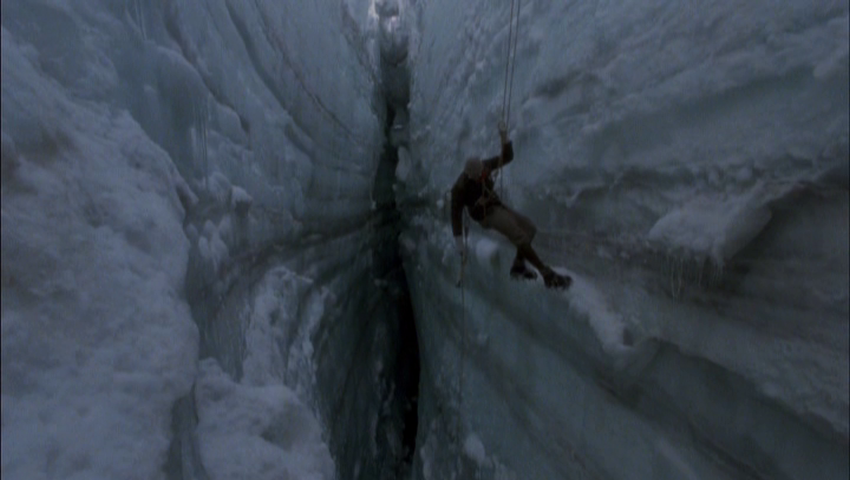

Dr. Douglas Meredith (Sean Connery) is on a climbing holiday in the Alps with his young wife Kate (Betsy Brantley). They’re happy and in love, but complications arise when Johann (Lambert Wilson), a handsome young climbing instructor, falls for Kate, and she begins to have feelings for him as well. Douglas senses the competition as well as the unstoppable passage of time, and in a bid to prove his masculinity and woo Kate back, suggests a treacherous climb with only Johann as his guide. An avalanche intervenes and only one man returns to Kate… but is it the man she wants?

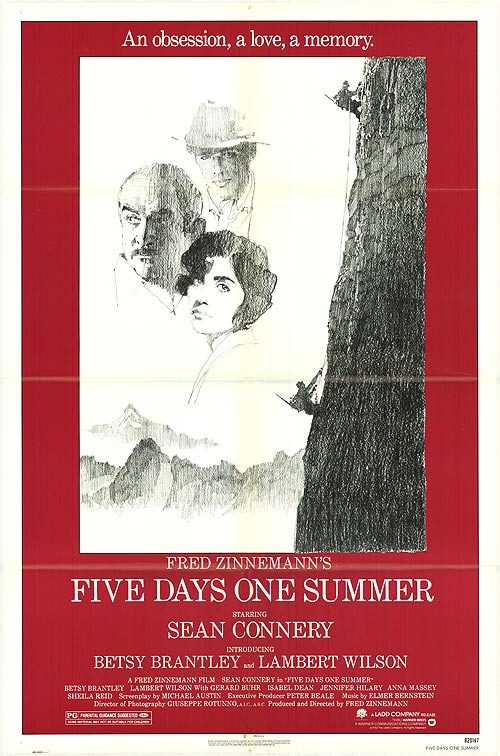

Five Days One Summer (1982), director Fred Zinneman’s last film, was a strange entry in a year that also saw films like Victor/Victoria, Porky’s, Silent Rage, Tron and Blade Runner. A quiet, deliberate affair, Five Days is impressive for its locations and styling, for the practical effects, and the commitment to creating art, if only for art’s own sake. Cinematographer Guiseppe Rotunno does a fantastic job during the climbing scenes, though elsewhere the quality of the film ranges from too dark to see to so soft you almost can’t make out anything tangible.

Janet Maslin called Sean Connery “dependably sturdy” in this film.

Still, the general consensus, both then and now, is that Zinneman didn’t pull off the intimacy necessary to make the film work. Most find the film far too slow — Variety called it “Five Summers One Day” — but I find the complaints about pacing to be overblown. It’s meant to be quiet and contemplative, and Zinneman achieves that most of the time, though admittedly there are several “you can’t eat popcorn to that” moments.

I never really found Zinneman an intimate director, anyway. He was always concerned with making sure every character’s thoughts were represented in the film in some way, so that there was never just one point of view in a film, but rather several stitched together like an unfinished quilt, with empty and unknowable spots in all the right palces. The weakness in that approach was that, if multiple characters were learning a truth or undergoing a transformation, Zinneman had trouble juggling these multiple concerns in one scene — the final scene with Donna Reed and Deborah Kerr in From Here to Eternity comes to mind — and that same problem pops up in Five Days, too, especially in scenes with Kate and Johann.

In a 1981 interview, Zinneman says repeatedly that the characters in Kay Boyle’s short story weren’t very interesting, but it was the ending that made the story special — he oddly kept referring to it as the “final solution” — but one wishes he had put more effort into making Kate and Douglas more cinematically interesting. They’re not so dull as to irritate, but they’re more sketches than humans; his decision to approach Five Days as “a sentimental sort of a thing” where a romantic little tale is all that’s needed is is obvious, but not wholly effective.

His commitment to updating the old-fashioned nature of the story is also obvious, and probably the most compelling part of the film. Five Days One Summer is reminiscent of movies in the early days of sound where the scenery and location were enough for audiences (or at least studios thought so) and a light plot was tacked on just to give the cameras an excuse to be there. It’s probably no coincidence that Zinneman considered making the film in black and white, though thankfully decided against that.

Still, there’s something unsettling, and deliberately so, about a film that on the surface seems like a light little travelogue, but underneath is really about a young woman posing as her own uncle’s wife. The cheery, colorful flashbacks to Kate as a girl of about 10, complete with sweeping and romantic music to show that she is already in love with her mother’s brother, a man of at least 50, are quietly disturbing, and retroactively inform prior “present day” scenes where others at the chalet are scandalized by the alleged Mrs. Meredith’s youth.

Brantley’s performance directly mimics the starlets of the 1930s and 1940s, though she is hardly made up in the glamorous way everyday, poor, downtrodden, or even injured characters were made up during the studio system days. But she has the mannerisms down pat, especially the pause and broad smile after we’re shown a particularly lovely bit of scenery, and the still-as-a-statue melancholy meant to evoke almost suicidal despair.

Warner Archive has recently released Five Days One Summer on a made-on-demand DVD, which comes with the film and the theatrical trailer.