“In any case, this film isn’t a Western. It’s really about people who want nothing more than a home of their own. That was actually the great American dream at the time, and in all the statistical questionnaires that ask what Americans aim for, 90% always gave the answer: ‘Owning a home of my own.’ And that’s what the film’s about.” – Nicholas Ray

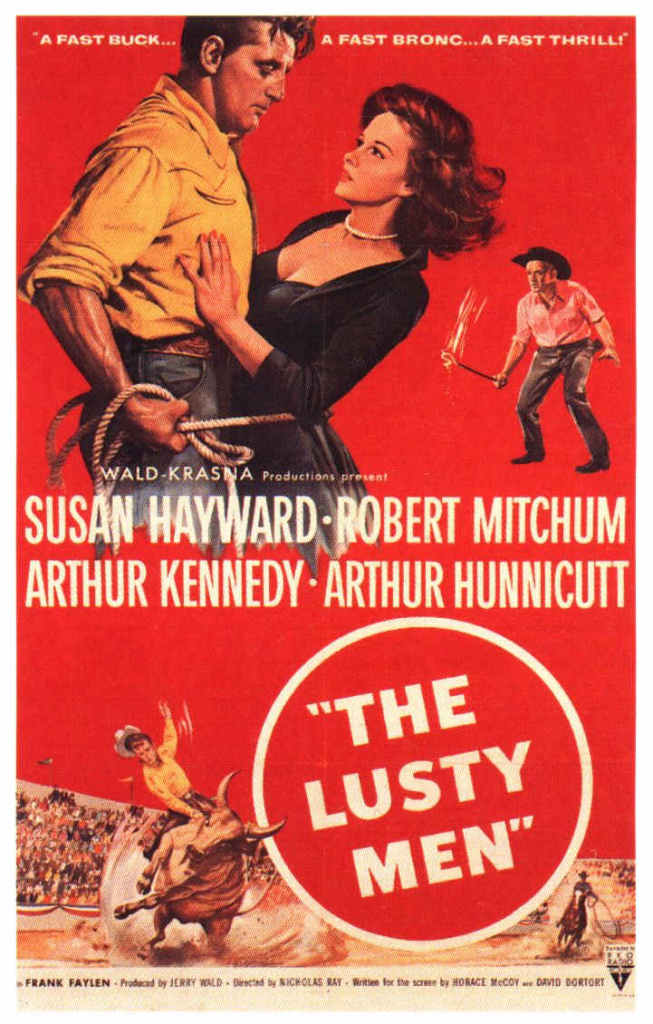

Jeff McCloud (Robert Mitchum) is an aging champion rodeo rider who, after one too many falls from an angry horse, finds himself limping back to his dilapidated childhood home. After sharing some pat cowboy wisdom with the current owner, Jeremiah Watrus (Burt Watrus), he meets Louise and Wes Merritt (Susan Hayward and Arthur Kennedy, respectively), there to take another look at the home. They’re ranchers, saving up for a place of their own, and have had their eye on the Watrus place for some time. Wes harbors some bronc ridin’ dreams of his own, and soon he not only wants Jeff’s childhood home, but Jeff’s friendship, mentorship, and former career. Meanwhile, Jeff is pretty sure he wants Wes’ wife.

It may seem like a standard melodramatic love triangle, but beyond their attractions, desires, comforts and dreams, there’s one other thing that links these three people together: they’re children of the Depression, all still with one foot in the past, the memories of growing up poor and rootless families in a disjointed America always playing in their minds, even when they don’t say anything — and other than Louise, no one ever really does. But Jeff’s quiet gaze at his old childhood home, a shack that looks like it barely made it through the Dust Bowl, so neglected that the toys and comics he stashed under the house decades earlier are still there, speaks volumes.

Wes, a few white lies and minor temper tantrums later, goes on the rodeo circuit, and Louise is forced to follow. For Louise, with her memories of childhood and a rough coming-of-age in a hash house, the rodeo circuit must be sheer hell. Visually, it has the dreary presence of a sideshow, with the small trailers and seedy hangers-on, a world where a rodeo rider with a working shower in her trailer is an anomaly. The scene is even less glamorous than the pre-Codes the visuals harken back to; there are no glittery costumes as in Freaks (1932), none of perverse and gauzy sentiment of The Unknown (1927), no saucy fun a la Hoop-La (1933). These rodeo shantytowns are the true descendants of the Depression, dusty, low-rent outfits where the periphery of society hope to catch their dreams.

But it’s not Louise’s dream. Like so many pre-Code Barbara Stanwyck characters before her, Louise was a beautiful girl who held out for a respectable man until she found Wes, happy to work the land and slowly but steadily earn enough to make a home. They were compatible, hard working and responsible, but Wes could never shake what seems an almost childish dream of making a living bustin’ broncs and ropin’ cattle. Had serendipity not brought Wes and Louise out to Jeff’s old home to once again look at the ranch they hoped to buy, Wes might never have taken that final step toward becoming a rodeo rider. If Wes believes, at least at first, that the money he makes at the rodeo is an investment in their future, Louise believed Wes to be her investment. When Wes and Jeff, whom she blames for Wes’ crazy dreams, force her hand and drag her out to a series of rodeos, where she’s in danger from a host of leering and violent men, her assessment is both hilarious and spot on: “Men. I’d like to fry ’em all in deep fat.”

Praised by Cahiers du cinéma, especially Jacques Rivette, The Lusty Men was considered, if not the very first, at least the first important postwar Western. Rivette’s praise, however, seems strained at times:

“Everything always proceeds from the simple situation where two or three people encounter some elementary and fundamental concepts of life. And the real struggle takes place in only one of them, against the interior demon of violence, or of a more secret sin, which seems linked to a man and his solitude. It may happen sometimes that a woman saves him; it even seems that she alone can have the power to do so; we are a long way from misogyny.”

Though this comes from Rivette’s review of Lusty Men, it’s strangely a far more accurate assessment about Ray’s yet-to-be-made Johnny Guitar (1954) than Lusty Men. The more fully formed characters of Johnny Guitar are absent in Lusty Men, to an extent, so much so that Jeff’s macho man nature is, even for 1952, abusive to Louise, something many critics then and now attempt to shrug off with the notion that it was okay because Susan Hayward was a woman who could handle herself.

And of course, we can’t forget that the women in this scenario are shown as attempting to thwart the freedom of men, a heinous crime given a man’s freedom so unabashedly represents sexuality, potency, virility. Unlike the antics of Western directors like John Ford and Howard Hawks, who were so taken with the idea of male personal freedom equaling erection that many a rock, cactus and fencepost lingered in the background as phallic stand-ins, Ray makes his characters’ quest for power far more personal and internal, as philosophical as it is physical.

It may be a little difficult to swallow Mitchum as the older, washed-up bronco buster to bright-eyed newbie Arthur Kennedy, when Mitchum was actually three years younger than Kennedy and in peak physical condition. Hayward seems a bit too East-Coast-hardened to wind up on an isolated ranch in the Western United States, and there are many moments where you wonder why she doesn’t just pack up and go back to New York to get away from these deep-fried misogynists who don’t appreciate her nearly as much as they should. Ray’s visuals are a touch ham-handed at times, American flags and cowboy hats and stock rodeo footage holding up a little too much of the plot.

Yet The Lusty Men is a an important moment in the American Western, and a key transitional work in Nick Ray’s oeuvre, the director borrowing much of his well-honed noir aesthetic for the Western genre, but in a way no one else in U.S. cinema was doing at the time. Rather than merely relocate standard noir tropes and characters to the dusty West, Ray understood that rural America shared many of the same basic existential issues of the urban crime world, but with their own, slightly different sets of challenges, goals, desires and needs. The Lusty Men is a truly remarkable document, a particularly melancholy and bleak look at the American Dream.

The Lusty Men is now available at Warner Archive. The first run of these DVDs are traditionally pressed, not made-on-demand, in anticipation of high demand.

Great insight about its relationship to the precodes. Never thought of that. Isn’t this the one with “No horse that can’t be rode/ No man that can’t be throwed”? Wise words, really! A precursor of “Sometimes you eat the b’ar, sometimes the b’ar eats you” from THE BIG LEBOWSKI. Okay, that’s all I’ve got, goodbye.

That’s the one! Easy to mix the phrase up into, “no man that can’t be rode,” for the inevitable R-rated remake of LUSTY MEN.