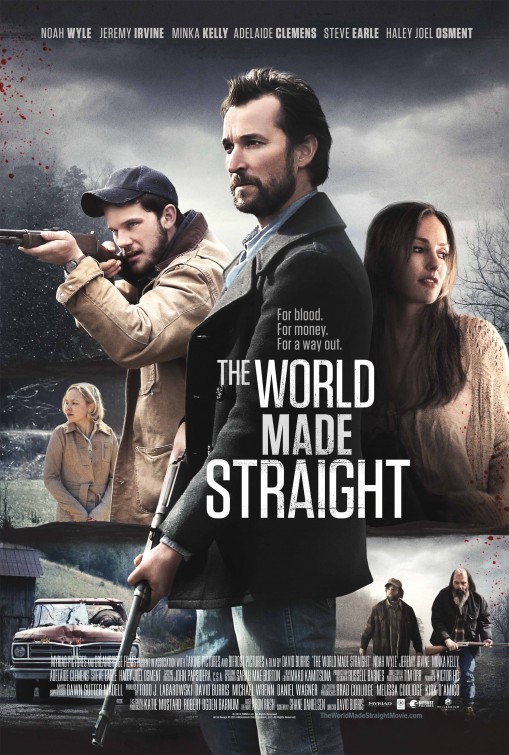

The World Made Straight

★★★ / ★★★★★

Director: David Burris

Millennium Entertainment (Official Site)

119 Minutes

In Theaters Beginning January 9, 2015 (Limited)

–

Teacher-turned-drug-dealer Leonard (Noah Wyle) takes a wary interest in restless high school dropout Travis Shelton (Jeremy Irvine) in David Burris’ neo-Gothic drama The World Made Straight. Travis has shown up at Leonard’s door with some stolen pot plants in the back of his pickup, hoping to score some funds after losing yet another job. It’s 1974, and the Appalachian hills of Madison County, North Carolina offer few prospects for the locals beyond chronic unemployment, booze and drugs or, for the lucky few, working at the hospital where most everyone gets stitched up after things go predictably wrong.

It’s a grim world of muted colors and cold drizzly days, a place where all of life’s answers can be found at the end of a gun. Cast out of his home by an abusive father and seriously wounded by Carlton (Steve Earle), a dangerous local drug dealer, Travis is begrudgingly taken in by Leonard, despite his sometimes-girlfriend’s protestations. The former teacher, known locally as “the Professor,” sees a curious soul in the boy. He may be cursed with a lack of education, hot temper and worthless friends, but Travis has a keen interest in learning, especially the history of the county and the Civil War-era tragedy which his own ancestors had been involved in.

The Shelton Laurel Massacre is no fictional construct but rather a very real event, a wholesale slaughter of civilians that garnered national attention during the Civil War. A group of Unionists who had raided Confederate salt stores were hunted down; shoot-outs ensued, killing nearly 20 of the looters in total. Not content with this result, Confederate generals tortured women and children in an effort to learn the whereabouts of the rest of the local men. When a small group of Madison County men were found, the Confederates killed them all, including 13-year-old David Shelton, who reportedly begged for his life before being executed.

Travis is greatly affected by the story of young David, whose death has been toned down in the film into something vague and sad and kind of noble in that vanilla way movies fall back on when they don’t want the audience to think too hard about the tragedy they’ve just witnessed. The thought of his young ancestor’s death seems to give the restless Travis a purpose — that purpose, of course, being revenge against the family what done his kin wrong, in time-honored hicksploitation tradition. It’s equal parts gimmick and hillbilly stereotype, an empty framing device and nothing more. It’s a hell of a thing to use a war crime involving the torture and slaughter of women and teens, just to add a little spice to an otherwise mild-mannered coming-of-age tale.

Travis first learns of the massacre not from his own family, but while browsing through old journals at the Professor’s home. How a feud so important it cast a shadow over the lives of not only his own family but the entire region in which he lives, and for over a century, could go completely unmentioned in Travis’ seventeen years on earth is a mystery. Equally mysterious is how Leonard in 1974 could be blasting a 1993 Connells song out of his tinny car speakers, and how a variety of faux Southern and Appalachian accents could pass for a unified local dialect.

Hidden amongst these head-scratchers and the occasional unfortunate line reading are the makings of what could have been a touching tale. Noah Wyle puts in a fine turn and does his best to make this self-conscious period piece into the movie it really wants to be, but is hindered by on-the-nose dialogue and a plot so railroad it must have been written in HO scale. Steve Earle exudes the exact right combination of cultivated charm and menace, and his voice is always welcome, no matter what the context.

The history of Madison County is expansive and deep, the people complicated and fascinating, but The World Made Straight can’t muster the strength to show them as they really are. It’s a film so frightened by complexity and ambiguity that it set out, quite purposely, to achieve inoffensiveness, and sadly succeeded.