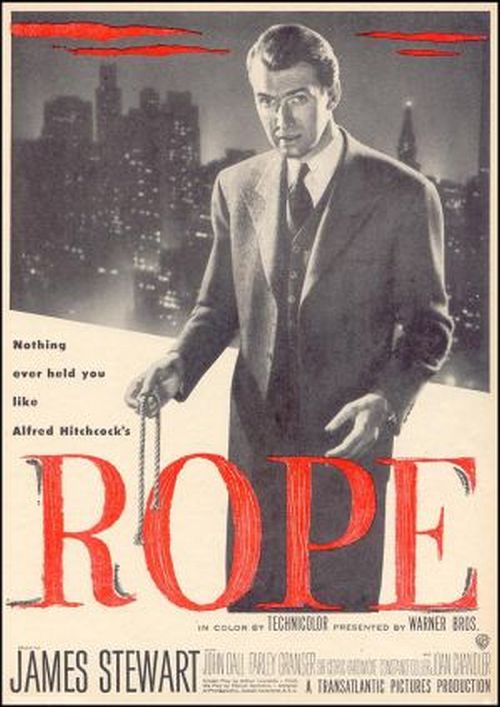

This article on Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) is the SBBN entry for the 2012 For the Love of Film Blogathon, dedicated to raising funds to allow the 1923 film The White Shadow, much of which has recently been found in a New Zealand archive, to be shown online. More about this project can be found at This Island Rod, who is also today’s gracious host of the blogathon. For more links to this year’s participants, please visit his blog which will also have links to Ferdy on Film and Self-Styled Siren, who share hosting duties and who listed all the ‘thon participants earlier in the week.

For a host of details about the restoration, I very much recommend The Smithsonian Magazine‘s article and blogathon entry here.

Please consider donating! Click here to donate or click the banner to the left. Any amount can help. Think of it as your ticket price, where your ticket buys you the chance to see the restored The White Shadow (1923) online in the comfort of your own home, eating Funyuns and clad in paint-spattered sweatpants and those adorable Snoopy socks that are comfy but, frankly, are so old they’re only held together by three tenacious sock molecules who are not yet ready to die.

And on the subject of dying we gracefully segue into tonight’s episode, a sordid little tale of two young men and their intellectual curiosity, which kills not a cat but a man, whose lifeless corpse is tastefully hidden away in an impromptu buffet table from which his friends and family unknowingly feast.

“[Hitchcock] was like a child who’s just discovered sex and thinks it’s all very naughty.” – Arthur Laurents, screenwriter, Rope

The immaturity of Alfred Hitchcock’s attitude toward sexuality has been generally criticized, both during the years he actively worked on films as well as in modern reviews. What many consider a fault in Hitch’s oeuvre is something I find fascinating, even charming. I love that the maturity shown in the control of his craft is in such bleak contrast to the immaturity of his interpersonal relationships. The messiness of his insecurity and sexual curiosity is splattered all over his films, some more obvious than others, and while it’s deeply personal it also reflects the same sort of semi-hidden Puritan values many in the Western world identify with.

The relationship between upper crust university students Brandon (John Dall) and Phillip (Farley Granger) in Rope could hardly be more explicit. Their dialogue and shared looks are transparent, and there is of course the little matter of the chicken-choking anecdotes. Hume Cronyn, who adapted the play for the screen, stated that Hitchcock wanted the relationship between Phillip and Brandon to be blatant, and while overt mentions were impossible, darkly comic hints were not. Scattered amidst the jokes about Strangulation Day are less obvious jokes about sexuality.

Phillip is the one who strangles David with the titular rope at the beginning of the film. Once the guests arrive his partner Brandon, carried away with his private jokes about the murder no one else has discovered yet, tells a story about Phillip trying to strangle a chicken on an upstate farm as a teen. In 1948, this must have been a naughty pun but not likely an overt reference to the juvenile term “choking the chicken.” It is so blatant now that it is almost shocking and certainly very funny, at least to someone like me who has a rather unkind and perverse sense of humor. There is a question of whether “choking the chicken” was even a slang term in 1948, though The Journal of Folklore Research notes that many languages use birds as slang terms for the penis, going back to the word for sparrow in Latin; further, the German “vögelin” means “to bird” which, in turn, means “to fuck.”

Even if the specific phrase was not in use in 1948, the symbolism would have been easy to suss out. By calling attention to Phillip’s history of strangling chickens, murder is bluntly equated with sex and masturbation. That is not a surprise, given the opening lines of the film are undisguised pillow talk between Brandon and Phillip immediately after David’s murder. It is a surprise, though, when their former private school housemaster Rupert Cadell (James Stewart) reminds Phillip that he knows he is “quite a good chicken strangler.” It is not the fact that the two are gay that is shocking, it’s that a man obviously decades older than the teenage Phillip would abuse his position of authority so cavalierly. Yet his blithe pronouncements that some men were meant to judge humanity based on self-presumed moral superiority was abuse of power, too. Rupert metaphorically reminding Phillip of their sexual past is just another reason to believe these boys were raised, perhaps inadvertently, perhaps not, to be murderers.

What is intriguing is that, despite the relatively blatant portrayal of homosexuality, it is not used as a reason for psychopathy. After the crime is revealed, Rupert starts his nervous lecture and mentions repeatedly that Brandon and Phillip are evil, but without a single euphemism to indicate being gay is part of what made them evil. Given the script is packed to bursting with puns, darkly humorous turns of phrase and immature metaphors, there is a startling lack of such innuendo in the finale. This change of tone in the script feels deliberate, done to prevent any unnecessary equating of sexuality with psychopathic behavior.

Hitch has an obvious curiosity about sexualities he has not experienced, but he doesn’t seem to think of it as “nasty” or judge with the “Victorian Catholic background” as Arthur Laurents once said, at least not in Rope; later films like Marnie and Frenzy are another matter. But perhaps Hitch simply had not been able to confront his own inner judgment on sexuality until later years and thus, in films like Rope, simply discarded the notion altogether in the final scenes rather than face it.

The man walking along the sidewalk early in the film is often credited as Hitchcock in his expected cameo, but the man does not walk like Hitch and I’m not convinced it’s him. The cameo is also said to be a red neon sign in the skyline outside the apartment window, a sign which is supposed to be the famous Hitch caricature in an ad for “Reducto,” the fake weight-loss product. It took quite a bit of convincing to make me believe that was really the caricature, primarily because it is so difficult to see. Yet on this viewing I was finally convinced, and for a rather silly reason: The decorative horse-cow-thing resting on a couch to the right of the advertisement is moved after a reel change so that it blocks the neon sign. The sign is quite large and distracting, so obviously after it had done its job of cameo-by-proxy, it needed to be diminished but could not be removed because of continuity.

of convincing to make me believe that was really the caricature, primarily because it is so difficult to see. Yet on this viewing I was finally convinced, and for a rather silly reason: The decorative horse-cow-thing resting on a couch to the right of the advertisement is moved after a reel change so that it blocks the neon sign. The sign is quite large and distracting, so obviously after it had done its job of cameo-by-proxy, it needed to be diminished but could not be removed because of continuity.

The so-called gimmickry of Rope — the attempt to make the film appear to be one unbroken take — is frequently cited as the film’s main flaw. However, I find the palpable miscasting of Jimmy Stewart as Rupert Cadell to be far more damaging to the film than any technical tricks. What the performance of Rupert needs, what it so desperately desires, is an actor who can manifest all the conflicting, simultaneous emotional agendas roiling inside an ultimately selfish man. For all his alleged acknowledgement of his contribution to the crime, Rupert crucially wants only to distance himself from the murder. Like the closet sociopath he is, he’s operating only on the first level of Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development: Avoidance of punishment. To that end, Rupert immediately reminds the pair that he is superior to them; he may have engaged in theoretical discussions and hypotheticals but he, being a member of the human race, could never have done such a thing. Or so he claims.

What becomes clear in the finale is that Stewart does not understand, or at least cannot convey, that Rupert’s imagined superiority over fellow human beings is precisely what lead that sad trio (quartet, actually; we can’t forget about David) to that distancing final shot of the film. Falling back on the superiority argument only highlights that fact, but because of Stewart’s take on the role, this parallel appears only in words, not in realization.

Rupert’s closeness to the boys is unquestionable. We know what Rupert has taught them philosophically and sexually, and we know how flippant Rupert is on the subject of murder. That is why he cannot be convincingly played straight as a man wronged, as a father figure misunderstood who now realizes the errors of his personal philosophy, yet that is exactly what Stewart does.

Stewart, I think, must have known his performance did not squarely match either the rest of the ensemble or the tone of the script. He is visibly nervous toward the finish, and like the professional he is he uses it to advantage, shaking as he discloses the rope from his suit pocket and imbuing his chilling last lecture with nervous pacing energy. Jimmy Stewart flounders to find the character of Rupert just as Rupert flounders for excuses to distance himself from the murderers. But the performance is not convincing, neither as desperate self-defensive bluster nor the justifiable rage of a man wronged.

The cast of Rope is fantastic, James Stewart notwithstanding. John Dall is smug intensity personified, playing Brandon as someone who truly believes he’s the charismatic center of attention, unaware that everyone else regards him from a cool, safe distance. Every hair on his head and every stitch on his suit is impeccably placed, tailored for maximum effect. Phillip is the more emotional of the two, well-groomed but without sharp-edged suits like his partner, his hair professionally mussed in that delightful late-40s way.

Sir Cedric Hardwicke is a master of understated pathos. He is subtle but quite touching as the father worried about his son, and worried about the souls of those around him who seriously discuss their moral superiority which they believe allows them to decide who lives and who dies. I really enjoyed Joan Chandler, whose cool delivery paired so well with her big, innocent eyes. Every time I watch this film, I wonder again why she didn’t have a bigger career.

Hitch very likely approached Rope with a self-awareness of his own culpability in presenting murder as humorous and justified, exactly as Rupert does. Rope takes the metaphor of Hitchcock’s movies “teaching” young people that murder is sometimes justified to a rather illogical extreme, but in doing so does draw in the audience enough so that, at least subconsciously, they began to question their own tolerance for stylized (and stylish) killings.

The technical aspects of Rope are the most talked-about aspects, which is a shame because the final product is far less gimmicky than its reputation suggests. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times was even more contemptuous than usual, claiming that the story was dull and bare while at the same time admitting to be frankly upset by its morbid, explicit nature. It’s difficult to reconcile Crowther’s feeling that a film which was “frightfully intense” was also boring.

Hitchcock apparently loved the technical challenges of filming Rope to look as though it was one single long take, and was apparently inspired by a similar technique used on the 1939 television version of the play. In the 1962 interviews with Francoise Truffaut, Hitchcock at first seems reticent to talk much about Rope, and when he does it’s entirely about the technological feats achieved in filmmaking. He dismisses the technique a “nonsensical stunt,” though, a “mistake” that he made again in a few scenes of Under Capricorn. He is also defensive and in denial with Truffaut, saying that Rope was generally liked by critics which is, unfortunately, not true.

Gene Siskel repeatedly stated that there were no cuts in the film, which is patently untrue; there are edits in the film where the camera cuts to another area, and while movie watchers are so used to edits that we don’t even react to them, if one is going to state on national television that a film uses no conventional edits then one should, perhaps, actually check to see if that is true instead of announcing it while a sidekick repeatedly chuckles condescendingly.

It is true, though, that the technical aspects of the film meant actors had to be at the top of their game, to know their lines verbatim for takes of up to 11 minutes while maneuvering through a set covered in cables and props on wheels. This was unheard of for actors. Despite the many comparisons of this movie to live plays, stage actors had more freedom of performance than what was required on Rope. Some of the behind-the-scenes publicity photos are absolutely startling:

The actors are dwarfed by the technology and outnumbered by the crew.

The actors are dwarfed by the technology and outnumbered by the crew.

Hitch is right in their face during filming, almost part of the scene himself.

Hitch is right in their face during filming, almost part of the scene himself.

Cameras on tracks and cords moving from one pre-planned, marked area to another capture the feel of a single-set stage play, yet there is a lot of bounce to the camera movement, resulting in many shaky scenes. Shadows from the crew can be seen gliding over actors as the enormous camera slides in. And honestly, it seems odd that Hitch would attempt to create a film that deliberately eschewed the technical methods that define film and set it apart from other arts. He went so far as to try to reduce the color in the film to a mostly grey palette, though he also was insistent that he film in Technicolor and was excited to make his first color film.

The grey tones are effective in Rope though a bit obvious. Hitch would refine this color palette over the years, using it to much better effect in films like North By Northwest. And just as Eve Marie Saint’s red rose gown stands out amongst the grey of everyone about her, Joan Chandler’s intense maroon dress brings the focus on her. Perhaps Adrian had an off day or perhaps this is personal taste, but I always felt Chandler’s dress was a bit of a joke, a fashion writer impeccably made up but in a gown of dubious taste. The poufy shoulders are one thing, but poufy elbows are quite another.

In Rope, appearances are more important than human beings. The characters are deliberately crafted like expensive hand-made chess pieces, the elegant apartment the playing board. The film is exciting while we watch how those pieces are played, and falls into tedium when Rupert suddenly converts to a pro-humanity stance, demanding Phillip and Brandon — and us, by extension — cease treating human beings as though they were objects. And had Hitchcock been as interested in the story as he was in how to film it, we might have gotten more insight into how Hitch himself reconciled his dehumanizing filmmaking techniques. Then again, this is the man who famously said that all actors should be treated like cattle. Perhaps there was never anything inside Alfred Hitchcock that needed to be reconciled at all.

It always seemed to me that the less-than-subliminal hysteria Stewart brought to his role, especially in his final speech, indicated that his character was a closet case himself; you do wonder why this middle-aged bachelor is hanging around the apartment of two former, highly attractive, younger students. Rupert may be more of a hypocrite than he’s aware of. Interesting that, as you point out, the final speech doesn’t connect homosexuality as a component in the murder; but then, if Rupert shares the two murderer’s sexual preferences, he might have to distance himself for that additional repressed reason. Enjoyed your post!

This is one hell of a review!

Wonderful essay! As Usual! I actually liked Stewart’s performance, it had that creepy air of a ‘kapo’ realizing his complicity in his own eventual destruction, closeting his real self from his pretend one.

I loved Joan Chandler in this one, she had a strangely brittle sexuality at play, and seemed to be playing a perfect beard if someone needed one. I find interesting that she was Humoresque, as well.

Thanks guys!

I also thought Rupert was closeted for the first few viewings, but when I noticed on this viewing that he bluntly said he knew Phillip could strangle chickens I decided he really couldn’t be closeted. It’s possible that Rupert didn’t realize it was a metaphor and accidentally outed himself, though.

Joan Chandler has the Hitchcock cold, doll-like look down — the fussy perfect hair, the smooth-as-china complexion, the clipped voice. She should have been in more Hitchcock films at least, but she wasn’t blonde and he had such a thing for blondes.

Nice analysis, although I really do think the gay theme is–or at least WAS–less obvious than you argue. I’ll have to watch it again and see what I think of Stewart after reading this….

See. This is why you shouldn’t stop.

I think Stewart was certainly capable of pulling off the maniacally psychotic, obsessive whack-job, as he later let ‘er rip for Anthony Mann (and later for Hitch in Vertigo), he can’t quite pull off the narcissistic smarm needed for Rupert. (Can you imagine Dall in that role? Now THAT would have been something.) Like a lot of mega-stars of his strata, Stewart, seldom called on do nothing more but be Stewart, is under-appreciated for the range he could bring. I know there was a period after the war where he had trouble getting back into the acting swing. Maybe, here, he just hadn’t found his comfort zone again yet.

Who would you have cast as Rupert?

Off the top of my head, George Sanders, Clifton Webb or Vincent Price.

It’s possible that the gay subtext was a lot more sub than I thought, though even when I first watched Rope I was absolutely stunned and honestly delighted by it.

George Sanders as Rupert would have been almost too obvious, though I think he would have loved the role. I keep coming back to two later Hitch smarm-meisters, James Mason and Ray Milland.

Really need to see this.

Ooooo, yeah, Mason. You win.

Really enjoyed the analysis, thanks for all the detail. The non-disguided cuts were very strategically timed to allow cinema projectionists to switch from one reel to the next (i.e. the occur every 20 minutes or so) as, unlike the disguided cuts (someone passing in front of the camera or focussing on an object) which occurr not at reel changes, those that did could create problems of focus when shifting between one projector to the next.

Interesting stuff, Sergio. I had heard that the cuts that were disguised on the back of suit jackets and such were reel changes. I think Hitch says that in the Truffaut interview, but I just don’t remember for sure.

And I should mention Hitch wasn’t exactly truthful with many of his answers in the Truffaut interviews.

This is a great post! Reminds me that I need to watch Rope again :) I’m a big Hitchcock fan but have been forgetting it lately.

I watched this film for the first time for the blogathon so I really enjoyed checking out your take. I was especially intrigued by your suggestion above for James Mason as Rupert. I like it!

I really liked Joan Chandler and like you am surprised she didn’t do more.

Best wishes,

Laura