This is the official SBBN entry for The Mary Astor Blogathon, hosted by Tales of the Easily Distracted and Silver Screenings. Check out all the entries here!

This is the official SBBN entry for The Mary Astor Blogathon, hosted by Tales of the Easily Distracted and Silver Screenings. Check out all the entries here!

***

Holiday began life in 1929 as a successful Broadway production. Written by Philip Barry, whose work tended to focus on the upper classes and their isolation from the real, modern world, the play was originally written under the title The Dollar. It was Barry’s second big stage hit, his first being just two years earlier, and helped cement Barry’s reputation in New York. When Barry was featured on the cover of Time Magazine in 1932, the accompanying article noted that a new Barry play was a social event, one that would clog streets around theaters from hours thanks to the excess traffic and crowds of fans waiting to catch glimpses of their favorite stars and politicians in the audience. His plays were often comedies of manners, positing that wealth could not provide the true necessities of life, and featured female leads who eschewed their riches, instead looking for a deeper meaning to the world; Holiday and The Philadelphia Story (written a decade later) both follow this formula and are his most famous plays.

Hope Williams played older sister Linda in Holiday on Broadway, and Katharine Hepburn was her understudy. Hepburn would go on to play Linda in the better-known 1938 film version of the play, as well as the lead in both the play and film versions of Philadelphia Story. Hepburn and Barry had careers which intersected frequently in the early 1930s. By 1938, Hepburn was infamously labeled as “box office poison” while Barry also suffered from a hit to his reputation after he lost an infant daughter earlier in the decade; he was writing more macabre plays which did not sell. Hepburn bought out her RKO contract in 1938, and as a freelancer took to Columbia to do the remake of Holiday, though the film was only a moderate success and was not the comeback the star hoped for. She left for the stage, bought the rights to The Philadelphia Story, and finally achieved her comeback.

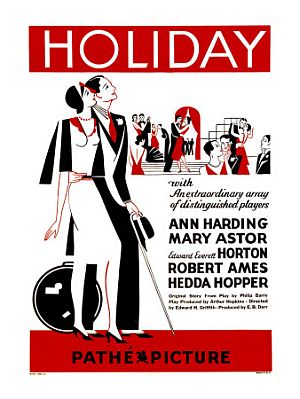

The first film version of Holiday was not the more famous 1938 version, but one from 1930, starring Ann Harding as Linda, Mary Astor as Julia, Robert Ames as Julia’s fiance Johnny Case, and Monroe Owsley as Julia’s and Linda’s brother Ned. Owsley was the only actor from the original Broadway play to return for the film. (Tangentially, Donald Ogden Stewart, who had played Nick in the original Broadway production of Holiday, wrote the screen adaptation of Philadelphia Story a decade later.)

The 1930 film is a close adaptation of the play, though so much had changed in the two years since it premiered that some modification were in order. For instance, Johnny is given the opportunity to take an early retirement, his plan being that he will work later in life after finding himself. This opportunity comes in the form of a savvy stock trade, and indeed, when the play opened on Broadway in November, 1928, it was still feasible for a man like Johnny to have made $20,000 in one good investment. By the time the film opened in July, 1930, it was impossible to believe such a thing, and for a film to rely so much on stocks without mentioning that little thing known as Black Tuesday is an enormous misstep, still obvious over 80 years later.

Regardless, Johnny’s plan is somewhat of a secret to his love Julia. When Holiday opens, Julia (Mary Astor) and Johnny have just arrived at her palatial estate. They’re happy, laughing and obviously in love, but Johnny (Robert Ames) had no idea she came from a rich family. He’s overwhelmed with the idea of being a poor kid who just barely ekes out a living trying to ask the famous businessman Edward Seton (William Holden, the first one, not the Picnic and Network one) for his daughter’s hand in marriage. Julia’s older sister Linda (Ann Harding), though, immediately takes a liking to him, pronouncing him as someone who has just brought life into the house, especially once he tells Linda about his early retirement. She promptly starts planning how to pull one over on their father so he will agree to let Julia and Johnny marry.

I make a lot of jokes on SBBN about classic Hollywood actors being bland, though I realize that was, at least in part, an intentional style. Men need only be cool, collected, unemotional, and look nice in a tux or, in the case of Westerns, in tight cowboy duds. The more standout, emotive parts went to women who, historically, had been the bigger Hollywood stars, while the actors were often supporting the solid female roles. That said, Robert Ames is plain old bland, so much so that the idea that he has somehow breathed life into a stuff rich family is impossible to believe. He doesn’t seem free spirited at all, but rather someone who should be a dull vice president of a bank.

Ann Harding is the unquestionable star of the film, and she has a lot of charm and most of the humorous lines — the ones that don’t go to her sullen brother Ned, at any rate — but this film is hard to find and all available prints are so poor that you can’t always hear her properly. I can’t blame it entirely on the print, however, as both Mary Astor and Edward Everett Horton speak quickly but are easily understood despite the sound issues. Much of the problem with Harding is her phrasing, which is incredibly poor. Monroe Owsley as her brother suffers from this problem too. He has the look down pat, so much so that he reminds you of someone like a young Richard E. Grant or Hugh Laurie in one of those modern films set in the 1920s. His delivery is unfortunate, however, as he includes lengthy pauses in sentences at moments which aren’t natural to conversation. Ann at least uses natural phrasing, though exaggerates it. When talking to Johnny about his problems with Julia, for example, Ann delivers the line, “She’s worth… a try… Johnny,” with a full breath at each pause. Her insistence on using a quavery, high-tone voice that becomes more shrill with more emotion means that when she gets upset, she is unintelligible.

Linda does get upset, and often. She is so impressed with Johnny and so heartbroken that her beloved sister Julia will be leaving the house that she insists on having a small, intimate engagement party, one with very few guests. She will plan this herself, and they all toast to the idea.

But one quick jump cut later and we see the party has become one of those 300-people affairs held in a large ballroom with a sturdy floor to support all the heavy gowns, jewels and stuffed shirts. Linda is beside herself, so holes up in her old playroom upstairs with a few friends.

Her reaction is exceptional, more so than it was made to appear in the 1938 Holiday. Hepburn very wisely realized that the dialogue in Ann Harding’s hands became overwrought and outdated, and though her delivery (and even some blocking) in the 1938 remake matches Harding’s more than it properly should, she adds a wry wit — what we would probably call snark nowadays — and never takes herself too seriously. The playroom party is part of that wacky, screwball feel to Linda’s character. In the original film it’s pure, unadulterated regression, the act of a woman who has never had to deal with anything serious in her life and so throws a tantrum when things don’t go her way. She is also revisiting her past, not only wishing things were as they had been as a child, but wondering how her life became so empty and wrapped up in the trappings of wealth.

Her musings are meant to be tempered by the antics of the hipster couple Nick and Susan Potter, played by Edward Everett Horton and Hedda Hopper. Horton would go on to reprise the role, somewhat rewritten, in the 1938 remake. The two tell jokes in that peculiar late-1920s manner, where the joke is really just a wacky story that doesn’t make much sense. The film hits the humor and wit a little hard by having Linda or Johnny stifle laughs when no real joke was made, or showing some unpaid extra, a maid or a party guest usually, chuckling at the end of the scene to reassure the audience that it was indeed funny. Despite the weak comedy, Eddie Horton is terrific, of course, because the man never gave a bad performance in his life. Hedda is a self-conscious bore, and it’s difficult not to spend the entire scene distracted by Hedda’s antics. She will look like she is just about to wander around when she remembers that the cameras are rolling, then remembers her blocking, and in the middle of someone else’s sentence will suddenly step into place, dip her leg, put her drink in the correct hand and then start listening to the person talking again. It’s bad. It’s MST3K bad.

Nick and Susan are both meant to be examples of the idle rich, and Linda and Julia are both afraid, in different ways, that Johnny Case will become idle himself. Yet the hipster couple are clearly Linda’s best friends, beloved and admired, the kind of people you want at every party. Linda probably, though we are never told, wouldn’t mind if Johnny became idle while “finding himself.” She loathes a business-oriented rich couple that show up every so often, implying that idleness a la Nick and Susan is acceptable to her while becoming a stodgy businessman is not; that said, she makes it clear she doesn’t believe Johnny’s plan is true idleness. It’s probably inconsistent, or would be if her true feelings beyond a sort of mild rebellion against her own wealth were ever revealed.

Julia is never warm to either the business couple or Nick and Susan. Without any real allegiances shown, we’re left to assume that what Julia says is the way she feels. She primarily worries that her husband-to-be will become idle off her money and it will appear that he only married her for her wealth, and truth be told, his weak promise to keep their money separate fails to convince. She doesn’t seem materialistic or insensible most of the time, though it’s obvious that she is meant to be seen as bad, perhaps even evil.

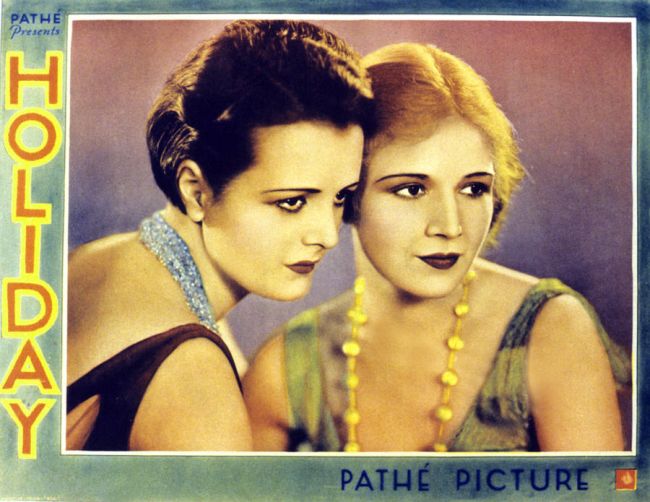

The sisters have a much more pronounced, intense relationship in this first film version of Holiday, and Mary Astor, the star of our blogathon, is miles and away better than Doris Nolan was in the 1938 film. The character is reduced somewhat in the remake, probably to make it easier to believe that Cary Grant (Johnny) was never that serious about Doris Nolan (Julia) in the first place. But Johnny is more than serious about Julia in the 1930 version, and up until about five minutes before the end, they’re embracing and smiling and happy together.

Astor unquestionably gives the best performance in this film. She is modern, strong and capable, and the reason she possesses while discussing Johnny’s slightly wacky plan completely undermines the claim that being rich is inherently immoral. It’s questionable whether Barry intended such a black-and-white reading of the situation, anyway, as he wrote Julia as frequently protesting against her father pushing for more business than pleasure; her problem is that she does not protest enough. Further, she and Johnny do agree that he will work for two years and then, if he still wants, take his early retirement. While Harding and Owsley both hammer home the idea that Johnny will be ruined if he’s allowed to become rich through marrying into a high-level job and wealth, Astor lends the situation some much-needed ambiguity, and her performance alone elevates this early talkie above the stodgy stage play almost everyone else in the cast apparently wanted it to be.

In 1930, Mary Astor was at a crossroads in her career. After silents fell out of fashion, she was told her voice was not acceptable for talking pictures and had trouble finding work. She took diction lessons and even trained as a singer, but her voice was deemed too low, even after appearing in the welcome-to-talkies extravaganza The Show of Shows (1929), and she was still relegated to silents as late as 1929. It was only through the efforts of friend Florence Eldridge, stage and screen actress, that Astor was able to secure a stage role that proved her voice was far from unacceptable. Her first real talkie was Runaway Bride (1930, remade in 1999).

Also in 1930 were the films Ladies Love Brutes and, of course, Holiday, though both were somewhat stressful events for Mary. According to author Anthony Slide, Mary Astor hated everything about Ann Harding, her acting, her PR, even her manner. It’s interesting to compare Astor’s solid, unadorned performances of this era with the role she’s most famous for, as Brigid in The Maltese Falcon. Brigid is a high-strung liar, all hand-wringing and drama with a false-high, shaky voice, and Brigid bears more than a passing resemblance to Ann Harding here in Holiday.

Astor reportedly shrugged Harding off as “a piece of shit” during filming and vowed never to work with her again. Mary was well known for her salty language, though more than one story about how she was treated makes her seem less volatile actress and more like someone simply willing to stand up for herself. She once told of a time when publicist Herb Sterne demonstrated, without her permission, that her wavy hair could be tamed for the role of a Spaniard in Don Q., Son of Zorro (1925) by smearing butter into it. Later versions of the story focused on her outburst, though I think most people would let fly with a little justifiable rage if some guy jammed butter onto their heads.

Astor in Holiday gives an almost revelatory performance. Her warm smile early on very subtly becomes a polite, photo-ready society smile by the end of the film. Her voice deepens almost imperceptibly, and her body language changes from fluid to stiff and guarded. This is all undermined a bit by the stagey tricks used, like changing her hair and clothes so noticeably. When she first arrives back at the estate with Johnny in the opening scene, she is in a plain traveling suit and sensible shoes, and eventually graduates to dark, vampy, backless gowns. Linda also undergoes a change, though from a lovely knit ensemble to a dark gown with a modern neckline but overly-modest skirt, and later a hilarious lacy affair meant to make her appear angelic but instead making her look like someone’s grandmother going to a wedding.

The notion that Linda is the “good girl” is made all too clear when she confronts Julia while wearing her 27 layers of lace. Julia dares to walk around her own bedroom in her lacy underthings, powdering her skin and standing up for what she believes in. Harlot!

Holiday was a hit. Astor had proven her voice was in fine form, and her performances in Holiday and Ladies Love Brutes changed studio’s minds about her viability. She was offered a contract with RKO, which she ultimately turned down. Her husband had died in a plane crash in early 1930, and about the time Holiday was released in the middle of the year, she suffered a nervous breakdown. A year later in 1931, she married the doctor who treated her during her illness. The marriage infamously imploded a few years later and she was embroiled in scandal when her husband filed for divorce, repeatedly referring to an infamous diary where she detailed some of her extramarital affairs. This scandal fortunately did not hurt her career, and according to some, it actually helped it.

Holiday has a mixed modern-day reputation. A lot of people find it better, or at least equal, to the more famous 1938 version. It is unquestionably dated, however, more so than the remake even though the two films are only eight years apart and both embrace the skeevy idea that sisters are essentially interchangeable — if romance with one sister doesn’t work out, just try the next one.

The 1930 version uses many of the same techniques as silents, including having characters walk in and stand there for a few seconds, framed by the camera as an obvious introduction; all that’s missing is the little title card:

—Miss Ann Harding

The staging is stiff with boring blocking, as you can see in the toast above, where the two women are sitting while the two men stand, each on the proper metaphorical side for that particular scene. The cast is wildly uneven, though many films in the very early 1930s suffered from the same issue. Astor’s performance reminds me of Bette Davis’ in Cabin in the Cotton (1932), where the lead Richard Barthlemess was clearly still acting for the silent screen, while Bette flies through the film like a whirlwind, dragging Cabin, protesting, into the modern day. Holiday feels very similar, though is pulled in more directions than the usual confused early talkie. Owsley is sometimes still playing to the back of the theatre, Harding hasn’t yet transitioned her style to talking pictures, while Ames is probably just trying to hold his personal life together enough that he can say his lines without stumbling. Meanwhile Eddie Horton and Mary Astor are already in 1933, embracing the future of film and giving honest, realistic portrayals of complicated characters.

***

SOURCES:

The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Expanded and Updated by David Thomson

Screen World Presents the Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors, Volume 1, edited by Barry Monush

Screen Savers II: My Grab Bag of Classic Movies by John DiLeo

Katharine Hepburn: A Remarkable Woman by Anne Edwards

Leonard Maltin’s Classic Movie Guide by Leonard Maltin

Silent Players: A Biographical and Autobiographical Study of 100 Silent Films by Anthony Slide

“The Theatre: Angel Like Lindberg” in Time Magazine, 1932

Wow – terrific analysis of this movie, and it sounds like Mary Astor is fabulous here. Edward Horton is a fave of mine, too, and he never did give a bad performance, did he?

Some of your descriptions made me laugh out loud, and they’ve prompted me to put this on my must-watch list.

Thanks for participating in our blogathon! :)

Thanks for hosting the ‘thon!

Mary really turns Holiday into a movie worth seeing. It’s on YouTube but as far as I know was never released on VHS or DVD, so it’s either YouTube or a “collector’s copy” unfortunately.

Wow!! I really need to add this film to my “must see” list of films..

I’d really like to see the 1930 version so I can compare it to the later version. Astor would have made the 1938 version a lot more interesting, I’m sure. Nice review.

Another entry that made me know that I’ll have to watch this! So nice to know hay Kate’s and Barry’s lives connected during the 1930s. Thanks for the great article.

Don’t forget to read my contribution to the blogathon! :)

Kisses!

Thanks Le — I saw your article and LOVE the pictures of Mary you got for it! Great stuff!

Stacia, BRAVA on your thorough, fascinating post about the 1930 version of HOLIDAY and your discussion of our gal Mary Astor’s life and times, including the tragic plane crash that cost the life of her fiance. You really delved into Mary’s dedication to her craft as an actress, as well as being strong enough to stand her ground when people tried to take advantage of her. Even though the HOLIDAY print could have been better, it’s clear that Mary Astor had star quality and screen presence. Thanks a million for your superb contribution to our Mary Astor Blogathon!

Thanks Dor! And thanks for hosting the ‘thon!

Very nice write-up, though I do disagree with you on a couple of points. As I said in the other entry about this film, while Harding doesn’t compare to Hepburn’s performance – one of my all-time favorites of Hepburn’s – I actually think it’s pretty good. She does successfully convince you she’s out of step with the her father and the “all-business” credo of the family. And while I agree with you Astor (and Edward Everett Horton) are terrific here, I do find Astor’s transition from in love with Johnny to being a cold, snobbish character very abrupt, though I blame the writing (whatever you think of Doris Nolan in the 1938 version, Julia at least is written better here). I do agree, of course, about Ames’ performance as Johnny, Owsley as Ned, and especially Hedda Hopper as Linda.

I think the entire film changes abruptly immediately after the scene where they all toast to the idea of Linda giving a small, intimate party. It cuts directly to a large ball and from that moment on Ned is angrier, Julia is colder, and Linda is more high strung. It’s like there’s a scene missing, it’s so noticeable.

Thanks so much for the great review and the fun anecdotes. The more I learn about Mary Astor, the more I like her. And if someone ever put butter in my hair… BAM! I’m amazed she didn’t kill him.

I know! That guy would have been wearing the butter knife in his hair and eating the butter dish if he’d tried it on me!

I love Astor, she sounds like she was a terrific lady to be around.

Thanks to Mary Astor, I know how often George S. Kaufman could ejaculate in a single evening, but you know what? I forgive her, because she was such a smart actress — one of the precious few who seemed to realize that there was, you know, a camera in the room.

Thanks for another illuminating review, Stacia. I’ve seen the 1938 Holiday, but never knew an earlier version existed. By the way, how did they deal with consumption of alcohol? I know a lot of pre-Codes just took the existence of bootlegging for granted, but I’m always curious about the ways filmmakers acknowledged, ignored, or finessed the question of drinking during Prohibition.

I seem to recall they make a sly comment about their bootlegger at some point, but they have an absolute ton of champagne at the party so it’s obviously a Hollywood-style bootlegger — just mention him briefly and you can excuse all the alcohol in the world.

Hi, Stacia!

Loved your review of the original Holiday. There is a lot to love about it and I particularly enjoyed Astor and Harding on screen together. Two gals I would love to spend a weekend gossiping and having a cocktail with. : )

It was great to read your comparisons to the original then the remake. What worked for both, and the changes made. I adore Cary so I did enjoy the 2nd go at it but the original holds up very well. At least the remake was a success and not a total stink bomb like the remake of The Women. ha ha

A fine contribution to the Blogathon.

Have a great weekend!

Page

Hi Page, and thanks! I do think the remake is better liked because no one can hold a candle to Cary Grant, certainly not Robert Ames, With him the whole plan of retiring when young and working later when he’s old makes sense. Sometimes with Ames I got the impression he kept thinking, “Why doesn’t Johnny just take the banking job? That’s what I would’ve done!”

After years of hearing about this film, it is your post that has finally made me move it to my “must find” list. I have always loved the 1938 version, but I can see how it would work with Astor as well. Thanks so much.

Thank you for excellent review. May try and watch it on YouTube. I didn’t know Edward Everett Horton had played in this version too.

Vienna’s Classic Hollywood

Pingback: Academy Monday – Watch: Holiday (1930) – Edward H. Griffith | Seminal Cinema Outfit