Daisy Kenyon (Joan Crawford) is a successful commercial artist in love with the high-powered (and very married) attorney Dan O’Mara (Dana Andrews), the kind of smooth operator that charms everyone but his beleaguered wife (Ruth Warrick). At an uncertain point in their affair, Daisy meets the sensitive war veteran Peter Lapham (Henry Fonda), a widower who may be unstable but is also very kind. In an attempt to get away from her toxic relationship with Dan, Daisy marries Peter and they try to build a life together. Complications ensue — would there be a movie if they didn’t? Director Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon (1947) treats its titular character in a comparatively realistic, morally way, especially in its portrayal of a love triangle that goes completely and unsurprisingly wrong.

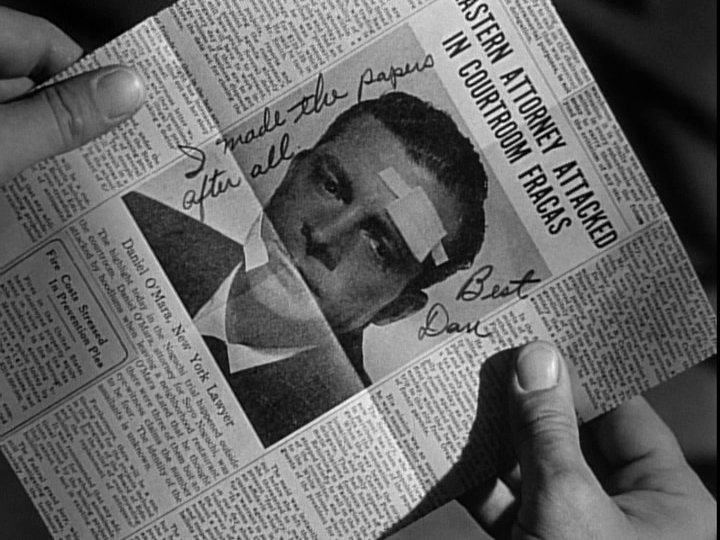

It’s fascinating to see so many critics and fans, both now and then, consider Dan to be the quintessential “great guy,” someone gregarious and successful and handsome and everything a woman could want. To me, Dan has always come across as a parody of the cinematic perfect man, a mash-up of an old pre-Code ruthless businessman with the current (for 1947) hard-boiled private dick. He shows his contempt for people by constantly calling them “honey bunch” or, for variety, “sugar plum,” which has lead many to consider Dan a hard-boiled character and the film, by extension, a film noir, but I don’t think it is, not strictly anyway. Dan may fight for the rights of the disenfranchised, but he can’t be arsed to spend time with his kids, dislikes his wife, and is contemptuous of everyone, including his alleged true love Daisy. Every time he goes to Daisy’s studio, he turns off her music without asking; David Raskin’s score was as much part of Daisy’s character as Joan Crawford, and when Dan turns it off, it’s almost as though he’s ending Daisy herself. There were so many examples of Dan disregarding Daisy’s well-being and feelings that one is hardly surprised when he attempts to rape her.

I make him sound like a monster, but that’s only because he is. A recent biography contends that Dana Andrews’ third film with Preminger, Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), was the cinematic version of watching Andrews’ “polished persona” disintegrate. It’s a good argument, and I think can be taken further to include this, Andrews’ second film with Preminger, showing a “polished” man with such rough edges you can’t get near him without slicing open a vein. Yet, in true 1940s melodrama form, he comes across as reasonably likable. At the end of the film, Daisy very rightly and reasonably tells him that most of his actions were simply him trying to run away from his own responsibilities, and I almost cheered out loud because that’s the kind of logic conspicuously absent from most melodramas.

It’s not a surprise in Daisy Kenyon, though, which works overtime to deconstruct and critique women’s films. Crawford gets this, and in her performance you sense she really enjoys being able to tell these men the kind of hard truths they really need to hear. Kenyon especially borrows from older pre-Codes, the kind of films Crawford, as I’ve mentioned before, was never in; she spent her time in light romances. But all the pre-Code melodrama is here: the successful and handsome businessman who has an undeserving shrew wife and a beautiful girlfriend on the side who is both sympathetic and the star of the film. The only difference is that Daisy’s choice of the “right” guy, a widowed and sensitive veteran, would usually be the happy ending in those films. In Daisy Kenyon, it’s just the beginning.

Look closely at the room divider inside the doorway. The screen has a black line drawing of the right half a chair which perfectly lines up with the actual chair directly behind the screen. Later in the film when Daisy is making coffee, you can see the black line drawings on the right side of the screen match up with the cabinetry in her kitchen in the same manner. Neither the screen nor its design are ever directly referenced, but it’s a clear indicator of Daisy’s taste and artistic ability, and it’s fantastic. (This image taken from a previous DVD release of the film.)

Look closely at the room divider inside the doorway. The screen has a black line drawing of the right half a chair which perfectly lines up with the actual chair directly behind the screen. Later in the film when Daisy is making coffee, you can see the black line drawings on the right side of the screen match up with the cabinetry in her kitchen in the same manner. Neither the screen nor its design are ever directly referenced, but it’s a clear indicator of Daisy’s taste and artistic ability, and it’s fantastic. (This image taken from a previous DVD release of the film.)

Being a Preminger studio film, Daisy Kenyon of course includes some humanist moments that most other films in 1947 wouldn’t touch. There are all sorts of issues unflinchingly addressed such as child abuse, extramarital affairs, PTSD, rape, and the illegal discrimination against Japanese Americans during and after WWII, a topic which, as I write this here in November of 2016, has sadly come back into the news, thanks to a president who is supported by the KKK and folks who believe the internment of Japanese Americans in WWII to be “precedent” for similar policies today. Joseph Breen, a constant thorn in Preminger’s side, refused to allow a scene showing Dan actually defending Noguchi, the Japanese man whose property had been stolen while he was in a West Coast internment camp,[2] but the brief mention of it in 1947 must have been enough to set quite a few teeth on edge.

Joan is phenomenal in this film. This is a role that goes beyond the usual melodrama she was given, and she proves unquestionably that she could act. While fans of her melodramatic roles such as The Damned Don’t Cry and Harriet Craig will enjoy this, I think you’ll also notice a deliberate attempt by Preminger to step away from overt melodrama and delve into genuine adult emotion. I’m thinking specifically of the car crash scene, which is filmed from a distance in a scene of significant length with few (or no) cuts. It could have so easily become a Lana Turner Bad and the Beautiful moment full of screams and high camp, but thankfully it held restraint and, as such, was much more powerful.

In the special features on a previous DVD release, Robert Osborne says that Joan was way too old for the part. Bob’s said this kind of thing before and I usually disagree; in this case, I vehemently disagree. Daisy is an accomplished career woman who has been an illustrator for a long time and is quite set in her routine. She has control over her life, is a little hardened and now old enough to have shaken off the unrealistic romantic notions of youth. Joan, at most, is 41 playing someone who is about 37, which is hardly scandalous or unreasonable. The issue of the acceptability (or not) of Joan’s age resonates, I think, because the character of Daisy is a complex amalgam of many things, including of Joan Crawford herself. The contradiction of Daisy is that she has such strength of character, yet so easily crumbles into despondency, indecision and drama. Are we seeing Joan’s own personality peek through, or are we seeing Joan in the strong moments and Daisy in the weak? Preminger likely wanted us to ask ourselves that very question, and that he delighted in knowing that we would never have an answer.

Kino Lorber has just released Daisy Kenyon on a spectacular Blu-ray packed with special features: audio commentary by Foster Hirsch, a documentary on Otto Preminger, a featurette of the making of Daisy Kenyon, images and trailers. I apologize for not being able to get any screen shots of the Blu, but you can see some at Brian Orndorf’s review at Blu-ray.com. I have to admit that the soft lighting for Crawford didn’t look nearly as obvious on my watching as it does on their screencaps; I would say the quality of this Blu is on par with the quality of another Crawford film, Possessed (1947).

—

Sources:

[1] Hollywood Enigma: Dana Andrews by Carl Rollyson

[2] The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger by Chris Fujiwara

[3] Poster, studio portrait of Crawford, and color portrait of Crawford and Andrews courtesy Legendary Joan Crawford.

[4] Images of Crawford and Fonda, and of the newspaper clipping, are courtesy Northwest Chicago Film Society.