This is the SBBN entry for Krell Laboratories’ and Bemused and Nonplussed’s John Ford Blogathon, which ran from July 6, 2014 to July 13, 2014. Eagle-eyed readers will notice this post failed to make the deadline by a few minutes, and for that, SBBN apologizes, but wishes to state for the record that once the prednisone kicked in, all bets were off. Please take a moment to read the terrific entries for this blogathon. Thanks to Krell Laboratories and Bemused and Nonplussed for hosting this fabulous ‘thon!

This is the SBBN entry for Krell Laboratories’ and Bemused and Nonplussed’s John Ford Blogathon, which ran from July 6, 2014 to July 13, 2014. Eagle-eyed readers will notice this post failed to make the deadline by a few minutes, and for that, SBBN apologizes, but wishes to state for the record that once the prednisone kicked in, all bets were off. Please take a moment to read the terrific entries for this blogathon. Thanks to Krell Laboratories and Bemused and Nonplussed for hosting this fabulous ‘thon!

–

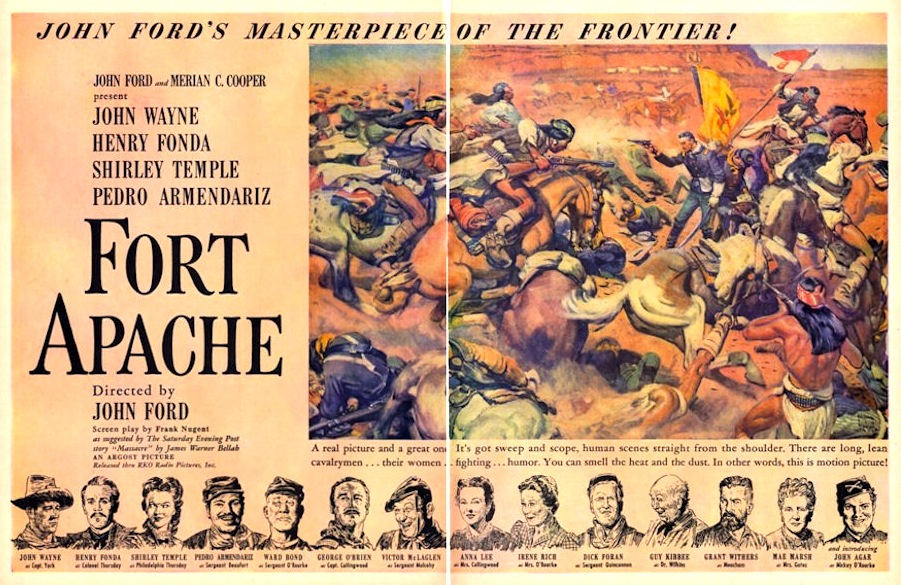

Fort Apache was the first film of what would become known as director John Ford’s “Cavalry Trilogy.” Though Ford worked within the same historical period in other films, too, these three movies — Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande (1950) — were loosely tied together thanks not only their shared historical setting, but because they were released consecutively and featured period-appropriate music used as strong thematic elements, the role of Irish immigrants in the United States’ brutal expansion through Native lands, and a subversive, critical approach to the policies of the United States government.

Photo courtesy 50 Westerns From the 50s.

Photo courtesy 50 Westerns From the 50s.

Lieutenant Colonel Owen Thursday (Henry Fonda) has been transferred to a remote outpost in Arizona known as Fort Apache. Certain he’s being pushed aside by the powers that be and more than a touch irritated at the fort’s isolation and, in his mind, insignificance, Thursday is beside himself with the indignity of it all. When he arrives, his curt demands and orders are taken by his men, but not without occasional comment. The most outspoken is Captain Kirby York (John Wayne), an expert in Apache relations and a valuable soldier, whose acquiescence to orders somehow merges seamlessly with his insistence on informing Thursday of his many mistakes. Thursday, seeking to make a name for himself, foolishly underestimates a nearby group of Apache who refuse to live on a government-designated reservation. Thursday is based heavily on Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, and seems driven to take the film to a finale we can see coming from just under 12 parsecs away; the meat of the movie, however, is in its many tangents, standalone comedic scenes and moments of sublime humanity.

Based on the short story “Massacre” by James Warner Bellah, Fort Apache’s screenplay was written by New York Times film critic Frank S. Nugent. He had reportedly written over 1,000 reviews for The Times prior to leaving for Hollywood; in many of those reviews, he praised John Ford — he apotheosizes him, really — and a particularly exuberant review of The Grapes of Wrath took him to Hollywood. Fort Apache was his first screenplay sold, and he would go on to write She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, The Quiet Man, Mister Roberts, The Searchers, and many others.

John Ford loved his landscapes. As American soldiers and their families travel about, the lands are flat, save for the gargantuan, distinctive outcrops. Frequently, these mostly-white Americans are dwarfed by their natural surroundings, little ants scurrying about a table they’re not supposed to be on. The Native peoples, on the other hand, are seen mostly in craggier, rougher terrain. They’re part of the landscape. They understand it, they use it wisely; they belong. Even in large group scenes, such as just prior to an ambush, we’re much closer to the Apache than the U.S. soldiers, enough so that we can make out their faces and their expressions as they hide behind rock formations.

For all the talk of Ford’s The Searchers (1956) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964) being in part an apology for prior racism and other troubling aspects of his films, Fort Apache, taken individually, is remarkably progressive and nuanced in its treatment of Native Americans. A scene is included to explain why York and Sergeant Beaufort are speaking Spanish when negotiating with Cochise, a remarkable thing, considering how often films were happy to use Spanish as a Native language out of laziness and, very probably, ignorance. It wasn’t perfect, however, as Cochise was played by a Mexican actor, not a Native, and it’s likely few or no actual Apache were cast as Apache extras.

Yet the dehumanization of the Apache is a primary theme throughout the film. York rails with great conviction against an organization he calls the Indian Range — probably referring to the Indian Office, run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, who sent out so-called Indian Agents to sell goods to Native tribes and enforce a series of racist laws. The Agents were widely regarded as corrupt back in the 1870s, when Fort Apache takes place, and the Indian Agent in charge of the local store, Silas Meacham (Grant Withers), calls the Apache “children” and provides them with sub-par alcohol and trinkets, but no meat or useful items. He so offends York with his entire manner that he gets roughed up a little, and justifiably. What York says right there in 1948 is something that would be controversial today. We’re perpetually doomed to repeat the past, and our memories are short; Ford only barely got away with such a critical look at a U.S. government institution in 1948, just 70 years after Little Bighorn. Today, almost another seven decades later, it’s equivocal whether many people are even aware of the historical atrocities of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. It’s presented in Fort Apache as simple fact, though, and perhaps it’s facts like those that lead to the rather ambiguous ending, one that’s half flag-wavin’ patriotism, half deconstruction of racist American mythology.

Fort Apache exists in that all-too-short sweet spot in American cinematic history, at a point when John Wayne could truly act but had not yet become a caricature, where a movie could still be critical of the government and not be accused by HUAC (or the capitulating studio heads) of being pro-Soviet propaganda. In truth, 1948 was rather late for a film of this type, and Fort Apache must have gotten away with more by limiting its scope to an entirely internal political situation; though the film’s themes are easy to apply to U.S. foreign policy, because it very literally concerns only Americans, both indigenous and immigrant, it got away with a critical analysis of government policy that it never could have just a few months later. Henry Fonda would be graylisted after this film by studios wishing to disassociate themselves from actors with left-leaning politics, lest HUAC accuse the studio of being Communist sympathizers.

Beyond Wayne, there are uniformly wonderful performances from nearly everyone in the film. Guy Kibbee has a small, almost cameo role which shows the man could truly act. He’s almost unrecognizable in his first scenes, stepping just far enough away from his long-standing comedic persona to achieve a warmth and depth that he rarely does elsewhere. Fonda shows his usual preternatural ability to be an unrepentant asshole, cruel and selfish and barely human. Supporting roles by Pedro Armendariz, George O’Brien, Miguel Inclan and Anna Lee round out a fine cast.

Shirley Temple, playing a young woman with the unlikely name of Philadelphia Thursday, was 19 during shooting, and though Phil’s age is never said outright, she is noted to be two years too young to marry without parental permission, making her about 16 years old. The daughter of Lieutenant Colonel Thursday, a widower who relies on his daughter to do the household and social work his wife would have done had she survived, Phil has very little to do in the film other than react to the actions of the men around her. Like all of the women in Fort Apache, she keeps house, she dances, she attracts the eye of the men around her. She also kisses the young Lieutenant Rourke, played by John Agar in his first film, so wet behind the ears you wonder if perhaps he isn’t just a sentient trout in a sharp uniform. Compliant and dull, the young Philadelphia Thursday floats through the film like a nonentity, existing only for the romantic subplot, one of about a dozen tangents that Ford indulges in.

These little subplots, somehow, almost entirely subvert the main thrust of the film, as though Ford couldn’t bring himself to fully engage with the expansionist philosophy that lead up to the real-life battle at Little Bighorn on which Fort Apache is based. Instead, we see the antics of the Irish immigrant soldiers, the young romance, the never-fully-explained history between Thursday and Captain Collingwood. It’s anything to take the focus away from the primary war themes, either by skipping from one tangent to the next, or becoming overwrought and heavy-handed when returning to the topic of conflict. Yet Ford appears to have been having fun at times, goofing around, indulging in a little Sennett-style slapstick and even a naughty visual pun or two.

Somewhere, Alfred Hitchcock nods in approval.

Somewhere, Alfred Hitchcock nods in approval.

It’s Ford’s artistic restlessness that gives real substance to this film, because it’s what makes the film human. It may look haphazard and disorganized on the surface, but every time Fort Apache veers off into some little narrative cul-de-sac about furnishings or bootleg liquor, we’re learning about the lives of characters that other films wouldn’t even bother to name, characters who are lost, mostly off screen, in the inevitable massacre.

As Katherine Kalanak notes in How the West Was Sung, the cynical ending is undermined by Ford’s choice to use the ultra patriotic “Battle Hymn of the Republic” in the soundtrack. Captain York’s conflict, shown in his downturned eyes and rote confirmation of all the lies the media are hungry to believe, is played almost as a necessary evil to achieve American dominance. These men won’t be forgotten, York says, because they will be replaced by new men, men that a 1948 audience would all too keenly remember were lost in the most recent world war, and the previous world war, and so on.

Cutting-edge for the time, infrared photography rendered the sky dark with the clouds popping off the screen. In this shot, the reflection of the clouds, either coincidentally or ironically, form what looks like warpaint on York’s face. No warpaint is ever scene on the Apache in the film.

Cutting-edge for the time, infrared photography rendered the sky dark with the clouds popping off the screen. In this shot, the reflection of the clouds, either coincidentally or ironically, form what looks like warpaint on York’s face. No warpaint is ever scene on the Apache in the film.

If York’s earlier order to a fleeing Lieutenant Rourke that he marry Philadelphia sounded like the plea of a man afraid no one would live to propagate the species, his ultra patriotic, pro-military routine at the end brings that thought full circle. The young Rourke progeny is brought forth as a tangible, frightening example of the babies who will become men who will become cannon fodder rotting on the fields when the wrong man is once again put in charge. Perhaps the use of “Battle Hymn” was meant ironically, or perhaps only to soften the blow of this harsh observation.

Ford, it should be mentioned, cheerfully used silent film and early talkie cinematic techniques for Fort Apache (and other films even later in his career), thus it’s quite possible that he intended this ending to work in much the same way as similar “all’s well” endings in pre-Codes: you have your fun for an hour or so, then in the last five minutes, all the morality chickens come home to roost and lay eggs on everyone’s heads, allowing censors and the more delicate among us to forget the subversive themes we had been enjoying for most of the film. More specifically, there is an undeniable link between Fort Apache and D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, in its aesthetic and its tone as well as its cinematography and overarching themes.

But Fort Apache is conflicted. It doesn’t want to be racist, but it is. It’s political, but also neutral. It’s patriotic, but also questions the wisdom of a government run by extraordinarily fallible men. There are no real answers; hell, there are almost no real questions, either through Ford’s belief that questions were unnecessary, or perhaps his fear of uncovering the answers. Fort Apache, more than almost any other of Ford’s films, demands to be taken on its own terms. It may be a direct descendant of some rather troubling films, but it refuses to pay for the sins of its cinematic fathers.

Fonda shows his usual preternatural ability to be an unrepentant asshole, cruel and selfish and barely human

Someone once asked Peter Fonda what his father was really like, and Pete asked the questioner if he’d ever seen Fort Apache. When the man replied that he had, Fonda cracked: “That’s what my father was like.”

I like all three films of the “Cavalry Trilogy,” but Fort Apache is my favorite of the bunch…primarily due to its slightly subversive content, which you outline so brilliantly here. Outstanding piece, BBFF.

Thanks Iv!

I’m so glad you brought Peter Fonda’s comment up — I’d heard that anecdote before, but had forgotten all about it. Ouch. I wonder how much of a crack that really was? Both Peter and Jane had (what I will politely call) an interesting relationship with their father. Reminds me at times of the Crosby family.

I enjoyed this a hell of a lot more than Yellow Ribbon. For the life of me, I can’t figure out why Ford fluctuates the way he does when it comes to sociocultural issues and politics. An interesting guy, but frustrating.

I caught up with Fort Apache last year and was blown away by the final act and Fonda’s performance. I agree with your points that the subplots slow down the film and nearly upend the message, though they also allow us to understand the characters and the community.

After seeing the way Native Americans were portrayed in this film, I was surprised that Ford seemed to take a step backwards with She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. I liked that film (especially Wayne’s performance) but am partial to Fort Apache because it has more to say about the government and our history.

Fonda was quite good in this. Every so often, he gives a performance that really impresses me. So many people like, say, 12 Angry Men, or Once Upon a Time in the West, and they’re not bad performances in the least. But Daisy Kenyon is really astonishing, as is Fort Apache, and even Warlock. All great performances you just never hear about as much as the others.

You’re right about Ford’s fluctuation, and it just drives me bonkers, really. One of these days I’m going to dig into some bios and see what others say could account for Ford’s artistic-moral fluidity.

The bio by Scott Eyman, “Print the Legend”, is really interesting. I’m not sure it explains that side of him that well, though. Ford is so full of contradictions. I read through it once and now just go back and read the sections on the films as I get through them. It’s pretty hefty for a single read at over 600 pages.

Excellent, fascinating review and an interesting perspective.

I’ve always felt that the “conflicted” aspects of Fort Apache that you mention — political/neutral, patriotic/questioning the government, etc. — were Ford’s way of getting past the censors in a particularly volatile political era in U.S. history. He clearly shows us the shortcomings of the government in its fractured policy towards Native Americans, and that, like Thursday, Custer’s hubris, his military (and political) aspirations, and poor judgement were irresponsible and wrong. Wayne’s answers to the journalists at the end serve two purposes: to confound the Hayes Office into thinking FA was a patriotic film, and to show the stifling nature of military protocol in that York could say nothing critical about Thursday’s actions leading up to the massacre, or the government’s part in it (allowing corrupt Indian agents to exacerbate Native Americans’ plight, and forcing them to live on reservations under unlivable conditions) without going before a court martial and perhaps being shot for treason. He speaks with little or no emotion, “by the book,” which implies, to me anyway, that he’s unwillingly following protocol by rote. What’s fascinating is that, to this day, many viewers and even some critics take York’s words at face value and assume the film is a “flag waver.”

Interestingly, Ford wanted to end They Were Expendable (1945) on more of a down note, with the defeat/evacuation of U.S. forces from the Philippines, but MGM suits tacked on a coda with an upbeat quote from General Douglas MacArthur with “Battle Hymn of the Republic” playing on the soundtrack. Perhaps Ford learned from this and beat Republic Pictures to the punch so that Fort Apache could be released without any post production fuss. Also, Ma Joad’s inspirational speech at the end of The Grapes of Wrath was tacked on by producer Darryl F. Zanuck; Ford had ended it with Henry Fonda leaving his mother and family as he escapes of the hill, a wanted man.

Whatever the case, FA never ceases to fascinate, or to stir up controversy.

Here’s an insightful review of FA by Dave Kehr of the NY Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/25/movies/homevideo/john-fords-fort-apache-on-blu-ray-from-warner-home-video.html?_r=3&

I definitely think some of the conflict has to have been because of studio (and HUAC and censorship) issues, but Ford’s persona never seemed to show him as the kind of person who caved in to those kinds of demands, so it’s really peculiar for him to get away with so much in films like Fort Apache, then fall backward (as it were) with Yellow Ribbon.

So glad you brought up that story about They Were Expendable; I had heard it and didn’t recall it when writing this, but you’re right, it’s from a few years prior to FA, and could have had quite an influence on his decision.

Kehr’s piece is really good. I’m lukewarm on Kehr overall — he seems like the kind of guy I’d want to talk films with for ages, and of course read the blog of, but sometimes his pro articles can be a little cranky in that way that film critics are “supposed” to be. I blame John Simon.

But it’s good policy to just blame John Simon for everything, all the time, so.

I don’t dismiss Philadelphia from the equation of the fine elements of the movie. Her character, so outgoing and uncalculating, is such a contrast to her father. She makes friends at the Fort while he alienates everyone.

Absolutely, but everything she does is in reaction to/relation to the men around her. She’s never given anything of her own. Mary O’Rourke (a really terrific Irene Rich) gets a lot more substance to her character. Even Emily Collingwood does, too. With apologies to Shirley Temple fans, some of the problem is that she does not have a lot of depth in her usual performances, and up against Agar in one of the most blatant “god bless him, he’s tryin'” perfs I’ve ever seen, she really didn’t stand a chance.

I find “Fort Apache” fascinating and I can’t not watch it when it’s on TCM. Fonda’s character is as astoundingly “misguided”, to put it mildly.

Now that I’ve read your post, I’m wondering why I don’t actually own this movie. I’m off to do some shopping at Amazon.

Ahem…why not check the eBay auctions of cineaste1? (Shameless…aren’t I?)

Heh. When opportunity knocks…