The Congress

★★★☆☆

Director: Ari Folman

Drafthouse Films (Official Site)

122 Minutes

Now Available on iTunes and On Demand | In Theaters August 29, 2014

–

“Lousy choices,” Al tells his client. “That’s your whole story.” Al (Harvey Keitel) is agent and frustrated father figure to Robin Wright (playing a riff on herself) who, as Al reminds her, has only one last chance at big screen success. Miramount Pictures is giving her that one chance, but as she discovers when she meets with the studio president (Danny Huston), they don’t want her to play a role: they want to scan her. Miramount tells her this is her last chance, that everyone will be storing their likenesses and talent in studio computers, and if she passes this up she’ll never appear on screen again. And the beauty of this system, she is told, is that they no longer have to worry about her aging, her needs, or that pesky thing called free will.

The Congress, the new film by Ari Folman, treats this astounding offer as simply the next step in where we are already headed, and is probably right to do so. After all, nearly 20 years ago, computers resurrected Fred Astaire so he could dance with a vacuum cleaner; just two years ago, computers shaved a decade or more off the entire cast of The Hobbit (2012). It’s not just that we have the technology to do these things, but that audiences, wanting both the reassurance of well-known faces and plenty of new commercial art-product, demand it.

The first half of The Congress is live action, with Wright giving a terrific performance from a script that mirrors her own life and hits close to the bone. She struggles with past decisions, uncaring studios and a son (Kodi Smit-McPhee) who suffers from the slow degeneration of his sight and hearing, yet possesses the ability to turn the small amount of sensory information he does receive into something altogether new. He’s a harbinger of the future according to his doctor (Paul Giamatti), who predicts we will eventually all learn to take tiny sensory signals and turn them into a new reality.

It’s a fine, moving meditation on the state of commercial art, on big businesses turning both art and humanity into a commodity, on aging and finding our place in the world and the illusion of choice. A stand-out scene with Keitel talking Wright through the scanning process hits all the right notes, a cathartic, final moment of reality before the film fades out and returns, 20 years in the future, as a long-retired Wright travels to speak at Miramount’s Future Congress. This Congress is held in a mandatory animated zone, where the animation is actually the product of one’s own mind after the ingestion of a synthetic hallucinogen.

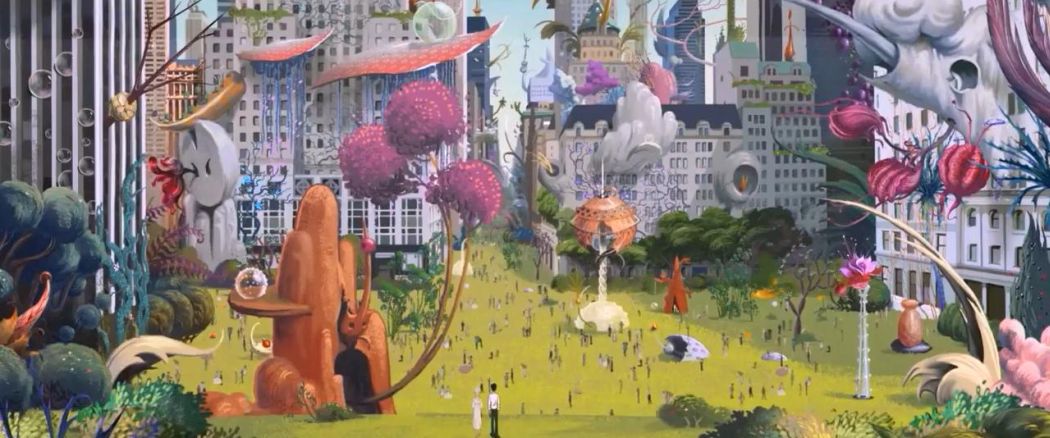

Though visually entertaining and with exceptional background art, the rules of this animated world in the second half of the film completely crumble under even minute inspection. Robin drives along rainbow roads amidst multicolored flying fish for no reason other than they are easily-recognizable psychedelic tropes. This melange of animated stereotypes is pulled from dozens of animated films, such as Heavy Metal (1981), Fritz the Cat (1972), Yellow Submarine (1968), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), “Porky in Wackyland” (1938), and damn near anything that have ever possessed even a single frame of animation. The film’s indulgence in the very aesthetic it condemns is done in part to critique the lack of originality in Hollywood, though The Congress is too satisfied with its own cleverness to really carry it off.

The glacial pace of the animated sequences is another fatal misstep for the film. Done in the style of 1930s Warner Bros. shorts, with rubbery limbs and background characters grinning as they walk by, the slow pacing sucks every last ounce of energy out of the film. The result is a series of lethargic episodes so vaguely imagined that the character of Dylan — a Ronald Colman-Adrian Brody hybrid voiced by Jon Hamm — must have been introduced solely to provide explanatory voiceovers. And explain he does: what happened in the past, what is happening now, and what will happen in the future. Even Hanna-Barbera didn’t slow things down this much.

The background action is occasionally irreverent, if one could call depicting Mohammed or showing a couple of fish fucking irreverent nowadays. Mostly, the world is teeming with those who have opted to ingest whatever drug will turn them into the celebrity of their choosing. The result is an interminable series of goofy cameos, an Elvis here, a Yoko Ono there, all staring straight at us with a knowing look, but the question is: what do they know that anyone who has been even tangentially plugged into our consumer culture doesn’t?

Based on the Stanislaw Lem novel The Futurological Congress, there is little direct comparison between the book and the film. A few animated scenes are based on Lem’s descriptions, but the novel’s examination of a society in flux, of the inevitable combustion between technology and humanity, has been discarded. The Congress eschews nuance, preferring to let itself be consumed by its own cynicism, reducing what could have been a fun ride down to nothing more than a cinematic poke in the ribs.