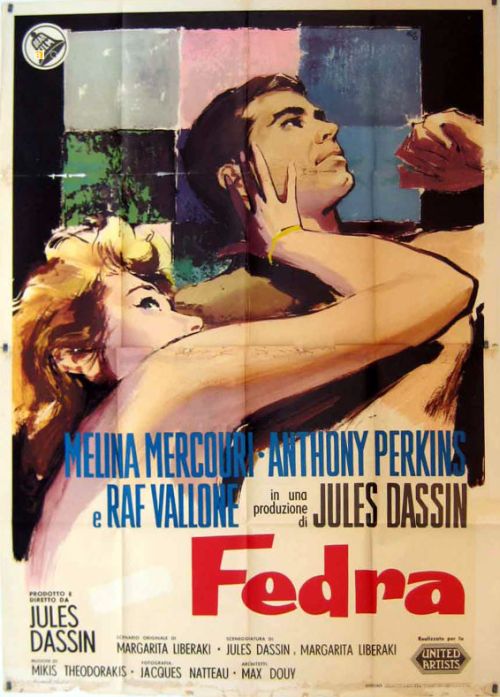

Jules Dassin’s Phaedra (1962) opens with gigantic ships, fireworks, big corporate grins and nasty sideways looks. It’s the ceremonial launching of yet another enormous ship commissioned by Greek shipping magnate Thanos (Raf Vallone), who has dedicated this particular trade-transport leviathan to his beautiful wife Phaedra (Melina Mercouri). After a chat with friends, Thanos discovers that his college-aged son Alexis (Anthony Perkins) may be attending the London School of Business, but his paintings have been featured in art gallery openings, and he’s worried Alexis may turn to art instead of business. Phaedra is dispatched to London to bring her step-son Alexis back home, a chore that doesn’t exactly excite her, as she has met Alexis only once before, in a meeting where the then-teen boy made it clear he loathed her.

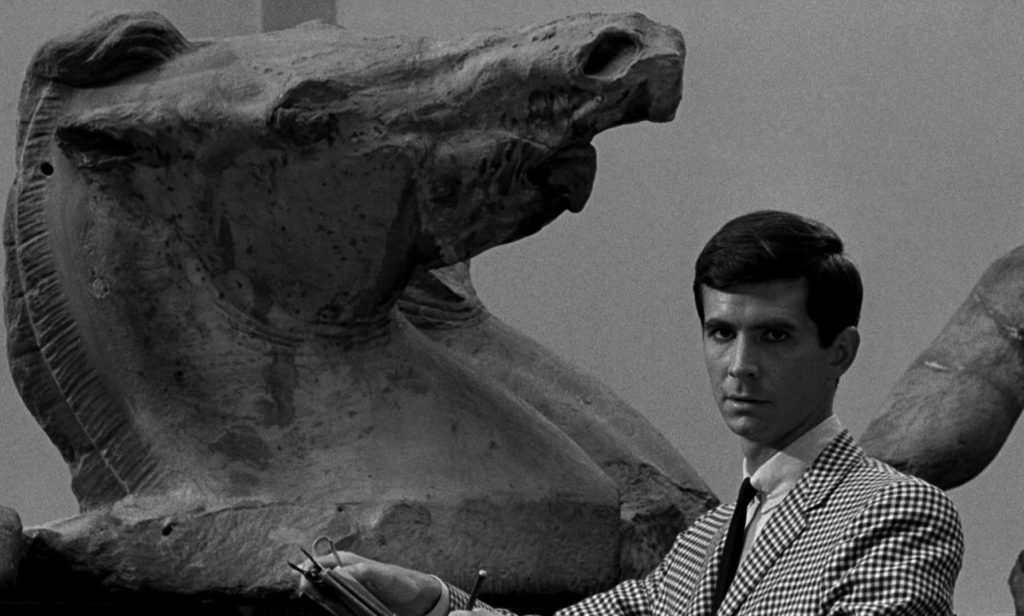

Times have changed, it seems, and they fall for each other the moment they meet in a London museum, and embark on a passionate affair. When Alexis realizes Phaedra is never going to leave Thanos, he breaks off with her, leading to a whirlwind of jealousy and anger that ends with, well, a tragedy.

Dassin takes both his muse and location almost too literally in Phaedra (1962) by indulging in this reworking of the Greek tragedy Hippolytus. Co-written with Margarita Lymberaki, the film concentrates almost entirely on the almost-incest angle while neglecting most of the rest of Euripides’ tale. The incestuous relationship lacks teeth, however, as Alexis and Phaedra have barely met prior to her visit to London; she almost doesn’t recognize him when she arrives, and one never gets the sense of them being related in any way.

James A. Boon in Ethnographica Moralia suggests that the film is meant to memorialize the sex between Phaedra and her step-son, which is only referred to in Hippolytus, rather than the entirety of the myth.

James A. Boon in Ethnographica Moralia suggests that the film is meant to memorialize the sex between Phaedra and her step-son, which is only referred to in Hippolytus, rather than the entirety of the myth.

It’s hard to blame Dassin for lavishing screen time on Melina Mercouri, a fine, charismatic actress and his long-time love, though now is as good a time as any to mention that Dassin was still married to his first wife during filming. The real story in Phaedra, however, isn’t with Phaedra at all, but found in the backgrounds where beautiful Greek antiquities languish in a stark London museum, thousands of miles from their homes. It’s in Alexis’ attentions toward his father Thanos, his attempts to fit into Greek culture, and in Thanos’ corporate greed. Phaedra is the link in all this, the reason, the cause of and solution to many of these larger problems, but she’s too consumed with a tragic fate that she feels is inevitable and which, thanks to a tenuous screenplay, seems to have been invented in her own mind, and for no good reason.

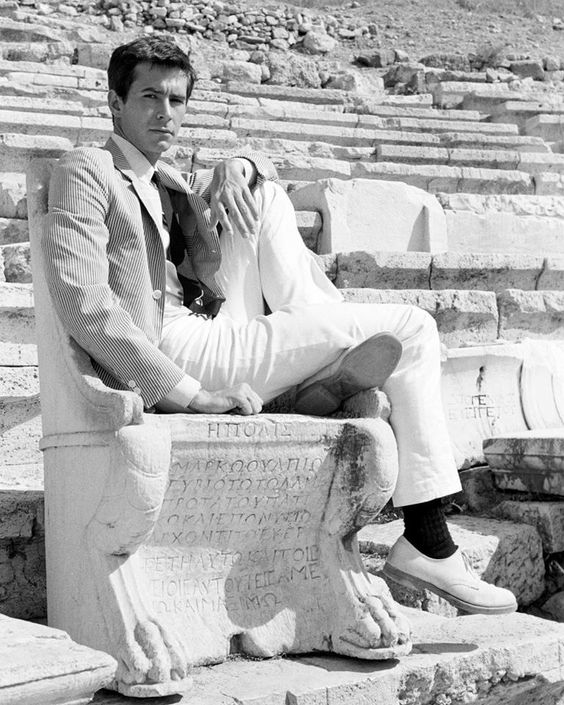

Perkins posing for a publicity shot in a marble seat dating to about 400 AD, at the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, Greece. The noted historian Pausanias in his Description of Greece (c. 140 AD) described the large temple and sanctuary dedicated to Hippolytus in the town of Troezen, located across the gulf from Athens, as including the temple of Aphrodite Calascopia, which stood on the area where the real-life Phaedra was said to have lusted after Hippolytus as he exercised in the stadium below. Phaedra’s tomb was also reported to be in this area, though the ruins in Troezen now consist mostly of the sanctuary and little else.

There’s a rather odd scene early on when Phaedra says she doesn’t want to walk around London in her high heels, so she and Alexis drop into a shoe store where she buys a stylish pair of flats. She remarks on how odd she looks, Alexis agrees, and multiple men stop in the street to give her a strange look because she’s not in heels. My vast research (read: 15 minutes on vintage fashion sites) shows plenty of dressy flats were available for women in 1962, especially in London. Certainly, this scene is supposed to show her tendency to throw caution to the wind, to do things that will make her an outcast, to rebuff tradition, but scenes of this nature rarely work when they are based on such an illogical conceit.

But hey, it’s largely subjective as to what works and what doesn’t, and a scene at the end when Alexis, our revamped Hippolytus, is fleeing the scene of the Greek tragedy, is the scene that most reviewers mention when discussing the flaws in this film. Alexis is ranting and raving out loud to no one, mostly to himself, but also to J.S. Bach, whose Toccata and Fugue is blasting from the radio. It’s a fantastic breakdown yet one I can’t imagine anyone was expecting in 1962; it has the air of a decidedly post-millennium freak-out. The Digital Fix, in their review for the DVD release several years ago, calls it “uncomfortable,” which is maybe a touch harsh, though one does wonder how a man of British and Greek descent, educated in London, could all of a sudden sound like a Midwestern carnival barker.

For my money, the crazed rantings of a young man as he drives a sports car he coveted in the same way a child covets a shiny new toy really works in the film, and Perkins sells the hell out of that scene. For almost everyone else, that scene is their best example of why the film is a flawed entry in Dassin’s oeuvre, and the strange shoe scene that is going to irritate me probably until my dying day doesn’t even register. That’s opinions for ya.

Still, one can hardly argue that Phaedra is almost a parody of the kind of European art-house films that sitcoms and comedians brought up in the 1960s when they wanted to allude to something edgy without getting on the wrong side of the censors. There’s the saucy sex scene, the megalo-romantic dialogue, the shots filmed on location with a million lookie-loos in the background, the wide scenic shots, the sturdy and toothsome male lead, the American actor brought in for box-office appeal, it’s all here. And in that context, it’s a solid piece of entertainment, yet Americans stayed away in droves, as they do, while Europeans loved Phaedra to bits.

Olive Films has released Phaedra on a lovely new Blu-ray with chapters, theatrical trailer and (excellent) English subtitles.