Mild trigger warning for attempted rape/ravishment in the film which is discussed later in this summary.

Mild trigger warning for attempted rape/ravishment in the film which is discussed later in this summary.

Also, spoilers for Where Love Has Gone. Big ones.

***

It occurs that I never announced the winners of the Reader’s Poll: There was a tie between Where Love Has Gone and Lace, so I hope to do both. Lace will be a bit tricky since it’s a miniseries of approximately 93 hours in length, but Where Love Has Gone? That’s an easy one, or so I thought until I started writing this post.

Of the plethora of 1960s mainstream soap-opera-esque campfests, Where Love Has Gone is one of my favorites, right up there with Susan Slade and Valley of the Dolls and, yes, even Peyton Place, which this film mimics in tone and subject matter. There is just so much to say about this film, so many really problematic things to unpack and trashy doin’s to make fun of, that one could go on all day.

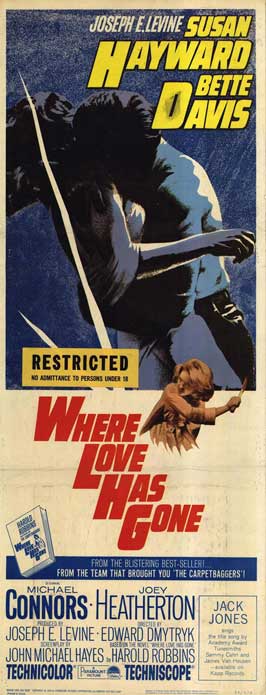

First, the cast of this film is Fab. U. Lous. Bette Davis, Mike Connors and Susan Hayward star, along with Joey Heatherton, Jane Greer, DeForest Kelley, George Macready, Anne Seymour, Whit Bissell, and others. Now, many of these actors are given thankless roles, but it’s great just to see Macready and Greer in any roles later in their careers.

As you can see, this film counts as part of the Bette Davis Project, which I am still doing and will discuss in more detail in October when I do a nice, thorough State of the Blog. Bette looks terrific in this film, both in the 1945 flashbacks and the 1964 modern-day scenes, though toward the end when she gets a comeuppance she is made to look older.

And now is as good a time as any to mention my only copy of this film is from an old VHS recording off TCM, as you can clearly see here on ol’ Touch Connors’ back. It’s not an optimal way to view this film, since the pan ‘n’ scan technology is almost as old as the film itself, resulting in some accidental hilarity and a lot of shots of people’s noses with a wide expanse of blank set wall behind them.

Where Love Has Gone rips off Peyton Place in its soap operatic tone, and is very obviously based on the murder of Peyton Place star Lana Turner’s boyfriend. It’s incredibly trashy, and while I usually save that adjective for John Waters flicks, Where Love Has Gone earned the moniker. It has earned the hell out of it.

We open with shrieks and screams from Valerie Hayden (Susan Hayward) and her daughter Danielle (Joey Heatherton), then a bloody sculptor’s chisel falls to the floor. Luke Miller (Mike “Touch” Connors), in another town, is interrupted at a business meeting to be told the news: Danielle has murdered her mother’s boyfriend. Luke rushes to see her and we find out he and Valerie have been divorced for years, and he has had no contact with his 15-year-old daughter per Valerie’s demands. Valerie’s lawyer explains Luke is there only for appearances, to make it seem like Danielle has a supportive family.

As for the man who was murdered, he was Valerie’s current boyfriend. Soon we get a taste of the silly dialogue this film is known for, as the lawyer explains the boyfriend “knew nothing about double-entry bookkeeping, but he was a pro at double-entry housekeeping.”

…What? Is that some kind of entendre about double penetration, or about the man diddling both Valerie and her teenage daughter? Either way, this classy, classy dialogue is just the kind of thing you’re gonna get through the whole damn film. So put on your snorkels, kids, we’re goin’ under.

Valerie won’t get her lazy butt out of bed to answer the phone even though her daughter is being sent to juvie that very morning, so instead she turns off the phone, grabs some smokes and yells for an aspirin. There is nothing likeable about Valerie at this point, and when her mother Mrs. Hayden (Bette Davis) scolds her, that seems both deserved and logical.

Luke, the lawyer, Valerie, Danielle — pronounced Danny-Ell for maximum irritation — gather at Mrs. Hayden’s manse, exchange unpleasantries and head out to juvenile hall, all the while no one is particularly bothered that a man has just been murdered.

Mrs. Hayden lives in this San Francisco mansion that I am almost positive was seen thirty years earlier in the Bette flick Fog Over Frisco. Someone at the time said this was the Spreckles Mansion, though I don’t think it is. Moira Finnie mentioned this was a Telegraph Hill mansion a few days ago, though I’ve seen others claim it’s a home on Nob Hill.

Joey Heatherton is about as appealing as a day-old banana peel left in the sun, though I understand she has quite a cult following precisely because of this particular performance. She has the second most irritating voice in films (the first being poor Janet Gaynor in her earliest talkies) and every single line she utters, regardless of topic, has the word “Daddy” in it, which she pronounces as a high angry-nasal “dah-dee?” that makes you dream of living in an ancient culture that sacrificed its citizens to appease gods both real and imagined.

Heatherton’s beady little eyes, made more weasely by too much trashy eye makeup, glower at everything and everybody, no exceptions. Some of her line readings are accidentally comedic, especially when she adds inappropriate inflections just for the sake of having an inflection. And she scowls.

After Danny-Ell is safely ensconced in her tiny juvie cell, a flashback to how we got to this horrible, tragic, yet ultimately hilarious day begins. The flashback is supposed to be during WWII circa 1945, yet no attempt to make anyone look different than they do in 1964 is made. Hayward’s hair remains the same throughout no matter what year she is in, as do her fashions.

This is 1945. You can tell because big poufy hair and avocado green suede jackets were totally in back then.

This is 1945. You can tell because big poufy hair and avocado green suede jackets were totally in back then.

In one sad attempt to be period appropriate, this truly horrible drop-waist thing that’s supposed to be a glamourous 1945 gown was born:

It’s the wrong style, and it looks as though it was basted together about 30 seconds before the cameras rolled, with an uneven collar and half-finished white satin skirt attached to a velvet bodice that I’m reasonably certain was sewn on because no one had any time to sew on a zipper or some buttons.

The dialogue is classic, just classic. During the flashback we see Valerie and Luke meet at an art show, she a successful sculptor and he the recently-returned conquering hero. Valerie’s mother Mrs. Hayden invites Luke to dinner at their mansion that night, and after Valerie leaves the room drops a bombshell: She wants Luke to marry her daughter. No reason, really, other than a stable man and hero to the public would be good for the Hayden family image.

Valerie, who hasn’t been impressed with Luke before, is delighted to hear Luke tell Mrs. Hayden off: “If you were younger, I’d turn you over my unrefined knee and spank your aristocratic behind!”

Not only is Valerie basically turned on by Luke wanting to spank her mother, but this line of super classy dialogue has obviously been dubbed in during post production, a trashy afterthought to an already suspect plot.

More delightful dialogue includes the observation that tampering with the results of an art show award is like “bowling with hand grenades.” If that metaphor isn’t deep enough for you, how about when Sam Corwin (DeForest Kelley) declares, “I’m as practical as a can opener!” to Valerie, who smiles and replies, “Don’t try to spoil my honeymoon.”

Does it make sense? No. No, it does not, yet people said it, it was put on film, and we watch it.

Edward Dmytryk, Bette Davis and Susan Hayward on the set of Where Love Has Gone.

Edward Dmytryk, Bette Davis and Susan Hayward on the set of Where Love Has Gone.

Speaking of Corwin, this character is all over the place. The film attempts to code him as a gay man but in the same sentence will portray him as a lech who bones Valerie every chance he gets. He’s unmarried, unscrupulous, and always speaking with a pipe in his mouth, which is a low-rent version of Cairo’s walking stick in Maltese Falcon, plus it makes Kelley difficult to understand which seems counterproductive to film making, but I am not a scientist. Perhaps I do not understand the basic geometrical chemistry involved in cinematic pipes.

Throughout the film, comments are made about Corwin not knowing what a real man is. He is seen looking at the crotches of Valerie’s male nude sculptures, and Mrs. Hayden says she doesn’t approve of Corwin’s private life. But then Valerie and Corwin not only flirt but apparently rut like weasels on occasion. Nobody was paying attention to this character! It’s a good character, too. Why didn’t anyone even try some continuity? Continuity is free! It’s a renewable resource! There is no excuse, movie. None.

So, about Valerie’s nudes. After she and Luke marry, Mrs. Hayden sabotages his plans to go into business himself, so he is forced to work at the Hayden family corporation. Valerie gets petulant about this — her entire character is about rebelling against dear old mom, which is a pretty sad thing for a woman in her late 40s — and the marriage breaks down. Luke can’t hold his drink and Valerie can’t be faithful, her art being dependent on an active and anonymous sex life. After Luke overindulges during a business party, Valerie storms off to one of her old haunts.

One of her old sex-ational haunts. Here she picks up men, bones them and then sculpts their nude bodies into art the United Nations commissions for its lobbies. Mostly true story. In a particularly tacky scene, Corwin praises her for her artistic gifts returning while gazing approvingly at about three dozen male nude sculptures scattered about her studio, while Valerie adds more and more clay to the crotch of the current nude she is working on. Making something larger, I presume. It’s all very tasteful.

I stole this screengrab from some lucky bastard who has this film in the proper aspect ratio.

I stole this screengrab from some lucky bastard who has this film in the proper aspect ratio.

Both Luke and Valerie are complete immature fuckwits when the marriage starts to go south. He drinks, she fucks around, then shrieks and growls and howls at him for being drunk even though she is slurring her words and stumbling like she just drank half a bottle of Orin Swift’s Machete. It’s never played as hypocrisy though, but rather the opposite, and I admit I have thought more than once that perhaps Hayward was drunk but the character Valerie was not supposed to be. The growling and general unpleasantness are most certainly all Miss Hayward’s, so perhaps the booze was, too.

A particularly hilarious scene happens during one of the marital spats. Touch Connors apparently doesn’t know how to pour himself a drink, because as he sits down with coffee at the breakfast table, you can see he has filled his cup to near overflowing. As he gets upset, he slams his hand on the table and the cup flips over, a huge puddle of coffee spilling everywhere. Touch rights it quickly and looks back at Hayward to try to save the scene, but there’s an unmistakeable look of, “Dammit!” in his eyes; meanwhile, she flusters a bit and almost starts to laugh, makes an ad lib about spilling the coffee, to which he says, “To hell with the coffee!” and the scene continues. It’s not a horrible bit of ad lib, but it was obviously not planned, as immediately after the coffee spill there is no huge brown puddle seeping all over the place.

On the left pic, a huge coffee spill, bottom right. On the right pic 8 seconds later, the spill is gone, replaced by a plate of delicious toast.

On the left pic, a huge coffee spill, bottom right. On the right pic 8 seconds later, the spill is gone, replaced by a plate of delicious toast.

And now, the punchline: When he gets up from the table after Valerie has stormed off, he fills his grapefruit juice up with some vodka, again overfilling it. Connors panics, tries to drink it quickly but still spills it on a prop briefcase that ends up flying across the room when Connors finally loses his temper.

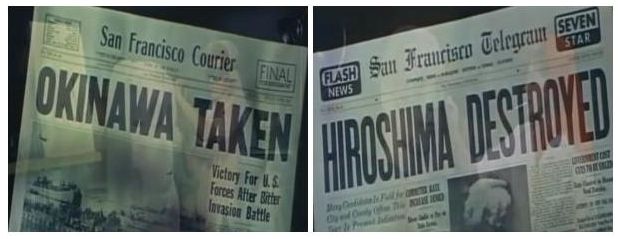

Speaking of decorum and lack thereof, a particularly tasteless and confusing scene occurs when Valerie is waiting for her husband as he serves in the war. Headlines about the destruction of Japan and deaths of an estimated 225,000 civilians are superimposed over scenes of Valerie smoking cigarettes and sculpting male nudes in a frenzy.

What does this even mean? Anyone? “Time passes while people are vaporized and also art” is the best I can come up with.

What does this even mean? Anyone? “Time passes while people are vaporized and also art” is the best I can come up with.

When the marriage falls apart, Luke attempts to force himself on Valerie because her body is his right or something — your basic stupid excuse for marital rape that was common back then — and she tells him to go ahead and do it. Valerie reminds him that he once told her he didn’t like to stand in line, but standing in line is exactly what he is doing now because he’s not the first person she’s boned that day. It’s scandalous and tacky, of course, but also gross on a basic germ level. While I’m sure Luke knew all about putting it on before putting it in, I get the impression Valerie wasn’t the kind of lady to carry a pro in her purse.

I would very much like to believe Where Love Has Gone was intentionally showing Luke and Valerie as a couple of damn idiots, though I cannot believe that because it’s simply not true. It’s lazy storytelling, just a series of scandalous shouting matches and upsetting behavior. Also lazy is that the little girl Danielle, the one we’re supposed to care so much about, is only once mentioned in the flashback sequences and never even seen after being baptized. If you don’t see Danielle during the formative years then you don’t get a sense of why she grew up to be such a screwed-up kid.

We return from the flashback to find Danielle is basically let off, her murder judged as justifiable homicide, but again this is a lazy film so it never explains why. And she’s still in juvie, allegedly for psychological testing. The psychologist bribes the petulant, squinty Danielle with cigarettes to get her to talk (professional!) while the social worker, Miss Spicer (Jane Greer), glowers at Valerie for being a single woman who likes to have sex and who works hard at her career.

See, what you need to know is that the evil in this film is motherhood. Mrs. Hayden was apparently cold and controlling toward Valerie, turning her into a sex-crazed, petulant ball of anger. Valerie in turn was too permissive with her daughter, and refused to let her husband — an alcoholic who had, to be fair, just tried to rape her — see his daughter. The film repeats constantly, literally dozens of times, that Danielle became a slut because she didn’t have a father. There’s a real Philadelphia Story psychology going on when Valerie guilt trips Luke by saying that Danielle wrote pornographic letters to Valerie’s now-dead boyfriend because she didn’t have her own father to write letters to.

Where Love Has Gone probably never meant to be political; it was made in 1964 and I’m willing to give it the benefit of the doubt that this is a combination of cluelessness and pop pseudo-Freudian psychology. Someone involved in the film really believed it was just common sense that girls would become psycho nymphomaniac whores if their dads were not around or if their mothers were too controlling.

But you can’t talk about a film like this without talking about politics. In an attempt to be both scandalous and very moral, a series of improbable legal decisions and questionable psychological practices are deployed, all in the name of what today would be called “men’s rights.” The real victim in this film is Luke, who never has any serious consequences to pay for his alcoholism or his attempted rape, who was always held back by women and not allowed to succeed until he extricated himself from the clutches of the evil evil women.

The murdered boyfriend, obviously sleeping with a 15-year-old girl, is never even once held responsible for his actions; he was clearly a man in a position of power over a troubled underage girl, took advantage of the situation, yet no one thinks to blame him. When Luke says if the man was still alive he’d kill him himself, the social worker talks him down.

Susan Hayward during shooting of Where Love Has Gone. Photo courtesy Stirred, Straight Up, With a Twist

Susan Hayward during shooting of Where Love Has Gone. Photo courtesy Stirred, Straight Up, With a Twist

The blame is always squarely leveled at the women, usually by other women… usually by the same social worker who didn’t think it was right to be violently angry at a man who had taken advantage of a 15-year-old girl. Of the three generations of Hayden women, each is on a path to destroy herself, a path paved with her independence. The more a Hayden woman is in control of her own life and body, the higher price she must pay.

And Valerie pays a hell of a price. After telling the truth at Danielle’s trial about what happened the night her boyfriend was killed — and yes, that does mean Danielle’s murder was ruled justifiable homicide before the authorities knew the full truth of the night — Valerie leaves the courthouse in tears. The truth of that night was Danielle was trying to kill Valerie, not the boyfriend, and Valerie herself believes she deserved to die for her actions.

She runs out of the courthouse in tears, and you know some heavy shit’s about to go down because they drag out the Vaseline lens for the rest of the act. Valerie runs home, slashes a portrait of her mother, and then kills herself by stabbing herself repeatedly with her sculptor’s chisel, the same one that killed her boyfriend.

Not only is this a melodramatic end and a hell of a moralistic judgment on a woman who had faults but, really, wasn’t guilty of much besides having an active sex life, it’s also a judgment on Lana Turner. Yes, on Lana Turner, an actress who wasn’t even in this film but who is so very obviously the inspiration for it.

You can’t not make the comparisons between Valerie and Lana Turner, between Danielle and Cheryl Turner, between the fictional crime and the murder of Johnny Stompanato. The ethics of using someone’s real life is in question, of course, though it’s been said that Turner purposely milked the publicity of the trial to revive a stalled career.

Though I don’t think in any way Lana Turner deserved to be treated the way she was by association. Valerie kills herself in a manner we have been told is painful and slow, to atone for her so-called sins, and the film, by so clearly saying Valerie is Lana Turner, is inadvertently placing the same judgment on her.

It’s an uncomfortable situation, one I wrestle with at times when I happen to be critiquing something that involves performers who are still with us. And I have a personal distaste for fanfic of real people (as opposed to characters), and Where Love Has Gone is nothing if it’s not proto-fanfic. At some point — and I submit I am not in the least qualified to determine at what point — it is no longer ethical to use even a celebrity’s private life for art or criticism in any form. But I do think Where Love Has Gone goes beyond that point.

Still, this bad movie is both fun to watch and horrifying to think about; it’s a movie that is very, very concerned with a 15-year-old girl’s hymen, for god’s sake. You have to laugh at it or, at the least, hate watch the hell out of it, otherwise you’ll start writing screeds about privacy issues and art and… oh.

The conclusion of the film leaves me cold every time, not merely for the morality the film pushes but because it says, by association, that Lana Turner deserved to die, that Cheryl Turner was a psychosexually disturbed murderer, that they all just needed men in their lives to control their renegade vaginas that get them into all kinds of trouble. So it’s easy to hate the film, but then I remember that DeForest Kelley is as practical as a can opener, which is something that might ruin Susan Hayward’s honeymoon, and I kind of love the damn thing all over again.

but then I remember that DeForest Kelley is as practical as a can opener, which is something that might ruin Susan Hayward’s honeymoon, and I kind of love the damn thing all over again

“Damnit, Jim–I’m a doctor, not a can opener!” I would now like to present you with the Cinematic Medal of Honor, for being brave enough to sit through this multiple times in order to mock it for our pleasure and delight.

I don’t know why I like this movie. My post was probably 50% me trying to talk myself OUT of liking it, but I still do.

Pingback: Camp & Cult Blogathon: Lace (1984) » She Blogged By Night