where emotion should have been, a dead, blank void existed instead. As he sang, Neil indulged the egotistical side of his insecurity, severely overemphasizing the lyric “when you talk about me” to make sure everyone did indeed know that it was all about him. He drew out the “me” for several beats and even pointed his thumbs back at himself like he was the motherfucking Fonz. He was obscenely detached, engaging in a destructive self-loathing never meant to be shared with others, yet there it was, not only performed live in front of thousands but filmed for posterity.

Neil leaves the stage for a few moments for a costume change, returning in a blinding white Jesus-Elvis outfit for the “Jonathan Livingston Seagull” suite, the perfect look to accompany the pseudo-Christian imagery scattered throughout. His last wardrobe change is into all black for the planned encore. In a particularly cheeky move, Neil immediately followed the deliberate invocation of one or more heavenly deities in the “Seagull” suite with the dark menace of Brother Love.

A moment into the performance we get a blessedly brief look at Neil’s face. He’s predatory, all dangerous, vacant eyes and slow, lingering growls. Make no mistake, he is not growling the lyrics because of his smoking habit or laziness or any of the other speculative reasons fans have given over the decades. He is growling at that moment because that is all he can do, brothers. He is a tired man who ain’t got where to sleep, a hungry man who ain’t got what to eat. His devout assembled came for salvation but found the good brother in need of his own.

As the sisters on the stage sing their Halle hallelujahs! behind him, a few of the congregation this night reach out in hope of the preacherman’s healing touch. Not quite two minutes into the performance, Neil does a subtle double take at one girl’s outstretched hand, the same blonde teen who delivered unto him a flower as he sang about giving it away for the sake of a dream. As Neil begins to sermonize to the many thousands assembled, he steps back from the girl into the deep red glow of the stage, head turned, asking not to be tempted. Halle hallelujah! But the Lord gave us two good hands, brothers and sisters, one for the givin’ and one for the takin’. Eyes closed, facing away, Brother Love’s arm stretches back to meet hers. The unmistakable glint of a key is seen in the girl’s thin fingers. Gently placed in his open hand, her key disappears as he relishes the acquisition one finger at a time. Halle hallelujah! He preaches to others but he doesn’t stay with them long, brothers, he has to return to that poor lost lamb. Shrieking now, no longer words but desperate guttural pleas for salvation, our most holy brother is back at the girl with a final, glorious amen as the lights go down. The lights snap back on immediately, revealing Brother Love nearly crushing this girl’s hand as he stands slightly hunched, tensing, tensing, giving way to spasm, snapping upright in release. Halle hallelujah!

Released but most certainly not saved, Neil Diamond circled the stage before disappearing behind the lights, triumphant in knowing he need not reveal his soul when outsized sexual desire would do, blessed with finally having found something large enough for him to hide behind: Brother Love.

This is part one of a planned three parts, but I don't yet know when the next two parts will drop.I'll be posting all my sources later on, but in the meantime, just leave a comment if you want to know a particular source now. Note that I won't be around today (Monday) until the evening.

I'm totally overwhelmed by your blog post. Can't wait for the other parts! Lovely work!

This is unbelievably good. Most bloggers have a passion (obviously) for the subjects they write about, but that passion isn't usually combined with such an articulate, entertaining voice.To be honest, I never even cared about Neil Diamond until I read this. I stumbled on this blog via Twitter and was immediately engrossed by your writing. You made me care about a subject that I had no interest in. Very nice work. Can't wait to read more.

Wow. Wow. Wow. Amazingly well-written piece. I've been a casual Neil Diamond fan for years, but I never knew much about him nor had I seen clips of him performing. It's amazing that someone with such obvious stage fright could become such a mega star.

RFP: Much like Dave E. I had also been just a casual fan (actually, more like a Hot August Night snob) and had never known too much about Neil beyond his music.However, through Stacia's passion for the subject matter and full dedication to researching his career I found out I was astoundingly ignorant of Neil's history and origins. Now, the name Neil Diamond doesn't just conjure up memories of a great double live album I grew up listening to but of a complicated, amazing, infuriating and often very lucky man, who's career makes me laugh, cry and otherwise sends me into a complete head spin.In short, thank you Stacia. It's been an amazing journey of discovery : )

Thank you Mariam and Dave! You as well, RFP, that is extremely kind of you to say.Dave, I agree that it's unbelievable to see someone so nervous so many years after they had already become a huge international star. Vincent, I most certainly owe you apologies for all this. It hasn't been boring, but there's only so much entertainment value to be had in a chick goin' crazy.Also, I forgot to mention that I have a TON of people and websites to thank for their help, and have a post in the works about that — if anyone reading this is thinking "Hey, she should thank me" then you're probably right!

I read your post yesterday and have returned to applaud.

Thanks, MJ, I appreciate it.

That's what I'm talking about, baby! Skip the picture posts and space fillers. Give me this every time! I don't mind long lapses between posts as long as this sort of thing waits for me on the other side! Can I get an amen, brothers and sisters! Speaking of Brother Love's Traveling Salvation Show, I loved this well written (let me repeat that: well written) analysis of how Diamond has handled and evolved through this song. I never understood the religious faction's opposition to this song. I remember a recess when I was in the 6th grade – Eric Baddie had a transistor radio and Brother Love came on. He cranked it for all the tiny speaker would take, till the song was barely more than a loud crackle. I remember three girls screaming the chorus at the top of their lungs, shimmying around. In other words, I always felt the song was a complete homage to the supreme power of spiritual awakening. Oh, and I love the moment when Diamond (Brother Love) receives the healing touch of the key from the long, female arm with the graceful hand. I also loved the way the fan let her finger glide over Brother Love's palm as their hands parted. Smooth, Neil. Smooth as can be.

Mykal, you always know the exact right thing to say, thank you so much.I love your recollection of hearing the song on the radio! I wasn't born when the single dropped, but I doubt it got a lot of airplay in Southern Missouri. Our local AM station KJEL didn't play "Soolaimon" until the late 1970s.Isn't the key amazing? It's beautiful, the way the light hits that key, and how that stage right camera caught it so explicitly.Honestly, I am probably going to keep up with the picture posts and shorter things for at least a while. I've carved out a chunk of time every day for writing, and I gotta make sure I've gotten my proverbial million words out of the way.

Stacia: OK. I'll live (grudgingly) with the shorter posts for these sweet entries. Again – great job.

You're very tolerant of me, Mykal.

Well, this was definitely worth waiting for, and I say that as someone who couldn't care less about Neil Diamond. Not a hater, I just always thought of him as a campy figure, a kind of less aggressive Tom Jones, probably because my mother liked him (the only "rock" albums my parents owned were a couple by Neil, one by the Beatles, and the rest of their collection consisted of Kingston Trio-style folk revival and Dixieland Jazz of the sort one encountered at Disneyland's Carnation Plaza). In my defense, I'd never actually heard Brother Love before now, and that was kind of eye-opening.But the mark of a gifted critic is to make her subject interesting to even an indifferent observer, and I was fascinated from the opening paragraph to the beautifully wrought ending. How you managed to make Neil Diamond (who I have studiously ignored since 1982 — having decided that Heartlight would end its days as the jingle for a brand of electronic medical alert bracelets) into a larger than life, even tragic figure, is a pretty neat trick, and I haven't a clue how you managed it.

Sun Tzu said a general must utilize false reports and appearances to maintain order, after all, and what is the world of celebrity if not a constant war against irrelevance?

This is probably the pithiest summation of modern American culture I've ever read.

He had such an emotional distance from his own songs that he inserted blatant sexual innuendo into "Shilo," presenting his ass to a front-row patron and turning a song about a lonely young boy's imaginary friend into an episode of "Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom" with guest host Sigmund Freud.

Thoughtful, perceptive, informative, and yet with that trademarked Stacia snark. Can't wait for the next installment (not to say I would object to another chapter of Phantom Creeps in the meantime, but I realize you can't produce this caliber of work without budgeting your time).

Scott, you are far too kind. Thank you for your comments, I can't tell you how much I appreciate what you said.I'm seriously considering doing a Phantom Creeps post just to get my mind reset. Oh, and anyone who is rethinking their opinions on Neil Diamond, take it from me, you don't want to get too deep in this. Your life will turn into a psychological thriller if you're not careful. You'll be watching Possession and think, "Yeah, that's kind of how I acted when I first heard 'Lordy'…"http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZhDpf92ff50(P.S. When I was looking this up on YT, I discovered there is a tribute band called Nine Inch Neils. I am horrified and delighted at the same time.)

Some Neil on 'Mannix' : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZyRXFd1Hv2oAs an old Neil fan, I'm blown away by what I learned from this post. Thx!

Thanks Clarence!I like Neil on "Mannix." Well, I just plain like "Mannix" first of all, and I also like Neil's hipster basement musician character. It's so strange to our 2012 eyes to realize that at one point, Neil Diamond was not only hip but considered underground, at least for the "Mannix" intended audience.

10/11/2012: This post and comments have been imported over from the old SBBN blog. Sorry about the formatting on the comments that were imported, they look like gibberish. Thank WordPress for that.

A few edits were made: I added a link to the Las Vegas 1976 Shilo performance, which is now on YouTube, and corrected the date of the QVC performance from 2008 to 2006. Also note that the 45 RPM version of Brother Love is no longer on YouTube, and I’ll try to get a replacement link up as soon as possible.

This blog post is brilliant! You have rare insight indeed…well done!

Thanks Jeannine, I appreciate it!