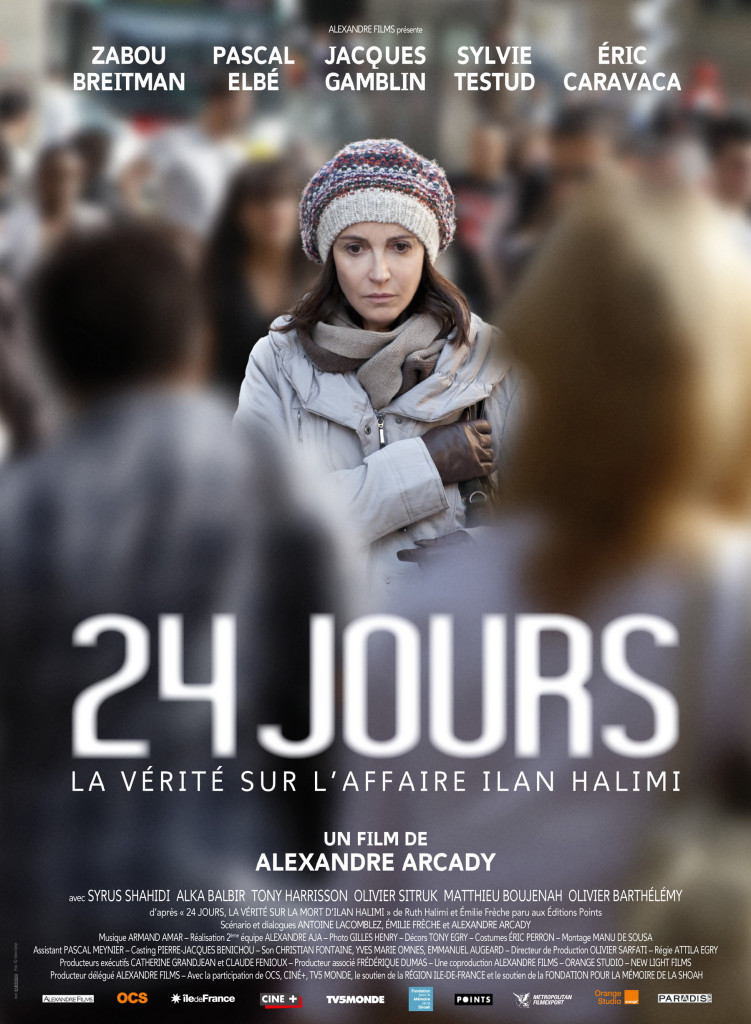

24 Days (24 jours)

★★★★✫

Director: Alexandre Arcady

Menemsha Films (Official Site)

110 Minutes

Release Date: April 24, 2015 (limited)

–

It’s Paris, 2006, and handsome young Ilan Halimi (Syrus Shahidi) has been kidnapped, his family tortured by angry phone calls demanding €450,000 for his release. If the Halimis were a rich family, this might make a kind of perverse sense, but Ilan’s parents Ruth (Zabou Breitman) and Didier (Pascal Elbé) have been divorced for 20 years, and both are of modest means. When the police become involved, they discover a large network of kidnappers who use attractive teen girls as bait, and who specifically target Jewish males. Yet the police refuse to consider this a hate crime, and their methods of dealing with an obviously unstable gang leader are questionable.

Based on a true story, 24 Days is a harrowing affair that unfolds slowly, often frustratingly so. Bookended by narration from the mother, who addresses the audience directly, 24 Days seems at first to approach the topic almost as a documentary, but soon turns into a taut, sleek police procedural. Alternating between scenes of the extended family at home and at the police department are shots of the kidnappers themselves, a large group of people whose motivations and rationalizations are unclear.

24 Days is a fine-looking film, its quieter moments full of striking symmetry, comforting angles and pleasant apartments in a warm, low light. In stark contrast are the scenes of the kidnapping and aftermath, though the reliance on fast hand-held camerawork and deep black tones tends to look cliched. Many scenes are also saturated in the exact same shade of blue that every film is saturated in nowadays, with civilians and gang members often in outfits so color-coordinated they look as though they’re wearing unforms.

The film does solid work in maintaining suspense, even for those familiar with the case, though some of the suspense comes from our natural curiosity to know more about the crime, and more about law enforcement’s reasoning was when they declared it had nothing to do with anti-Semitism. 24 Days wisely chooses not to provide answers, but at times the film’s attempted neutrality goes too far, leading to characters that are only lightly drawn and plot points that go nowhere. We know Ilan was cheating on his girlfriend, for example, and that the friend he used for an alibi lied to the police in the beginning. This implies that a “bros before hos” mentality potentially hindered the early hours of investigation, but once the lie is revealed, nothing more is ever said. We later see Ilan’s sister fielding a call from another woman Ilan had on the side, and though she silently ponders the situation, again, nothing comes of it.

Some of this vagueness is deliberate, of course. 24 Days purposely exploits stereotypes, relying on the audience’s tacit acceptance of helpless women, “butch” female cops and stoic patriarchs to make us complicit in the same kind of sociocultural attitudes that likely lead to this crime in the first place. Yet with 24 Days leaving so much unexamined, there are times when the film is guilty of perpetuating the same stereotypes it means to question. The most troubling moments come during scenes featuring Django (Tony Harrisson), a black man from Côte d’Ivoire. The police are casually racist and there is subtle yet highly effective commentary on racial profiling made in the film. At the same time, 24 Days indulges in some cheap and racist tricks of its own, such as the scary sound effect when his face is first revealed, plus a pervasive ethnocentrism that focuses on Django to the exclusion of everyone else.

Excellent performances, especially by Breitman and Alka Balbir, playing Ilan’s mother and sister, respectively, add much-needed substance to a film that, for nearly a third of its runtime, becomes a series of repetitive scenes hinging on whether someone will answer a phone or not. The light touch 24 Days displays in its social commentary is nearly perfect, however; it refuses to definitively come down on either side of the argument, instead walking a fine line by describing not an anti-Semitic act, but a crime that had the character of an anti-Semitic act. It doesn’t condescend to the viewer, but it also never lets them forget that those involved in this tragedy were not simply characters in a story, but human beings.