Hilary Dow (Susannah York) has left her husband Douglas (Michael Craig) and returned to her childhood home, a large estate owned by her brother Sir Charles Henry Arbuthnot Pinkerton Ferguson (Peter O’Toole), known as “Pink.” As Brotherly Love (1970) opens, Hilary runs into her estranged husband at a livestock sale. It’s apparent she’s still attracted to him, though as the film continues, one has to wonder why. He’s dull and staid and full of that contemptuous violence men, especially in British films of this era, had for their wives. She buys a beautiful white gown for the Young Conservatives’ country dance later that night, knowing Douglas will be there, and resolves not to tell her excitable brother Pink.

Pink, of course, finds out, and when he does, we realize he’s not so much eccentric and excitable but fully in love with his own sister, and that these siblings share a dysfunctional and unconventional past. Still, when Pink says he’s always been fond of Douglas, you believe him, and he seems less upset at Hilary’s possible reconciliation than he is at her inevitable departure from the family farm.

In films from this era, the use of sibling incest as a plot point tends to be of the generic (and literary) rejection-of-the-family type, which is very true of Brotherly Love. Written in a theatrical and frequently metaphorical style by James Kennaway, the film is based on Kennaway’s novel Household Ghosts, which was then turned into a stage play in 1967, and finally a film in 1970. Kennaway wouldn’t live to see the film’s release, however, as he died of a heart attack in 1968.

Brian Blessed appears in a small (and muscular) role as Jack “Jock the Cock” Baird.

In some iterations, one wonders if the themes of sibling incest aren’t being presented as a benign coping mechanism for major childhood trauma. In Brotherly Love, Pink’s very survival depends on his sister’s love, and there’s enough ambiguity about to imply that a platonic love would suffice; it’s protection he wants, not physicality. Further to that point, Hilary’s resistance to staying with Pink seems as much about her own physical needs as it does about resisting Pink’s unhealthy attentions.

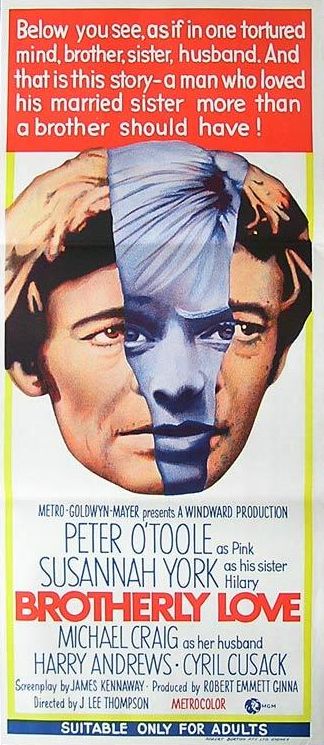

Directed by J. Lee Thompson, Brotherly Love looks and feels like a particularly saucy television adaptation. After the one-two punch of Guns of the Navarone and Cape Fear in the early 60s, Thompson was not known for particularly good films; Firewalker was one of his last. Thompson had been involved in the stage production of the play in 1967 and had always imagined a film adaptation, though Kennaway’s death understandably delayed things. The film was originally meant to be released as Country Dance (and one can still find quite a bit of publicity about it under that name), then briefly was known as The Same Skin, before the very literal Brotherly Love was chosen.

The dark circles under O’Toole’s eyes unintentionally make him look like he has eyes that are such a bright blue they can be seen from a distance.

Much of the comedy in the film comes from Pink’s strange behavior and the fact that it’s shrugged off by those around him who are apparently quite used to members of the aristocracy being a bit off. He’s a baronet, the recipient of a hereditary title that means he is technically not a nobleman, but still above a knight in the royal hierarchy. It’s the perfect title for a family destined to die out, one that seems more a last vestige of landed gentry than actual aristocracy… but landed gentry doesn’t harbor a nasty reputation for incest, does it, Mr. Poe?

Brotherly Love has been saddled with the label “tragicomedy” for decades, though there is very little outright comedy here, just wry observations and O’Toole waving his arms about more than usual. Speaking of Poe, this is a film that could have used a bit of the wink-and-nod styling of a Roger Corman or a Vincent Price, and in fact the original novel is far more successful at that tone than the film is. Essentially, York and O’Toole both give fine performances while both seemingly failing to understand the humor in all of this. Though the screenplay was written by Kennaway, it feels like an inferior adaptation, and O’Toole’s role feels like a rehearsal for The Ruling Class (1972).

Vincent Canby noted that one never sees the outside of the Ferguson estate, which is very true, but what he doesn’t note is that it’s done so deliberately that it becomes positively infuriating. Every other exterior is shown in an establishing shot, and multiple times — the film is rubbing your face in the fact that you can’t piece together the geography of the Ferguson estate. It wants you to imagine that the physical location of all this dysfunction is too complex or intricate to comprehend, but it’s not; they’re just withholding basic information from you like in a cheap mystery novel.

As Canby says, the film is ridiculously demure, surely to avoid controversy given the subject matter. There’s one particular moment when Hillary, having just enjoyed a night with her husband, rolls over nude in bed. The film deploys some spectacular staging to cover anything even remotely naughty on York’s body. It’s a marvel of blocking and lighting, especially for a film where you could get very blasted if you were playing the Spot The Boom Shadow Drinking Game, but one wonders what the practical point of it all was. If they really wanted to avoid controversy, surely they wouldn’t have used the bitchy “Not all love is beautiful” tagline, which adds a layer of conservative politics to the publicity that the script pointedly contradicted.

Brotherly Love earned mixed but mostly positive reviews on release and a spot at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1970, enjoyed a very short run in theaters in 1971, then disappeared. Warner Archive’s MOD DVD is (I believe) the first time the film has been available on home video. The print is quite dark and scratchy but nothing you won’t expect from an early 1970s movie from the U.K., though the aspect ratio seems a little off. The DVD comes with the original trailer.

—

Additional Sources:

Variety review of Country Dance (1970)

J. Lee Thompson by Steve Chibnall, pp 320 – 331.