This article on The Lodger (1944) is my entry for The Best Hitchcock Movies (That Hitchcock Never Made) Blogathon, hosted by Tales of the Easily Distracted and ClassicBecky’s Brain Food. Please visit the list of contributors here. The entries thus far have been absolutely stunning, and include ClassicBecky’s entry on the other major gaslight-based film of 1944, Gaslight. Check ’em out!

This article on The Lodger (1944) is my entry for The Best Hitchcock Movies (That Hitchcock Never Made) Blogathon, hosted by Tales of the Easily Distracted and ClassicBecky’s Brain Food. Please visit the list of contributors here. The entries thus far have been absolutely stunning, and include ClassicBecky’s entry on the other major gaslight-based film of 1944, Gaslight. Check ’em out!

This post contains spoilers for both the 1927 and 1944 versions of The Lodger.

***

Seventeen years may have passed between the two films, but Alfred Hitchcock’s 1927 silent The Lodger casts a deep shadow over the 1944 version. Despite being very late in the sound era, well past the days of early talkies, this 1944 version seems to have been self-consciously produced as a talkie remake of the silent flick. Heavy use of German expressionistic techniques so popular in the silent era are used throughout, several actors in the 1944 remake had already appeared in Hitchcock’s early films, and literally every actor has a beautiful speaking voice. Most noticeably, The Lodger plays heavily off the audience expectation that they knew who the murderer was based on the famous 1927 version.

It is 1888, and London is gripped with the news of Jack the Ripper, an unseen serial murderer who brutally kills women in the poverty-stricken area of Whitechapel. Just as the extra editions hit the streets screaming of another murder, a man named Slade appears on the steps of the Bonting home, in response to Mrs. Bonting’s advertisement of lodgings. Sad-eyed and overwhelmingly large, the soft-spoken Slade takes the second floor rooms and the attic above, claiming to need the space for experiments. Soon he begins to go out late at night. He is aloof and strange, shows a peculiar hatred of actresses, and even burns his medical case and blood-stained clothes, yet no one in the house is sure if their suspicions about his behavior are warranted.

This seems a silly thing when laid out on the table like that, but The Lodger’s greatest strength is in its ability to create doubt in the viewer’s mind. It would be too easy to paint the big fat antisocial guy as the murderer from the get-go, and make no mistake, lesser films have done just that. It would also have been easy to telegraph from the beginning that the film was either going to embrace the same ending of the 1927 original or do the exact opposite; instead, we get a portrait of a killer and those around him, the identity of the killer less important than the Victorian society the killer operates in. While Hitchcock’s 1927 The Lodger was about suspicion and mob justice, 1944’s The Lodger is about society’s inadvertent creation and nurturing of a sadomasochistic misogynist.

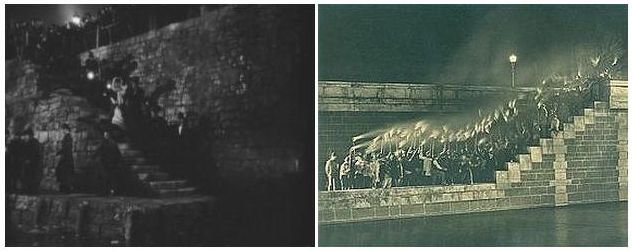

On the left, the final scene from The Lodger (1944); The Phantom of the Opera (1925) final scene on the right.

On the left, the final scene from The Lodger (1944); The Phantom of the Opera (1925) final scene on the right.

The Lodger is unquestionably pastiche, with hardly a single Victorian-Gothic horror cliche untouched within its overall aesthetic. Marie Belloc Lowndes’ novel, published in McLure’s Magazine in 1911, borrowed heavily from many Gothic horror classics such as The Phantom of the Opera and The Portrait of Dorian Gray, and this film version in turn borrows cinematic touches from the movie versions of those novels.

In its way, The Lodger was a groundbreaking film, or at least a precursor to the horror conventions we easily recognize nearly 70 years later. It was uncommon for an A-list film of the 1940s to repeatedly reference other films to the degree The Lodger does; some callbacks or references were usual, but an entire world built around conventions the audience would have been exceptionally familiar with was simply not done. The archetypical female horror characters of The Slut and The Innocent were also not fully realized in 1944, though most films in the genre featured a young, usually virginal and desirable woman tormented by the monstrous entity. Just as in The Phantom of the Opera, the singer, Kitty Langley, is ostensibly the innocent woman in this film; however, the audience sees actresses — euphemisms for prostitutes, more or less — in the same way Slade sees them, at least to a degree. It is no accident that the lovely Merle Oberon’s character is named Kitty, of course. And it is no lie that an actress caused the downfall of the lodger’s brother, though common sense dictates that his brother wouldn’t have “fallen” to venereal disease had he not slept around in the first place. Still, the double standard of sexual behavior of 1944 was well understood, and as innocent as Kitty is, she is also a can-can dancer fresh from Paris who shows off her panties to an audience filled with leering men in tuxedos.

We also recognize immediately the road Kitty has set upon. All the victims of the Ripper are former dancers, once beautiful starlets who danced on the stage, now Whitechapel hags living in squalor and doing things for money that polite society simply did not discuss. Both the victims are connected directly to Kitty, too, the first visiting Kitty on her opening night to relive her own successes in the same dressing room years before, the second seen in a bar performing a parody of Kitty’s “Parisian Trot,” the title of her hit dance act and, sadly, the only Hitchcockian dirty pun in the whole film.

Doris Lloyd as Jennie in The Lodger.

Doris Lloyd as Jennie in The Lodger.

Doris Lloyd puts in a terrific turn as Jennie, the second victim of the Ripper. Jennie has an extended sequence that appears directly after we feel a little pang of sympathy for the devil that is Slade. He has been napping in a chair in his darkened lodgings, Bible on his lap, alone and sad and emotionally cornered. Jennie is immediate contrast. She is vivacious, friendly and charitable. There is a wonderful bit of business in using a real publicity portrait of Doris Lloyd in the background, altered to look like something from Jennie’s long-gone dance hall days, and we see her beautiful past as she looks into the eyes of her foreshortened future, shaking in terror and unable to scream before the Ripper slices into her.

The entire film is packed with stellar character actors, all giving A-list performances in what must have begun as a high B-list flick. Sara Allgood as the landlady Ellen Bonting is the under-appreciated key to the film. The Lodger is certainly Laird Cregar’s film, but his pathetic awkwardness is highlighted by the almost surreal normalcy of the characters around him, and Ellen Bonting is the cornerstone of this solid Victorian middle class life. She is unflappable, formidable of face and figure, a conscientious woman with a most lovely voice that commands attention, even when softly expressing bits of harmless small talk.

A first date to end all first dates: Showing the lovely Kitty Langley around Scotland Yard’s Black Museum.

A first date to end all first dates: Showing the lovely Kitty Langley around Scotland Yard’s Black Museum.

Fans often complain about George Sanders’ flattened affect in this film, but his very persona brings a default sinister undercurrent to every role. He is not particularly convincing as a police officer investigating the crimes — very few of us would expect George Sanders to take so long to piece together the clews — but as Kitty’s beau, he works his native charm to great affect, using it to overwhelm a mostly-hidden menace… mostly hidden.

There is a really clever bit of manipulation of audience expectations in the character of Robert Bonting, played with charming subtlety by Sir Cedric Hardwicke. Bonting is fascinated with the Ripper killings, poring over the special editions constantly and proffering theories of his own. His wife later reveals to Slade that Robert lost his brokerage business which lead to a nervous breakdown and financial strain. He is also quite cross that they’ve taken in a lodger at all, sniping bitterly that he doesn’t want to lose his privacy. It seems a perfect set up for Bonting to be the character who suspects Slade, but he is immediately the voice of reason, such as it is, explaining Slade’s odd behaviors away while engaging in some oddness of his own.

It is this that makes Bonting suspicious, and the audience wonders, even if only slightly, if there will be a twist ending and he will be unmasked as the Ripper after nearly 90 minutes of assuming Slade is the killer. This secondary suspicion is encouraged by the memory of the Hitchcock version, of course, where the lodger very famously is discovered to not be the killer at all.

Gaslight as the flames of Hell: A glimpse of Kitty through the eyes of Mr. Slade.

Gaslight as the flames of Hell: A glimpse of Kitty through the eyes of Mr. Slade.

If the crimes of Jack the Ripper were so distant as to be essentially fictitious to 1944 audiences, so too would have been the world of the 1880s. Gorgeous and complicated outfits, lavish stage shows, fussy Victorian parlors and flickering gaslight recalled a world just past recent memory. Like half-seen shadows at night, it would have been a strange and confusing world, making the audience a social trespasser in the same way Slade is.

“I am, after all, a grotesque.”

“I am, after all, a grotesque.”

Laird Cregar quoted in an interview, 1944

The Lodger is unquestionably Laird Cregar’s movie, his psychological removal from society blaring from every distant camera angle, shadow, and frame that sometimes only captures a small part of Slade as though it were trying to exclude him from the very movie he starred in. Slade struggles constantly with an internal compulsion to do what he feels he must versus what he wishes he could do. Like the Dr. Jekyll he so obviously emulates, Slade’s life is split, compartmentalized through necessity, much like Cregar’s own life must have been.

Much is made of Laird Cregar’s looks. He was nearly 6’4″, about 300 pounds, stuffed into an ill-fitting suit and a far cry from the usual matinee idols of Hollywood. Yet Cregar could not have engendered sympathy from the audience had he not been attractive on some level; by attractive, I mean he literally attracted viewers to him, to his plight and his goals, as psychotic as they were.

Merle Oberon in later years dismissed The Lodger almost completely. She was upset by the war and ill health, she said, going on to claim she was forced into a part she didn’t want and didn’t care about. It’s possible that Oberon was distancing herself less from the film than her somewhat infamous treatment of Laird Cregar. Thinking she was being supportive, Oberon had told him if he just lost weight he could become a leading man, a real star. The words hit the lonely, troubled Cregar with a tangible thud. His looks and sexuality forced him to the outskirts of Hollywood society, seemingly forever thwarting his childhood plans of being a leading man. He felt cheated out of juicy roles like Waldo Lydecker in Laura (1944) and Lord Wotton in The Picture of Dorian Gray, denied him because he was already typecast as the heavy heavy, a younger and more mentally unstable version of Sydney Greenstreet.

Further, just prior to filming The Lodger, Twentieth Century Fox’s Darryl Zanuck had scolded Cregar for not hiding his homosexuality. Laird often accompanied his dancer boyfriend to well-attended shows. In 1943, the dancer was found murdered in a bathhouse, and Laird openly told newspapers of his friendship with the victim and sorrow at the tragedy. Zanuck hastily scheduled faux dates for Cregar with starlets, including Dorothy McGuire, to try to cover what he felt was an indiscretion on Cregar’s part.

Already in a difficult place, Cregar plunged himself carelessly into the role of Slade, his 15th role in a career just this side of four years old. Protecting himself emotionally was not his concern; he identified with the sexually confused serial killer Slade and made no attempt to hide it. His good friend George Sanders worried about him throughout the shoot, especially when, after Oberon’s encouragement to diet and Zanuck’s encouragement to just stop being gay already, Laird Cregar announced that he would become a thin, romantic leading man. He began to date women seriously and stopped eating.

Periods of starvation were not new to him, nor was complete immersion in a role. But something about The Lodger escalated Laird’s resolve to transform himself. When he was passed over for Dorian Gray, he took a role in Hangover Square, an odd film in that it is almost entirely a remake of The Lodger, done only months later and with many of the same actors. After losing over 100 pounds in less than a year, Cregar had plastic surgery to alter his facial features. When filming on Hangover Square was completed, he underwent voluntary gastrointestinal surgery to help him lose more weight. In the 1940s, bariatric surgery was in its infancy, and Cregar’s body was unable to handle the physical strain of the surgery. His heart gave out during post-op recovery. He was 31 years old.

In less than two years, a new “heavy heavy” emerged, actor Raymond Burr. When erroneous reports surfaced that Burr was Cregar’s younger brother, Burr did nothing to dissuade people from the idea because it won him roles that Cregar would have had, had he lived. By the late 1940s, it was as though Laird Cregar was never even here.

Slade emerges, fully-formed, from out of the London fog.

Slade emerges, fully-formed, from out of the London fog.

The character of Slade is beyond confused, at least sexually. He looks with disgust upon actresses, though there is also covetousness in his eyes. He is not merely repressed, though, as the film reveals small verbal hints that he might be gay, not as blatantly as in the Hitch original but still clear. When Slade brings out the portrait of his brother it is in direct contrast to the portrait in the 1927 silent, where the audience wondered if the woman was not the lodger’s sister but rather the victim of his psycho-sexual crimes. The same assumption would be made with Slade and his brother, hinting at both homosexuality and incest. Later, Slade’s remarks about the women he had killed mark him as a necrophiliac. Between The Lodger and Laura, 1944 was a banner year for necrophilia, though Cregar had engaged in villainous love of the dead three years earlier in I Wake Up Screaming (1941).

The Lodger is as split in personality as its central character. It is both heavily influenced and influential, a remake and an original interpretation, with B-movie sensibilities and an A-level final product. Those few in the audience in 1944 who were of an age to remember the real 1888 murders must have regarded them, in a sense, as less reality than bad dream, and though the film is historically accurate in regard to the crimes, the Ripper is no more real than the fictitious characters of classic horror that are referenced throughout. Though a remake of an Alfred Hitchcock film, it is not a film Hitch would ever have made, and that is exactly as it should be.

Sources:

Hollywood Cauldron: 13 Horror Films From the Genre’s Golden Age by Gregory William Mank

Broken Face in the Mirror by David Hernandez

Smirk, Sneer and Scream by Mark Clark

Stacia, as a Laird Cregar fan, I was especially interested in your BEST HITCHCOCK MOVIES (THAT HITCHCOCK NEVER MADE) blog post about the 1944 version of THE LODGER, and it was as fascinating and moving as I thought it would be, from performances to art direction! I was especially glad you delved deeply into Cregar’s short, difficult life. Now that I know Merle Oberon gave poor Laird the idea to go on the crazy crash-diet that helped to kill him, I wish I had a time machine so I could find her and punch her out! I agree that Cregar’s performance as the mysterious, tormented Slade is the is the film’s biggest asset (no weight puns intended!), with his poignant yet unpredictable portrayal. He was far from the cardboard cliche villain, and that’s what makes Cregar’s performance so memorable. I also very much liked your discussions of archetypes of prostitutes and “the almost surreal normalcy” of the other characters around him. BRAVA on a stunning post, Stacia, and thanks a million for joining us in our Blogathon fun! Drop by anytime! :-)

P.S.: If you’re interested, here are more Laird Cregar items from Team Bartilucci you might find of interest:

http://noirbabes.com/film/2012/06/16/spotlight-on-laird-cregar/

http://doriantb.blogspot.com/2010/10/flico-suave-analysis-of-suaveness-in.html

http://doriantb.blogspot.com/2012/06/hudsons-bay-eager-for-cregar.html

Thank you, Dorian! I will definitely check those posts out.

I really fell in love with Laird Cregar when watching this movie, and I now have a stack of them to see. The only other one I’d ever watched before The Lodger was Heaven Can Wait, but now I’ve seen several.

And sorry the comment had to be approved, I don’t know why WordPress wants me to moderate some of my comments. So confusing.

Don’t be too tough on Oberon – I mean, let’s face it, at that considerable weight, Cregar’s health would have been in serious jeopardy already.

Cregar is by no means the first person to die after rapid weight loss, and it’s improbable to believe he (or anyone) would have lost weight so quickly had society not been so judgmental. Oberon is, of course, representing society in that anecdote, prodding him to lose weight without even wondering if it was appropriate to do so, apparently without caring that she might upset him.

I dearly love Laird Cregar. If there really is a Hell, I’d like to think the guy running the place is the spitting image of Cregar’s urbane “His Excellency” in Heaven Can Wait (1943), which may very well be my favorite of his performances.

I like The Lodger, but my personal preference is for its “remake,” Hangover Square–which is a little more to my show-offy stylistic tastes. And yet you were able to whet my appetite to perhaps give The Lodger a second look-see, but then again you always end up doing that. Marvelous essay, kiddo.

Thanks! I was shocked at how much I loved the film when I saw it again. I’d just seen it about 3 months ago and thought being “spoiled” would dampen the cinematic mood, but not so. Give it another try if you get a chance.

I got the box set with Hangover Square and Undying Monster, so those will be on my agenda soon. But I’m kind of worried about seeing his final film, evidence of his inner deep insecurities all over the screen. It’s potentially really upsetting, and that’s the same reason I haven’t yet watched the Tony Hancock interview on the box set you got me. Between Pop Singer Who Shall Not Be Named (But Who Deserves An Ass-Whuppin’) and Breaking Bad, I am chock full of reasons to go clinically insane. No use adding more to the pile.

Loved your review of Cape Fear! I’m going to shout “Marv!” every time I see that scene again, too.

Doctor Who did an adventure titled “The Lodger” a season back, and I couldn’t resist having a bit of fun in my review at Newsarama –

“In a brilliant remake of the Hitchcock classic, funnyman James Corden takes on the role that made Laird Cregar famous as a madman who takes a room in…oh, hang on, I’ve just been told that this is NOT that story, it is in fact a Doctor Who episode.”

Ha! That’s hilarious, very Monty Python and I love it.

I keep meaning to get into Doctor Who, then forgetting, and I have no idea why.

Very interesting and well done post. Not having seen the earlier Hitchcock film, I now want to see it very badly! Laird Cregar’s story is such a sad one, but he is always unforgettable, especially in this movie.

Thanks! I really like the original Lodger. It has some of that wacky too-fast editing that might have been original, maybe was from a pieced-together copy, who knows. That was distracting, but otherwise it was quite good. Ivor Novello was terrific in it.

Really enjoyed your detailed post Stacia, well done. I saw HANGOVER SQUARE several times before remake of THE LODGER, which for some reason used to turn up much less frequently on British TV (This may be why I prefer it in some ways – that and the wonderful Bernard Herrmann score). Indeed I saw UNDYING MONSTER before THE LODGER too come to think of it – don’t know if there was a rights issue over the original novel perhaps? Nice that they were all collected together in the same box set as they clearly showcase director John Brahm’s gift for expressionist technique.