A lot of people for a lot of years tried to make Johnny Mack Brown happen. The handsome All-American halfback-turned-actor cut his teeth on a few silent films before being cast as the ostensible male lead in Our Dancing Daughters (1928), with Joan Crawford, Dorothy Sebastian and Anita Page originating a trio of what would become iconic roles, first as flappers in Dancing Daughters but then, as the Depression set in, department store girls sharing a New York apartment together. Our Dancing Daughters was a great hit, and Brown was groomed by MGM to be a leading man.

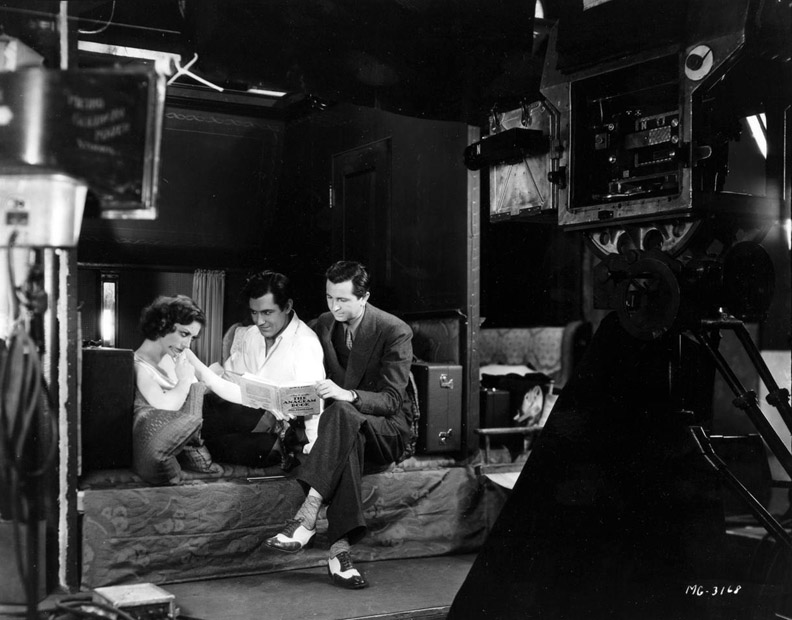

Crawford, Brown and director Malcolm St. Clair during filming.

Crawford, Brown and director Malcolm St. Clair during filming.

Brown was soon cast in Coquette (1929) as Mary Pickford’s love interest — she would go on to win an Oscar for the film — and Brown was cast in few other A-list films, too. His leading man status didn’t last, and he quickly ended up in smaller-budget programmers like 1930’s Montana Moon. One of the many ill-conceived films that came out of the early talkie era, Montana Moon was once described by its leading lady as “a bit of fluff that was supposed to help Johnny Mack Brown, but I think it hurt him instead.” Brown’s career was indeed headed straight to B-movie Westerns, while Crawford’s star was still on the rise.

In Montana Moon, Joan Crawford is — get this — “Joan,” a wacky socialite who runs around the country with willful abandon. The film opens with Joan nearly missing a train carrying her sister, played by Dorothy Sebastian, another Dancing Daughters co-star, and her sister’s cad of a fiance, Ricardo Cortez.

Cortez as Jeff, happy to help Joan up onto the train.

Cortez as Jeff, happy to help Joan up onto the train.

When Jeff makes an inappropriate advance toward Joan, she hops off the train near a tiny town in the middle of the night, undetected, and just happens to walk to a small campfire near the station where cowboy Larry (Mack Brown) is camping for the night. They talk, and talk, and talk some more, then talk again, and pose in very dated silent-era ways, typical for an early talkie but creaky nonetheless. She and Larry hang around with his cowboy pals for a day or so, decide to get married, then Benny Rubin makes some Jewish jokes, cowboys hit on socialites at Joan’s parties, and Cliff Edwards plays the ukulele while the ostensible conflict gets resolved.

There are some nice moments, and if you like Crawford or Cliff Edwards, this is probably worth a gander. Joan is just on the edge of becoming a solid actress, after floundering a bit during the silent-to-talkie transition, and it’s an interesting watch in that respect. If you’re looking for an example of Crawford’s obvious hard work and dedication to both her craft and her image, this is a great place to start; in moments, she’s a fine actress, in other moments, she’s looking at the camera like a newbie.

As early talkies go, however, the film is mostly a dud, though you could see the very early beginnings of what would become MGM’s pre-Code style. Never as gritty as Warners or as ribald as RKO, MGM developed a more subtle, cleaner tone for their pre-Codes. Made a year or two later, Montana Moon would probably have been a delight.

Everything you could ever want to know about Montana Moon is here, at Legendary Joan Crawford!

—

Count Armalia (George Zucco) decides, as so many counts do, to get drunk and go slumming, deliberately looking for the seediest cafe in Trieste. Stumbling into the Cordellera, the bar owner, having dealt with his type before, assures the count that it is indeed a veritable scumhole. A jaded, Dietrich-esque singer named Anni (Joan Crawford) takes the stage, sings about life being horrible, as one does, and as she finishes, the owner takes her to the count’s table by his request. She’s unimpressed and hardly notices him, until he announces that he has decided to give her two weeks in an exclusive resort in the Alps, money, fashions and even his own reputation, to see if she can pass as high society.

Being overwhelmed with ennui and all, Anni accepts. At the shops the count sends her to, she purchases a gorgeous, expensive, beaded red dress — it can be seen here in a recent photo from the Victoria and Albert Museum, where it’s currently on display — to wear at the resort. Fortunately, she runs into a maid at the hotel whom she used to work with, and is told there will be no event where such a dress is appropriate. To wear such a thing would mark her as classless and out of her league.

Gorgeous Gailbraith sketch of the proposed red dress for the film. This and more about the movie can be found at Legendary Joan Crawford.

More lessons in social graces are to come as she attracts the attention of two men, Rudi (Robert Young), a wealthy gadabout who already has a lovely fiancee, and Guilio (Franchot Tone), the town’s postmaster and Joan’s real-life husband at the time. It was one of several films Crawford and Tone made together, their marriage and romance providing plenty of publicity for the studio. But Tone was reportedly unhappy by the treatment he got at the studio, and later, Joan would say of Tone, “Sensitive husbands don’t like second billing.” No more films with her husband would be forthcoming, and soon, they would be divorced.

Director Dorothy Arzner complained about the “synthetic and plastic” qualities of the script, and after finishing The Bride Wore Red, she refused the next few she was handed by Louis B. Mayer, resulting in her suspension from the studio; this is often the film that is credited with making Arzner decide to quit the directing biz altogether. Critics mostly loathed the film, and its reported box office was far less than what Joan usually pulled in.

Despite all this, The Bride Wore Red, if you will excuse the pun, wears well. It’s a Joan Crawford glamour vehicle, certainly, but with a distance of nearly 80 years the publicity machine and the paint-by-numbers aspects become fascinating. We’d eviscerate a film of this kind were it released today, but time has made us more forgiving of our past artistic transgressions.

Montana Moon and The Bride Wore Red are available on MOD DVD from Warner Archive.

Pingback: The Big Elsewhere - She Blogged By Night