This is the SBBN entry for the 4th annual Italian Horror Blogathon hosted by our good friend Kevin at Hugo Stiglitz Makes Movies. The ‘thon runs for a week, so keep checking in!

This is the SBBN entry for the 4th annual Italian Horror Blogathon hosted by our good friend Kevin at Hugo Stiglitz Makes Movies. The ‘thon runs for a week, so keep checking in!

***

Actress Carroll Baker spent 1967 reeling from a series of Hollywood setbacks, all of which began, somewhat ironically, after she achieved the biggest commercial success of her career. Having had a solid film and stage career for nearly a decade, Baker accepted the role of a Jean Harlow-esque blonde bombshell in The Carpetbaggers (1964). As she later said, she took the role because it was far removed from her iconic appearance as Baby Doll a decade earlier in the infamous film of the same name, and because she had thought the book was “great fun.” The soapy, scandalous Carpetbaggers went on to become a massive success, earning over $28 million, the fourth highest-grossing film of the year. It resurrected the careers of a few aging Hollywood actors, and briefly shot Baker and her leading man George Peppard into stardom.

Thinking Baker was on the cusp of international fame, Carpetbaggers producer Joe Levine signed Baker to a multi-million dollar contract, then immediately screwed her over. Levine was a bully and a hack, one of those long-time Hollywood producers who managed, simply by being around for decades, to produce a few classic films, but mostly spent his time on films like Santa Claus Vs. the Martians (1964) and The Oscar (1965). Thanks to this utter lack of ability and taste, Levine got the brilliant idea of casting Baker as Jean Harlow yet again, and contractually forced her into Harlow (1965). Baker had been trying to resist sex symbol roles to avoid typecasting, but Levine and her own husband Jack Garfein pressured her:

“…my husband thought it was all terrific as long as I kept bringing in the money. I started objecting to everything, but it was too late. The sex-symbol image had already started. I turned down parts and they blacklisted me… Then Paramount tried to squeeze me out of my contract and take me for everything I was worth financially and my marriage was breaking up… The press attacked me viciously at every opportunity. I came very close to suicide.” (Carroll Baker in a 1977 interview as quoted in The Los Angeles Times, January 3, 1987)

The disastrous Harlow became an infamous box office bomb, a career-stalling disaster that was complicated by Levine pulling out all the stops to completely trash Baker’s career. Take for example this entertainment article, allegedly planted by Levine, graphically detailing how her husband happily showed their six-year-old son nude photos of Baker. It should be noted that Levine had talked Baker into the nude photo shoots in the first place — nude in the 1967 Playboy sense, mind, which would be tame stuff nowadays, but doesn’t excuse Levine’s skeevy implications of both pederasty and Oedipal issues, nor does it explain the entertainment media who dutifully spread these rumors on his behalf.

Unsurprisingly, Baker was unable to find work after Harlow, except a brief cameo as herself in 1967’s Jack of Diamonds. Later that same year, finally out from under Levine, she dumped her husband and fled to Europe. It was at the Venice Film Festival in 1967 that she discovered a host of Italian directors eager to work with her. Other American actors were enjoying solid careers in Italy at the time, and Baker saw no reason she couldn’t as well. After a couple of lackluster efforts, she teamed up with Umberto Lenzi for what would be a trilogy of erotic thrillers in the giallo style.

Umberto Lenzi is probably best known for gruesome, explicitly violent cannibal films such as Eaten Alive (1980) and Cannibal Ferox (1981). After getting his start in low-budget adventure films, Lenzi began to make a name for himself in the mid 1960s with Eurospy flicks, eventually moving on to the giallo genre. His gialli were never met with the same enthusiasm as those from his contemporaries such as Mario Bava or Dario Argento, and in many ways his films are more straightforward exploitation rather than full-blown gialli. Lenzi was influenced by Hitchcock, of course — nearly every giallo film is — but there is also a strong influence from French films noir in his work.

Orgasmo (1969; American title Paranoia) is one such film, with a few Hitch references mixed throughout a plot obviously inspired by Les Diaboliques (1955). Orgasmo was the first of three films Lenzi made with Carroll Baker in the lead, and is often confused with the third film of the series: The American version of the 1969 Lenzi-Baker film was known as Paranoia, while the Italian version of their 1970 film was also known as Paranoia. A little breakdown of the trilogy is in order, to keep things clear:

1) Orgasmo (Italian title) / Paranoia (American title), first released February, 1969

2) So Sweet… So Perverse (same title in both Italy and America), released October, 1969

3) A Quiet Place to Kill (American title) / Paranoia (Italian title), released February, 1970

Most sources say that distributors deliberately named the 1970 film Paranoia for the Italian release in an effort to capitalize on the success of the earlier film. It should be noted that many films were released in Italy with titles that implied a connection to American films they did not actually have; for instance, Lenzi’s Ghosthouse (1988) was released as La casa 3 in Italy, in an effort to imply it was part of the Sam Raimi Evil Dead series, which had been released as La casa and La casa 2 in Italy.

In Orgasmo, Carroll Baker plays Kathryn West, a beautiful American widow who has come to the Italian countryside to recover from her husband’s death and escape the tabloids. Formerly a popular singer — the details are only vaguely alluded to, but she was presumably a pop star a la Petula Clark or Dusty Springfield — Kathryn had retired from the biz to marry an older, wealthy man. His sudden death in a freak car accident had put her back in the tabloids and at the mercy of his crabby relatives. Kathryn relies on her trusty attorney Brion (Tino Carraro) to help her navigate through the mess.

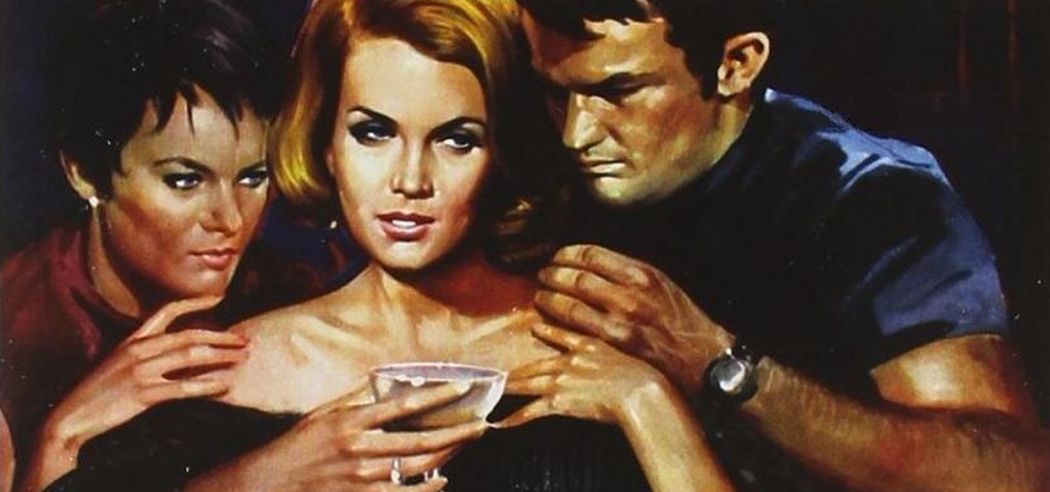

Soon after moving into her large, luxurious and mostly empty estate, the car of young American Peter Donovan (Lou Castel) breaks down at her gate, and the cheeky kid invites himself in. Thus the suspense begins, and Orgasmo settles into its horny widow/May-December romance/trippy youth culture tropes that turn this film into the campy laugh riot that makes it so fun to watch. Some of this fun is diminished by the appearance of Peter’s alleged sister Eva (Colette Descombes), who is beautiful in the popular ultra-mod way Lenzi clearly was looking for, but the actress lacks any substance or talent, and the film begins to bog down.

Some of this cinematic bog is thanks to a plot that strains credulity, not so much in the nefarious doings of people out to get Kathryn, but with the ages of the characters. Castel is not astonishingly younger than Baker — he was 25 at the time of filming and looked nearly 30, while she was 37 and looked… nearly 30. Castel can’t manage to act like a precocious 20-year-old, though Baker at least attempts to behave like the 40-something widow she’s supposed to be. But the film often approaches this age discrepancy in bad faith, having Kathryn call Peter and Eva “youngsters,” and putting her in clothes meant for much older women. The worst case of this is when the siblings take Kathryn to a dance, and Kathryn is dressed up like your grandma at your aunt’s 1972 wedding, held at St. Bob’s Episcopalian Church in downtown Cleveland.

Notice Kathryn’s shiny little bauble in her hair? That’s another bad-faith move on the part of Lenzi, an unsubtle reminder that Kathryn is supposed to be a jet-setting rich bitch who deserves a comeuppance simply because of her wealth. Peter’s protests against her wealth are too vague to be of much use, but he appears to regard her as stereotypical bourgeoisie. For whatever reason, the film doesn’t manage to portray her as a purveyor of conspicuous consumption, except for the moment we see her at a teen dance with diamonds in her hair. Her rented estate is large but thinly furnished, her clothing isn’t extravagant, and we don’t see her traveling the world for pleasure, only stressful, upsetting business that she actively tries to avoid.

It’s possible some of this is simply due to the budget constraints of the film, that we’re meant to take large inheritance plus renting a villa plus shiny doodads in her hair as the equivalent of bourgeois decadence. Kathryn is also portrayed as philosophically and sexually timid, a conformist unaware of how the so-called other half lives and loves. Again, though, this is presented in a clumsy manner, with Peter and his alleged sister seducing Kathryn by suggesting a menage a trois, and Kathryn, former famous pop singer, acting as though she had never heard of such a thing.

Despite these weak justifications within the film, Kathryn is still a satisfactory modern example of Weberian Stratification. Her bourgeois wealth is gained through the inheritance, and her prestige signified through her popularity in the culture and tabloid media. But where, then, is the third strata, her desire for power? Kathryn just wants to be left alone. She has no plans for resuming her career, wants the media kept completely away from her, never has parties, tells her lawyer to just give her late husband’s estate home back to his family for free. These are hardly the actions of a woman striving for some social position or power.

And we in the audience feel sympathy for her, the lonely widow stuck in a house with two kids playing on her insecurities about her age and plying her with booze and drugs. At the same time, we also see how Kathryn acts toward her maid Therese (Lilla Brignone); she’s very sharp and demanding, in one scene casually expecting the maid to bring out tons of food that she never had any intention of eating. As the old saying goes, you can always tell someone’s character by how they treat service workers. There’s a subtle layer of artistic complaint in Kathryn’s boorishness toward Theresa, too: her treatment of her servant mimics the way studios treat their actors, something Carroll Baker must have keenly felt after her ordeal with Levine.

Still, the power trip she gets by ordering Therese, and attempting to order the “youngsters” Eva and Peter around, doesn’t quite add up to the kind of bourgeois desire for power philosopher Max Weber defined in his stratification theory. No, we only get one moment where Kathryn lets her bourgeois freak flag fly, when she takes a brief trip into town and literally gets off on slumming with the plebes… until they irritate her by their existence and demand for what is rightfully theirs, and she throws money at a couple of them and drives off in a huff. That’s easily explained away as temperament until the finale, a twist ending that reveals things about Kathryn that re-tint everything we have just watched her do over the previous 90 minutes. It’s a really clever shock in that it upends our sympathies, and finally completes the sociopolitical commentary Lenzi had been striving for.

Not that Lenzi strove for all that much beyond salaciousness with his film, mind you. Orgasmo plays more like the American erotic thrillers so popular in the 1980s and 1990s than a true giallo. The sleazy mystery at the heart of Orgasmo is pure giallo — the word meaning “yellow,” a reference to the covers of popular pulp mysteries of the late 1920s on — as is its criticism of women, especially women of wealth. There’s often a frustrating double standard in gialli, movies that use the sexuality of their female leads as the primary advertising point, while condemning the female characters they play for being too sexual. In Orgasmo, this condemnation mirrors heavily the “woman of 40” trope so popular in pulp novels, the stereotype of a woman hitting her sexual peak while at the same time, in the more sexist plots, desperate for one last sexual fling in the face of the unspoken threat of menopause.

There is also a determined effort to force the audience to judge characters based on their looks; Therese is meant to be suspicious, for example, not because she does anything strange or concerning — writing a multi-layered character would take effort, you know. Instead, the actress is made up to be dowdy and given unflattering close-ups and told to glower all the time, and you wait for her to get all Mrs. Danvers, but it never happens. It’s interesting to note Roger Ebert’s original 1969 review of Orgasmo (under the Paranoia title) not only focused more on a previous unrelated release, Succubus (1969), but groused about movies where “even the girl was ugly” and how “the Chicago proletariat” likes bad films. What does one even do with a review that commits the same sins as the movie it pans?

Orgasmo was available for years only in a sub-par print that edited out the trippy menage a trois scene, infamous for its clumsy metaphors involving pussy cats and statuary of mythical creatures with their tongues hanging out. The scene has now been restored in the Region 2 DVD releases, but unfortunately the DVDs only come with an Italian soundtrack with English subtitles. While I usually prefer the original soundtracks, in the case of Orgasmo, the English release was overdubbed with many of the original actor’s voices, and missing that voice track means missing Carroll Baker’s whining drone, which is half of the fun of the film.

As Alexia Kannas writes at Senses of Cinema, “there is rarely a full sense of narrative closure at the end of a giallo film.” Orgasmo is one of those rare examples, with its trick ending followed by another shock ending followed by a third shock, all of which comprise full and complete narrative closure, so extreme it becomes comedic.

This sort of lazy storytelling permeates Orgasmo, and is the most responsible for the film’s insubstantial feel. One can’t go into the film expecting true, classic giallo without being disappointed, but when approached as a campy 60s throwback, Orgasmo can be a whole lot of fun. It’s bright, colorful, soapy and silly, with just enough depth in the right places to keep you interested. This is one of the lightest, fluffiest gialli you will ever see.

***

Other Sources Not Linked Above:

Italian Cinema: Arthouse to Exploitation, Barry Forshaw

Italian Crime Filmography, 1968-1980, Roberto Curti

Sounds interesting. I’ll have to check this one out. Your final paragraph, in particular, makes it sound like the Lenzi movie I watched for this year’s blogathon: Spasmo. Not overly lurid, more interested in establishing its mystery, harmless enough, yet still contains some of those not-so-great illogical giallo moments that keep it from being great.

Thanks for this entry, Stacia!

Hi Kevin! Sorry I didn’t reply sooner, my internet has been off and on for days (first it was my modem, then it was some sort of infrastructure breakdown in town). You’re right in that gialli tend to just go off the rails with some illogical, cheesy moments that hinder more than anything, but I have to think that must have drawn people into the theaters, too.

Thanks so much for hosting the ‘thon! It’s been great as always!

Pingback: Warner Archive Grab Bag #2: Camp Edition - She Blogged By Night