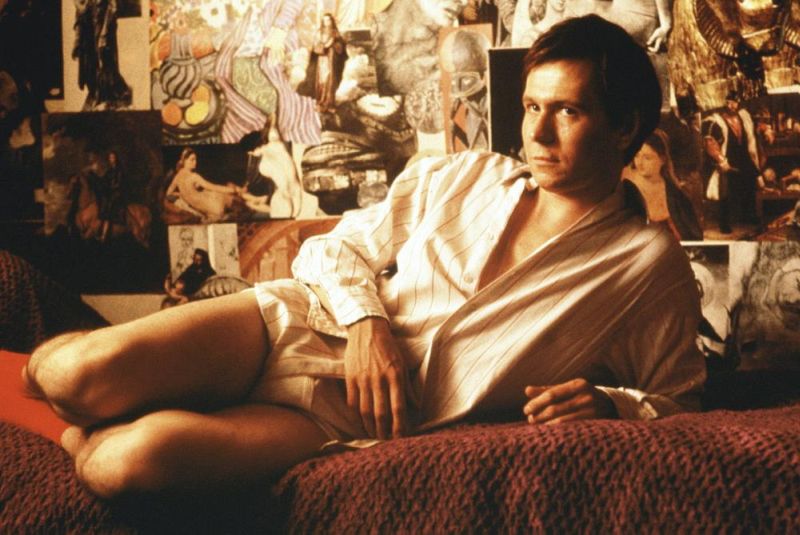

Gary Oldman as Joe Orton in Prick Up Your Ears (1987).

Gary Oldman as Joe Orton in Prick Up Your Ears (1987).

It’s the mid 1980s and biographer John Lahr (Wallace Shawn) is searching for the infamous diaries of playwright Joe Orton (Gary Oldman), hoping to learn more about the man he hopes to unmask in an upcoming book. Lahr’s agent Peggy Ramsay (Vanessa Redgrave) eventually gives him the diaries, and thus we are transported back to the 1960s, when Orton was the current darling of the theatre, a jaunty man with an insatiable libido and a neglected, neurotic partner, Kenneth Halliwell (Alfred Molina).

Prick Up Your Ears is based on the real-life story of Orton, who was brutally murdered in 1967 by his partner Halliwell, who killed himself with pills immediately after bashing Orton’s head in. Halliwell actually died moments after overdosing, while Orton lived for hours afterwards; his body was still warm when police arrived the morning after the attack. Though he had a short career, Joe Orton’s dark and cynical comedies paired with his outsized personal life — he was unabashedly out as a gay man during a time such a thing was not only unheard of, but could have landed him in jail for a very long time — have ensured his legacy.

Reviewers at the time reacted mostly favorably to Prick Up Your Ears, director Stephen Frears having impressed two years earlier with My Beautiful Laundrette, and Oldman having earned universal praise with his performance in the outstanding Sid and Nancy. His performance today might not impress as much as it did nearly 30 years ago, however, and for a very odd reason: Oldman has gone from being an impressive Hot New Thing ™ to becoming one of the finest actors of our generation, and his performances now far outshine what he did early in his career. Add to that the fact that the Orton character is such an irritating little smartarse, and that Oldman looks so much like Orton, right down to the questionable bangs, and it’s easy to inadvertently devalue what was, and remains, a fine performance.

That said, Molina’s performance was frequently devalued by the critics of the day, who I suspect would have seen any character who was a large, bald, neurotic gay man as being a freak no matter how he was played. Molina, however, gives a really fine performance, humorous and humane, which is a very eerie thing, considering what we know from both history and the very opening scenes.

As the film opens, we see Halliwell in dark close-up, his naked body covered in blood. It’s startling and confusing; he looks as though he were reenacting some long-missing footage of Brando from Apocalypse Now. We soon flash back roughly 20 years to Orton’s life — we never see Halliwell’s early years — as though the moment Orton as a young man decided to go into acting was the moment he sealed his fate.

A lot is done in the film to frame the murder as the inevitable result of a snot-nosed, amoral little jerk who stole his inspiration from a man he was unfairly leading on. In truth, Halliwell was far more disturbed than Molina’s portrayal indicates, though it should be said that the script does much of the work when it comes to this rehabilitation, intentional or not, of Halliwell. Also notable are comments in this article where Joe Orton’s sister Leonie and Daniel Kramer, the director of the 2009 play also titled Prick Up Your Ears, both say that the Lahr biography portrayed Halliwell as being loathed by all, but that simply was not true.

Prick Up Your Ears does well in the details, especially when it comes to the collage that Halliwell covers their tiny apartment walls with, but the film also tends to skim the surface of lives that were fascinating and complicated. It also avoids the use of any of Orton’s works, so much so that one can’t help but assume by the middle of the film that the Orton estate must have refused to license works to the film, hindering its production. Whether that’s true or not is unclear; what is clear is that the script relies on some well-placed barbs and one-liners to convey Orton’s wit, but often does this at the expense of context.

Ryan Gilbey, on the film’s 20th anniversary theatrical re-release, noted that the flatness and shallowness of the production helped mitigate the “rose-tinted hindsight” that sentimentality and nostalgia would have brought to the proceedings. He’s right, to a point, and the article is well worth the read, thanks to the timing: Prick Up Your Ears was made 20 years after Orton’s death, and Gibney’s article was written 20 years after Prick Up Your Ears, and important comparisons between the decades are made.

It’s those comparisons that are essential to telling the story of the audaciously out Orton and his mentally ill partner, however. Without understanding the society they lived in, it’s impossible to comprehend the full impact of their actions. Likely, in 1987, no one needed to be reminded that cottaging was salacious and illegal and considered highly immoral, and perhaps the film was not so much negligent in setting up the background as it is guilty of simply not wearing well.

Biographer and drama critic John Lahr wrote the book on which this movie is based, and has ended up as a character in the film, too, portrayed in the film by Wallace Shawn, who (probably not coincidentally) had the real-life Peggy Ramsay as his agent for many years. Though generally praised for her performance, Vanessa Redgrave approaches Ramsay with what looks like a Vera Charles impersonation: the archetypal composed, stylish, clever, cold and clipped woman of a certain age, who for some reason doesn’t recognize the hypocrisies of her words.

It’s hard to tell if this is characterization or a failure of the script, honestly, as the subplot about Lahr and his wife show. His wife Anthea, played as a silly, resentful, übermaus Hausfrau by Lindsay Duncan in a role that seems as though it were meant to insult the real-life Anthea Mander, is ignored both by Ramsay and Lahr, and this is meant to parallel the way Halliwell felt about Orton two decades prior. But this subplot just wanders off at some point, never to return, and a final summary of the parallel manifests as the strange sexist-homophobic idea that one man in a gay relationship must be the “wife.”

Still, for all its issues and despite being dated, Prick Up Your Ears features some very funny lines, fine performances and a handful of striking scenes that make the watch well worth your while.

Prick Up Your Ears has just been released by Olive Films on Blu-ray and DVD. The Blu-ray comes with chapter stops and the theatrical trailer. The picture quality is okay, though be prepared: this is a British film from 1987, and the film quality really shows it. It’s grainy throughout, with some scenes and shots far grainier than others, to the point that scenes can look sparkly or snowy, like TV stations just a little outside of your antenna range used to look.