When the bookish Lina McLaidlaw (Joan Fontaine) meets social gadfly Johnnie (Cary Grant), she’s initially unimpressed. But he’s a handsome man, and her parents are preparing for her to enter into the noble field of spinsterism, and she’s having none of that, so she pursues Johnnie and lands him almost immediately. Knowing her father (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) won’t approve, she sneaks off to elope, then enjoys a whirlwind honeymoon on the continent. Johnnie is bit wild and irresponsible, though — Bosley Crowther in his review called him a “rakehell,” which is just a fantastic word — and soon Lina begins to fear that he’s plotting a series of nasty things in an attempt to get money, the nastiest of these things being a plot to kill her for the life insurance.

If you’ve seen Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion (1941), and you probably have, you know that by the end we discover it was all just a big misunderstanding. Golly! While most people criticize the finale, I personally find it less a bug than a feature. The famously abrupt ending is hardly a happy one, as all the problems that plague Johnnie remain. He has a real commitment to laziness, is prone to deception, chronically immature and pitches an I’m-gonna-hold-my-breath-til-I-die kind of temper tantrum the second he thinks he’s about to have to own up to his copious mistakes. Finding out that he’s bad but not murder-my-wife bad isn’t a cause for celebration.

Just as famous as the odd finale of the film is the fact that the original ending, as written, would have shown Lina’s suspicions to be correct, and to have her drink milk she knows Johnnie has poisoned, in part out of wifely obedience but also to incriminate him in murder and finally stop him. It’s a plausible enough ending, reminiscent of Notorious a few years later, and one everyone seems to wish had been used instead of the ending we got.

I swear I grabbed this screen capture before I saw Blu-ray.com had done the exact same thing.

At some point, the ending of Suspicion was changed, making the film about a neurotic woman and little else — this change is frequently blamed on RKO, though some have suggested Hitch himself decided on the change, to preemptively avoid problems with the studio and audiences unwilling to think of Cary Grant as a sinister murderer. As reviews at the time suggest, it was implausible, even in the sociocultural Stone Age that was the early 1940s, for anyone to have considered Johnnie merely rakish and not outright destructive.

Suspicion (the emotion, not necessarily the film) is a second cousin to conspiracy theories, both being means of interpreting confusing and inconsistent information in a way that makes our brains — or at least the emotional bits of our brains — think we have clarified the issue and brought some semblance of order to our lives. Our basic monkey brains have a tough time dealing with ambiguity and complexity, and when emotions run high, as Lina’s have (always remember that in a Hitchcock film, lust is emotion), it’s easy to start believing the incredible rather than accept that a situation is unknowable.

Denial enters into it too, of course, and it’s interesting here that Lina is more in denial about Johnnie’s potential to hurt himself than the possibility of him being a cold-blooded murderer. Contrast this idea of him as a crafty serial killer with the fact hat we’re shown a Johnnie (note the feminine spelling) who isn’t exactly masculine in the traditional literary (and thus, old-fashioned) sense. He needs to be rescued constantly, which is how Lina meets him, and when we first see him he’s running from mild inconvenience and conflict as though he has no ability to stand up for himself. A photographer moments later tries coaxing a smile out of him as though he were a rookie fashion model, and Johnnie even calls himself a “passionate hairdresser,” as a joke, but also as recognition of the fact that even he knows he is not exactly the World War II-era ideal of a manly man.

The second the General’s portrait makes an appearance, you know the old man’s gonna buy it. Portraits in this era are all about someone dead (or presumed dead) who is still looking down on the living, bringing up memories of the past. One of the nicest touches in the film is when Lina is left her father’s portrait in the will; after the earlier scene where Johnnie asks the portrait for Lina’s hand in marriage and they both realize the real General would disapprove of the match, it’s like that long-ago disapproval coming back to haunt them. No wonder they just shove the portrait behind some furniture… until Lina needs it as a confidante, as her paranoia progresses.

I’ve never fully bought the theory that the only thing wrong with Suspicion is the ending. For one, the performances are subpar for a Hitchcock film. Grant seems like he’s practicing for his upcoming role as Mortimer Brewster (Arsenic and Old Lace was filmed just after Suspicion but not released until 1944), and apparently didn’t enjoy working on the film, and especially did not enjoy working with Fontaine. Bruce can actually be seen mouthing Grant’s lines as he says them — watch in particular the scene after Lina returns to see Johnnie and Binky repairing the radio. Sir Cedric Hardwicke and Dame May Whitty aren’t given much to do, and a lot of the smaller roles of socialites seem to have been cast on whim. Fontaine gives a solid performance, and won the Best Actress Oscar that year, though it was surely a consolation prize for losing for Rebecca the year prior.

And though the visuals in Suspicion are arresting and well done, they are also campy in a way that doesn’t really match the material, not unless you see the film as nothing but one big laugh at a spinster who went hysterical the second she got married and lost her virginity. The shadows that cast webs over the interior of the house are so omnipresent they start to lose their impact — wasn’t it ever dark outside? — and the infamous glowing glass of milk becomes a funny-looking glass of phosphorus by the time the camera holds on it for just a half a second too long.

These grandstanding moments in Hitchcock’s films have often seemed to me like the mark of an insecure artist, someone creating a big flashy thing that will get attention can be publicized, while the riskier and more subtle things can go unnoticed, and you have your little out. You can just say that no one noticed the times you really put your heart into your work because they were looking at that fancy schmancy thing you did over there instead.

With Hitch, if you take what he says at face value — not always a good idea — the flash may also be an indicator of his artistic boredom. He’s also seemed to be the kind of director who never really could (or perhaps never really wanted to) put emotions into his films. He might use them to indulge crushes or play with imagery or wind up audiences or work out his psychosexual issues, but that was about as far as it went with him.

That’s what, at least to me, makes Suspicion so fascinating: it’s that you can tell in the first minutes that Hitch wasn’t buying that this whole scenario was just the product of a hysterical woman. Even Alfred Hitchcock of Rope’s “chicken choking” and North by Northwest’s train going through a tunnel fame wasn’t convinced, and if he wasn’t convinced, we’re not going to be convinced. This turns Suspicion into a (probably inadvertent) commentary on the position women are often put in because they are expected to be submissive and trusting to their husbands, and if their husbands are impossibly handsome, charming men, they’ve got a big problem on their hands.

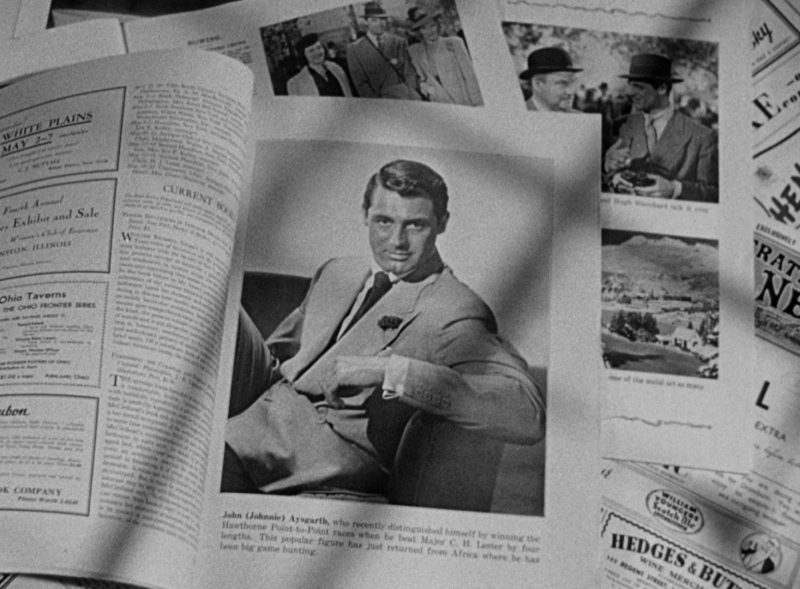

What I like about this is that we see it very early on, before the events in the photos at the top even happen. Has Johnnie invented time travel? Probably!

It’s not damning Suspicion with faint praise to say that even a lesser Hitchcock is going to be better than most other films. His films always look and feel different than any others of the era; they have texture, interest, a presence other films can try for but never quite achieve. Suspicion may not be the best Alfred Hitchcock had to offer, but it was still one of the best films to come out of the early 1940s, and influential enough that it should be on everyone’s must-watch list.

Suspicion is now available on MOD Blu-ray from Warner Bros. in a very nice print with especially fine sound.