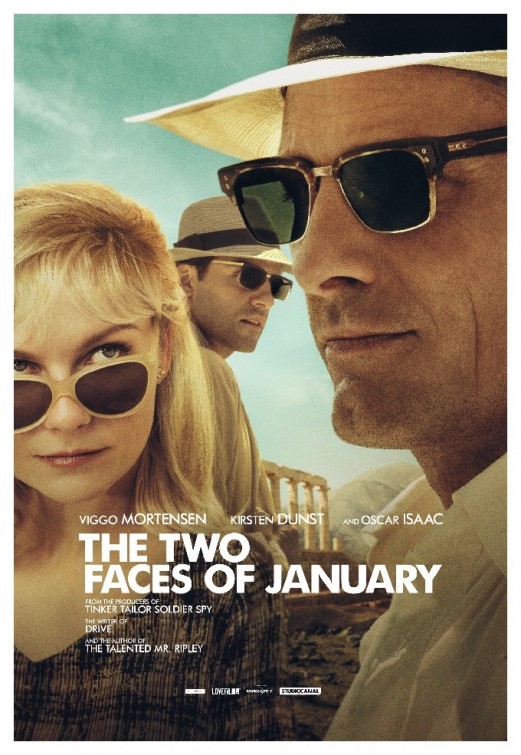

The Two Faces of January

★★★½ / ★★★★★

Director: Hossein Amini

Magnolia Pictures (Official Site)

96 Minutes

In Theaters September 26, 2014 (Limited)

–

Rydal (Oscar Isaac) is a young American ex-pat in Greece, a part-time tour guide and full-time grifter who finds himself intrigued by a couple vacationing on the island. Chester MacFarland (Viggo Mortensen) notices Rydal’s stares, and his plucky young wife Colette (Kirsten Dunst) makes an introduction; soon, the trio are holidaying together, Chester impressed with Rydal’s ingenuity while Rydal, somewhat despite himself, sees Chester as a father figure. Signs of intergenerational conflict and Rydel’s rather indulgent Oedipal complex show almost immediately, but there is no polite sidestepping of these issues for the trio: Chester finds himself in deep trouble and Rydel is enlisted to help, propelled by vague notions of heroism and profit. Soon, Rydel is in as much trouble as Chester is, and they are all on the lam.

The Two Faces of January is a languid, mature thriller that boasts a gorgeous retro feel. There are plenty of nods to Agatha Christie and Tom Clancy here, elements of Alfred Hitchcock and Carol Reed as well, all tied together with impeccable framing and a classic 1960s British look — think Ted Moore or Geoffrey Unsworth — courtesy cinematographer Marcel Zyskind. Just as in any good thriller, as the plot unfolds, so too do the characters, our ostensible hero revealing himself to be self-absorbed and emotionally stunted, our alleged villain with a maturity and understanding that belies his con artist nature.

Chester and Rydel butt heads from the beginning, their perverse father-son relationship providing the basis of the title: January is named after the two-faced god Janus of ancient Rome, who looked both toward the people and the gods at the same time, and who represented transitions and new beginnings. But as noted by Peter Goodrich in his Oedipus Lex, Janus was also a common metaphor within discussions of women’s rights in the Victorian era, especially on the topics of suffrage and sexual liberation. Janus represented both the good to be gained by allowing women the same right as men, but also the allegedly bad, or at least complicated, issues which arose when women were allowed the same free will men enjoyed.

In film noir, a close cousin to the cinematic thriller, this two-faced metaphor fits particularly well into the trope of the duplicitous woman, the femme fatale feigning sexual desire to distract, to manipulate or to deceive — think Brigid O’Shaughnessy or Kitty Collins. But Colette, despite what the men in her life may believe, is no femme fatale, she’s just a woman married to an older man who is in trouble, either with the law or some shady creditors or both.

Yet as Rydal and Chester vie for Colette, it becomes obvious they wish to own her rather than love her. She knows she’s a pawn, but never grasps the full implication of this, not even when Chester accuses her of duplicity, or when the men constantly question her claims, even the unimportant ones. Colette’s personal identity is appropriated by both men for their own needs, and Colette doesn’t know enough to realize that neither man has much regard for her.

Sadly, the film doesn’t have much regard for Colette, either. Written by Hossein Amini, who also directs — this is his first feature film — The Two Faces of January prefers to focus on Rydel’s father fixation, and in framing the men as two metaphorical sides of the same god’s face. In doing so, Kirsten Dunst becomes as much of a pawn as poor Colette is. To be fair, some of this may be due to Dunst only skimming the surface of the character, eschewing the chance to imbue Colette with depth. Mortensen does much of the heavy lifting throughout the film in terms of acting, though is unfortunately sold out by a finale that doesn’t do justice to the intricate character he created. Yet the end of Chester’s character arc, as unsatisfying as it is, has nothing on Colette’s story, which ends in a frankly offensive and cheap manner.

That said, there are some fine moments in The Two Faces of January, largely deriving from the filmmakers being content to create an old-school thriller free of gimmicks or strained attempts at modernization. The plot moves at a fine pace and features the requisite twists and turns, buffered by a restraint that heightens tension. With mostly solid performances, especially from Mortensen — and, it should be noted, Daisy Bevan in a small but pivotal role — The Two Faces of January is a worthwhile thriller in the classic mold.

This is a splendid review, and overall, I couldn’t agree more. I love the film’s overall elegance, pacing and as you say “restraint.” But I did want to defend Dunst’s performance a bit…I thought she brought quite a bit of empathy to this adventurous, naive young woman who married for glamour and excitement, and got more than she’d bargained for. Maybe it’s because I haven’t seen Dunst in a while, but I love the sort of drunk-exhaustion that begins to take over her body as she’s dragged deeper and deeper into a game she didn’t design. At times, she’s a resigned “good sport”, doing her best to play through, at others, a betrayed wife understandably tempted by a man who seems younger, kinder, and stronger …I agree that the film doesn’t have as much regard for her as it could/should, but when Colette’s storyline fades out, I felt the film really lost some of its humanity and electricity.

Thanks, RP! I agree that she’s quite good in the scene in what looks like a walkway after they’ve trudged all the way back to civilization, and also that when her storyline ends, the film really suffers. Her physical presence was terrific in the film, but I just couldn’t shake the feeling that Dunst wasn’t emotionally there.