Black Patch is a dark and serious film, which is why it has an adorable little line drawing of the marshal and his badge on the poster.

Black Patch is a dark and serious film, which is why it has an adorable little line drawing of the marshal and his badge on the poster.

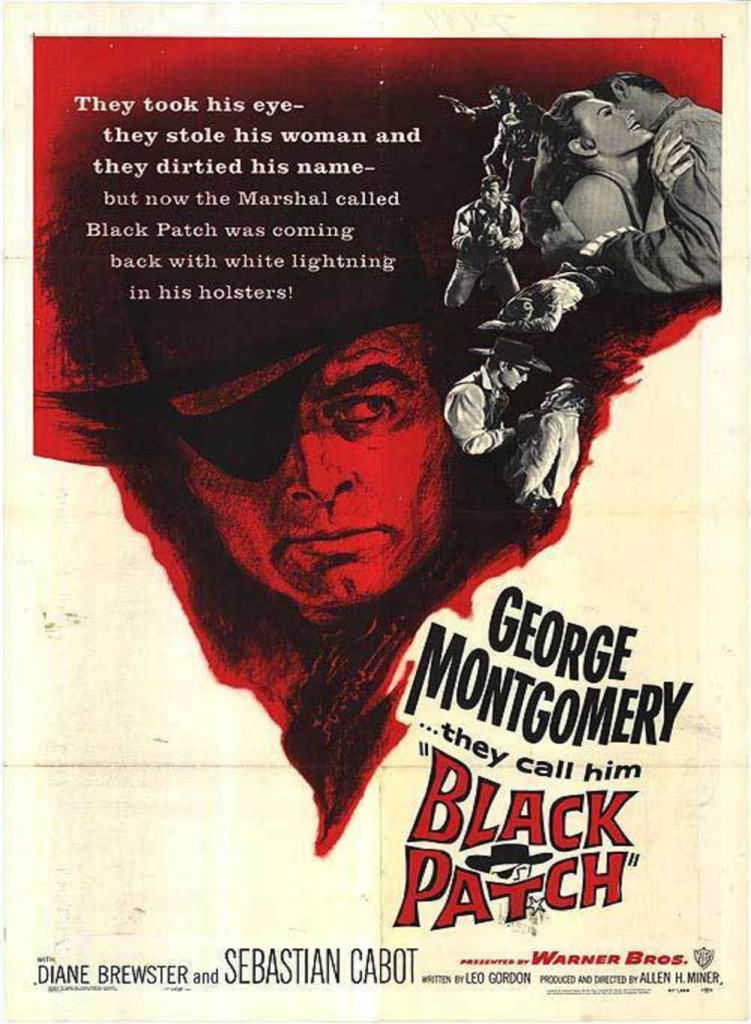

Directed by Allen H. Miner, known primarily for his television work, Black Patch (1957) is a strange and wonderful little Western, a true independent film that took the kind of risks one rarely sees in this particular genre. Conceived by Leo Gordon, a hard-working character actor who also appears in the film as co-star Hank Danner, it seems the development of the script happened almost by accident. Gordon had never sold a script before when he casually mentioned he had an idea for a TV show:

“When Charles Marquis Warren was directing the pilot for “Gunsmoke,” I told him I had an idea for an episode. ‘Don’t tell me, write it,’ he answered. I went home and the next thing I knew I had 110 pages. I showed it to my agent. Next thing I know, George Montgomery wanted to buy it. That was ‘Black Patch’. Gene Corman negotiated the deal. That’s how I came into contact with him and Roger Corman.” – Leo Gordon (from here / quoted here in a fine review by Toby at 50 Westerns From The 50s)

Gordon would go on to write deliciously schlocky B-movie classics like Attack of the Giant Leeches and The Wasp Woman, which, in conjunction with his distinctly non-writerly demeanor, may account for the dismissive attitude many hold toward Black Patch. Leonard Maltin’s guide calls it “inconsequential trivia” and rates it with one of those cute little bombs — because calling something awful isn’t bad enough, one must be condescending about it, too — and Hal Erickson labels it “pretentious.”

Black Patch, however, is an astonishing film, confident enough to focus on characters other than the lead once in a while, and to remain quiet in moments other films would insist on stuffing with unnecessary dialogue. Tropes are played with, juggled around and turned upside down, the three-act structure is stretched to its very limits, and adult themes are introduced without any shoehorned-in modesty later in the film to reassure delicate audiences that naughty things never really happened. Black Patch fails at many of the usual genre expectations, but that’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

When it came to low-budget Westerns, George Montgomery was a goddamned rock star.

When it came to low-budget Westerns, George Montgomery was a goddamned rock star.

Stalwart Western leading man George Montgomery stars as Marshal Clay Morgan, a.k.a. Black Patch, a veteran of the U.S. Civil War, with the combat disorders and missing eye to prove it. He’s the law and order in Santa Rita, a small New Mexico town, and though not a tyrant, he is quite rude to Pedoline (Jorge Treviño), the pleasant goofball who cleans the jail, and 18-year-old Carl (Tom Pittman); their mere existence seems to irritate Clay. When Clay’s old friend Hank (Leo Gordon) arrives in town, the marshal learns that his former love Helen (Diane Brewster) married Hank when he never returned from the war.

This already-strained reunion turns deadly when Hank is pegged as a bank robber, and Clay is forced to lock him up. When Hank turns up dead that very night, the townsfolk are sure their own marshal shot him in the back, hoping to take both Hank’s money and his woman. Clay is ostracized, and not even Helen believes him when he insists he didn’t kill her husband.

Black Patch is occasionally heavy-handed, such as in this scene where a shot of Helen in the marital bed with Hank looks like a gussied-up prison.

Black Patch is occasionally heavy-handed, such as in this scene where a shot of Helen in the marital bed with Hank looks like a gussied-up prison.

Nearly catatonic and holed up in her hotel room, the beautiful widow is of particular interest to young Carl. When she gives Carl her husband’s gun and holster, she thinks nothing of it. Carl thinks the world of it, though, but it’s more than just symbolic manhood that he’s stumbled into. This skinny, pasty kid, dubbed by the townsfolk with the unkind nickname of “Flytrap” — likely because of his perpetually slackened jaw — plays with his gun for hours on end; meanwhile, the town gossips about the amount of time he’s spending with the Widow Danner in her hotel room.

All those quiet stares Carl leveled at Clay after Hank’s death coalesce into a simmering rage over the betrayal he feels the marshal has committed. Now, armed with Hank’s gun and holster, and possibly bedding Hank’s woman, Carl isn’t just out for revenge, but seems almost possessed by Hank’s ghost.

Black Patch features psychosexual themes and dark shadows, just as most 1950s Westerns did, but where any other film of the genre would be borrowing from films noir, Black Patch borrows from horror films. There are distinctly Val Lewton-esque sets, complete with unidentifiable shadows on the walls, and Jerry Goldsmith’s score is pure “Twilight Zone,” a good two years before “Twilight Zone” premiered on television. Something very gross but mostly unseen is going on with Clay’s wounded eye, possibly with his mind, and the seedy bar owner Frenchy (Sebastian Cabot) is one step away from being a villain in a Roger Corman Poe adaptation.

On top of all that, where subtext involving homoeroticism and lust were the mainstays of most Westerns of the era, in Black Patch, subtext is discarded with almost entirely. For instance, when Hank tells Clay that Helen never got over him, he says, “She waited. So did I.” We expect the requisite pause to process what we expect to be homoerotic subtext. Instead, immediately, and with a notable amount of force, Hank finishes the thought: “But with me it was different. I was waiting for her to get you out of her system.” Another example comes in the pointed mentions of Carl’s father and a self-appointed father figure, rendering any attempt to make Clay into Carl’s Freudian father figure pointless.

These lines of dialogue in such a spare script stand out as deliberate attempts to distance Black Patch from old noir-ish tropes, to create a new form of B Western. Further, you can see tiny moments in the film that seem inspired by the same films that also inspired the British New Wave. There’s a judgement-free embracing of flawed human beings, and the portrayal of intense, realistic, psychological traumas, none of which have pat answers.

It’s a difficult film, I think, in part because characters do things we don’t expect them to do. People steal money and we don’t know why. Some are engaging in perverse affairs, or maybe not, the film isn’t going to tell you either way. The town turns on Clay pretty quickly, but we don’t know how he was regarded before Hank’s shooting. The past hangs heavy in the air, and it’s not a neat, narratively convenient past, but a murky and complicated past that the film doesn’t feel matters much, anyway; the past is done and gone, and the entire tight 82 minutes of Black Patch is all aftermath.

Black Patch came and went without much of a splash in 1957, though received a good review in the New York Times. For years, it was almost impossible to find, though has shown up on TCM, greymarket DVDs and the occasional festival over the years. Thankfully, Warner Archive has just released this rare Western in a bare-bones MOD DVD, in a very nice print. The deep blacks of the film are preserved, and without any of the typical muddying of the visuals that you get so often on older films. The sound is good as well. This looks almost as nice as you would expect a well-known black and white film from 1957 to look, and is positively gorgeous for a film that was so unknown it might as well have been lost.

Great post. I particularly liked this: “It’s a difficult film, I think, in part because characters do things we don’t expect them to do.” That sums up the last half of the picture perfectly — but not just the characters but the filmmakers. We don’t expect them to leave so many things unexplained or to abandon the star of the picture for such a long stretch. It makes for a frustrating first watch, but the revisits get more and more rewarding. This one’s not easy, but it’s growing on me fast.

Hi Toby, thanks for dropping by!

I do think that the second half, when Clay fades into the background as Carl gains prominence, can be seen as amateurish, so I don’t really begrudge anyone who views it that way. But that whole change of focus starts during that double-action gun demonstration where they literally put Clay in the background as Carl shows his stuff, and that tells me that the filmmakers did it on purpose, not just because they were unable to construct a proper narrative.

Your review has sparked my interest in checking out this flick. BTW, Leonard Maltin (or one of his critic minions) has revised his opinion. In his Classic Movie Guide (Second Edition), BLACK PATCH gets a rating of 2 1/2 stars, and is described as an “interesting dark-tinged Western.”

Hey, thanks for the info. I never did buy the 2nd Edition but it looks like I should!

Actually, you might want to wait for the third edition of the Classic Movie Guide, which is due out in late September, this year.

Ah, thanks again. I thought the most recent was the last. I’m clearly not keeping up on breaking news around here!

Fans of Mystery Science Theater 3000>/i> will of course remember Tom Pittman as “Marv,” the painfully smart teenager who spends all his time doing intensely stupid things in High School Big Shot, which Frank Conniff in the MST3K Amazing Colossal Episode Guide pegged as easily, and by far, the most depressing film in the history of the show.

(And why is it that Kylie Jenner’s pneumatic kisser is enough to foist her on an unwilling public, but Tom Pittman’s lips, which covered equal or greater facial acreage, were not enough to vault him into the top ranks of juvenile stars?)

Fantastic review, one of those gripping reads that compels me to seek out a film I never even knew existed.