This entry is for Garbo Laughs’ Queer Films Blogathon, held June 27. Because my post ran long, I put this part up early and posted the second half Monday, which you can find here.

The Clara Bow talkie Call Her Savage (1932) is less a movie than a checklist of sexual situations designed to attract viewers to the most sordid spectacle Fox Film Corporation could commit to film without being hauled in front of a panel of angry U.S. senators. After a series of events that include Clara wrestling with an enormous mastiff determined to rip her already barely-there blouse off and a breast-grabbing catfight with Thelma Todd, the appearance of the gay singers at a rough nightclub is no more than another implied perversion to add to the list of Clara’s “throbbing adventures.”

The prevailing modern opinion is that this is a gay bar, but that’s (probably) incorrect. The floor show is actually a pansy act, popular entertainment during the 1920s and early 1930s The Pansy Craze. Risque gay-themed songs and performers in drag were called pansy performers and were very trendy in underground clubs such as the one pictured in Call Her Savage. The club they go to does not show gay patrons specifically; rather, we see male patrons gaping and groping Clara (one gets slapped for his efforts) and we’re told it’s a bar for “wild poets and anarchists.” The hostile speech Mischa Auer directs at Clara’s companion is a common portrayal of an anarchist and/or socialist during that era. No, it’s not a gay bar, but an underground club with so-called pansy performers.

Interestingly, actor Tyrell Davis appears in Call Her Savage briefly as the rich man the savage Nasa Springer’s father wants her to marry. Davis spent most of his brief career playing the effete man whose sexuality, at least in many pre-codes, was completely undisguised.

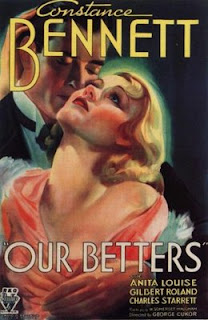

Davis’ next film after Call Her Savage is the one he is most known for today, Our Betters (1933). This deliciously bitchy satire skewers the upper class, all of whom in this film are rich Americans pretending to be so far removed from the classless United States they were raised in that they no longer remember how Americans speak… or so they claim. Witty and full of both subtle and blatant innuendo, the gathered party hits a snag when Lady Grayston is caught dallying with Duchess Minnie’s kept man. Forced to keep up appearances, Lady Grayston must try to prevent the Duchess from leaving before the weekend is over. Lady Grayston tries everything she can, but doesn’t fully succeed until she brings the divine Mr. Ernest, society dance instructor, to her home. The Duchess has been wanting lessons from the fabulous Ernest for weeks and is persuaded to stay at Lady Grayston’s when he arrives…

…in fabulous make up, “just as I am!”

…in fabulous make up, “just as I am!”

Tyrell camps it up to heights you never thought possible in a 1933 film, and even utters the now-famous final line when the Duchess and Lady Grayston make up: “What an exquisite spectacle! Two ladies of title, kissing one another!”

While Ernest is played for broad humor, character Thornton Clay is not. This unmarried social gadabout is part of the elite inner circle, and Lady Grayston is what we would nowadays call his hag, as they frequently attend theatre and other outings together. If one was unsure of his sexuality, the Duchess outs him toward the end of the film. She complains that, if Lady Grayston absolutely had to have an affair, why not with Thornton since she was with him all the time anyway?

Lady Grayston raises a knowing eyebrow while Thornton has a mild panic, eventually protesting that the subject has become unnecessarily personal.

Tyrell Davis’ film career all but ended after the Hays Code was implemented, as he specialized in obviously gay characters who could no longer be portrayed openly. Meanwhile, other character actors who could pull off the is-he-or-isn’t-he ambiguity required by the Code flourished. One such actor, of course, was Edward Everett Horton — and where would this post be without the amazing Eddie Horton, anyway?

Horton spent most of his career portraying ambiguously gay characters, the kind of men who humorously have their sexuality and masculinity questioned, yet his characters often pursued women while being called gay… or called everything that could imply gay without anyone actually saying the word “gay.”

Horton’s role in the pre-code Roar of the Dragon (1932) is exactly that type of character. RotD is an obvious attempt to mimic the early 1930s trend of Orientalist action films that depict Asians as having an evil, exotic nature. The film may play like a low-rent Shanghai Express with Gwili Andre as a bargain basement Dietrich, but star Richard Dix puts in a solid performance. Dix plays the drunken ship captain charged with trying to get a group of tourists and Chinese toddlers out of a hotel surrounded by gun-wielding bandits. Horton meanwhile portrays mild-mannered Busby, the meek hotel clerk who declares his intentions of marrying a lovely chorus girl staying at the hotel. When he does so, she calls him weak while Dix sarcastically snaps, “My, what a rough daddy you’ll make.”

Yet Horton’s role takes a different and unique turn when the chorus girl is killed by attacking bandits. Enraged, Horton heads straight to the machine gun to mow down some bandits in revenge.

And he does a good job, too, killing dozens of the bad guys and ending up as the captain’s sidekick when he stays behind with the captain as a diversion while the others escape. Busby’s change through the film is played like a gay-to-straight bildungsroman, a transformation from a homosexual/emasculate to a man who has earned his heterosexuality and manliness. However, this transformation is, perhaps unintentionally, interrupted at the very end when Busby is shot and lays in the arms of the captain:

The captain can’t bear to leave his dying friend behind, so he risks everything to carry Busby to the escape boat. It’s a scene that is remarkably touching, far more so than a usual buddy moment between two male friends. The captain at the end of the film is more concerned with his new-found friend than the blonde damsel in distress he had been sleeping with for the first hour of the film. Yet for all that, Busby’s last lines in the film blatantly reassert his heterosexuality, reassuring everyone that he died a man.

The film doc The Celluloid Closet deals extensively with the portrayals of LGBT characters in films, especially with the 1930s and 1940s portrayal of sissies, the coded version of gay men. While some obviously feel the portrayals are universally bigoted and inappropriate, with the heaviest condemnations from Gore Vidal and Arthur Laurents, interviewee Harvey Fierstein puts voice to another perspective, that the sissies helped achieve “visibility at any cost,” that it was better to have negative portrayals of gays than none at all.

It’s an idea that could be debated for a lifetime. While I agree that “visibility at any cost” was important, at the same time, the negative portrayals were not harmless. Note that Fierstein did not say that they were, but an argument that is frequently put out there, at least on the internet, is that any bigotry portrayed for humor was harmless because “it was just that way” and “most people didn’t catch the gay references anyway.” It is an absolute mistake to believe that audiences in the 1930s had no idea about homosexuality, that only the most overtly gay characters were recognized as gay. While film may have been held to a standard that limited portrayals of sexuality, there was much less restriction in the art and literature worlds. Numerous authors, painters, and philosophers addressed homosexuality both in their work and in their real lives, and of course there is always gossip in the tabloids or in the real world. It’s that experience that those who wrote dime novels or pre-code salaciousness counted on. An audience’s familiarity with sexuality, including the overall concept of homosexuality and associated stereotypes, is what made the coded gay characters effective. There was no reason for anyone to create a character in the mold of sissy, confirmed bachelor, or domineering woman in man’s clothes unless the audience was expected to understand what the implied meanings were.

Celluloid Closet makes the claim that, after the Motion Picture Production Code came in, gays were seen exclusively as “cold-blooded villains.” Unfortunately, that’s far too sweeping of a statement to be true. Before the Code, homosexuality was part of Hollywood films but rarely in a positive light. Gay men and women were included either as titillation, cheap laughs, or an added layer of “wrongness” to a villain.

The 1932 films Island of Lost Souls was the first film to feature the character Dr. Moreau, a vivisectionist who has secluded himself on an island after being run out of England, here played by the exquisite Charles Laughton. Moreau is continuing his horrifying experiments on animals when Edward Parker, a man rescued from a sinking ship, arrives on his island. Moreau is eccentric, charming and unusually observant of social mores and propriety, especially since he runs an island dedicated to the unanesthetized surgery of animals to form them into human-like beings.

Moreau immediately shows interest in Parker, with his unwavering stares and frequent lingering up-and-down looks at the new arrival. It’s to Laughton’s credit that he creates Moreau as such an intense personality that these looks come across as subtle because they are often focused elsewhere, but always to other things or something happening off screen; the only person he has those eyes for is Parker.

Moreau has created what he feels is his most human-like creature, a panther transformed into a human woman, but he wants to know just how human she really is. He puts Parker and the Panther Woman in situations together to see if they will be attracted to each other. Parker has hated Moreau from the beginning but doesn’t know the entire story behind the strange doctor, so he demands an explanation as to what is going on. Moreau informs him that the woman is actually a panther whom he was hoping to get Parker to mate with. As he explains, he moves in closer to Parker, advancing, his eyes twinkling and solid; Moreau’s unmistakable glance downward as he says the Panther Woman was “attracted to you” makes it clear that he, too, is attracted to Parker.

His advances are met with a brutal punch that throws him across the room. It’s seen as justified, of course. Parker knew Moreau experimented on animals, and as he’s told that the doctor was hoping to trick him into having sex with a panther made to look like a human, he seethes, but the breaking point is that look, that blatant come-on, and that’s why he attacks Moreau. In pre-code horror, as the evils done by the villain escalate, films often added a little gay into the mix to put that edge on the “wrong.”

There is another fine example from 1932, White Zombie starring Bela Lugosi as voodoo master Murder Legrande. When beautiful Madeline arrives on the island to marry her beau, a jealous and captivated Charles Beaumont begs Legrande for something to make her leave her husband on her wedding night and go to him instead. Legrande agrees, and Madeline becomes Beaumont’s zombie sex slave — not flatly stated, of course, but the implication is more than clear, as the nude woman “Performing his every desire!” in the poster will attest. When Beaumont realizes that sex with a dead-eyed, soulless woman is not all it’s cracked up to be (who knew?), he asks Legrande to give her an antidote to make her human again.

Legrande decides to keep her for himself… but he also decides to keep Beaumont. He gives him the same potion given to Madeline, and as Beaumont slowly realizes he is going to become a zombie, Legrande tells him with a smile: “I’ve taken a fancy to you.” Not merely zombiedom for you, Beaumont, but zombie sex slave just like Madeline. Welcome to karma, my friend, and enjoy the ride.

It wasn’t only pre-code horror that used homosexuality to add more sinister layers to the bad guys in movies… but we’ll get to that in the second half of this post here. Please, don’t forget to check out all the entries by going to Garbo Laughs on Monday the 27th. Carolyn has dedicated the entire month of June to queer cinema, too, with plenty of amazing entries that are all highly recommended.

***

Call Her Savage “throbbing adventures” poster courtesy D for Doom. Roar of the Dragon poster and Eddie Horton with Carmen Miranda courtesy Doctor Macro.

What a very interesting article, I can’t wait to read the second part. I study action hero films for a summer class and we delved into the definition of ‘camp’ in terms of having homosexual characters in early action movies (think the two hench men in ‘diamonds are forever’)without labeling them as such. Do some of these characters fall into the ‘camp’ category? I’m interested in hearing your thoughts. Again, love the article

I have to say that I’m not fully versed in when camp or kitsch really came to be seen as a recognizable film genre — I believe Minelli’s The Pirate was intended to be camp but was ahead of its time in that no one really recognized camp the way we do today, IIRC. If so, then all the movies I spoke about were way before camp would have existed in the modern definition.

That said, Mr. Ernest in Our Betters is 100% campalicious, as are the pansy performers in Call Her Savage, but frankly that entire movie is camp on the level of Valley of the Dolls. Ernest and Call Her Savage were intentionally portrayed this way, but unintentional camp can be found in Bela’s performance in White Zombie too.

Nothing quite on the level of the henchmen in Diamonds Are Forever though. Those henchmen were obviously gay but also created specifically to be ridiculed, and that’s not quite the same as making a villain gay so he’s more evil, or trotting out gay stereotypes to amuse the heteros.

A very interesting look at early depictions and how the Code has really come to define what “Old Hollywood” was, despite the fact that it was created because Hollywood was getting too liberal. Thank you for your contribution!

I enjoyed this article and especially your take on Island of Lost Souls. I read that punch the same way you did, and I think it was Laughton’s own homosexuality that made his characterization serious, though one could argue that being the villain of the piece, he reinforces the evil homosexual type.

Not merely zombiedom for you, Beaumont, but zombie sex slave just like Madeline. Welcome to karma, my friend, and enjoy the ride.

I’m going to be laughing at this for the rest of the day.

Thanks again Caroline!

You bring up an interesting point, Marilyn. Laughton was closeted enough that he remained married to Elsa, and Maureen O’Hara still claims he was straight and attracted to her, yet he had no problem playing roles like Dr. Moreau. I get the impression that he relished being able to play gay in film, even if it was the evil homosexual, and it may have really suited his artistic temperament. At that time, could any gay actor be blamed for playing to broad, harmful stereotypes? I don’t really have an answer for that, it’s one of those questions I think about but can’t fully resolve.

Thanks Ivan. I love that part of the movie so much, because we almost never see a man who wants to take a woman who doesn’t want him get exact eye-for-an-eye retribution.

Wow, great post!

I’d never seen that aspect of the subtext in ‘White Zombie’, being hung up on a more economic interpretation. Awesome insight there, and beautifully written.

Thanks David! I admit, I am always on the lookout for the gay subtext. Several years ago I watched Gilda, saw the less-than-sub subtext, and I can’t stop looking for it now.