September 23, 2014: It appears Universal already demolished Stage 28. A photo of the pile of rubble that was left by the afternoon of the 22nd, courtesy @insideuniversal:

CoasterMatt on Flickr rode past the building being torn down during a Universal tour on September 18th — you can see them here — but the building itself, as of the afternoon of September 22, 2014, is gone.

—

This is the SBBN entry for the Journeys in Classic Films Universal Backlot Blogathon, running from September 14 through 16. Please check out all the fine entries!

***

The oldest extant movie set is, somewhat surprisingly, one still in use today. Stage 28, located on the Universal Studios backlot and built for the Lon Chaney classic The Phantom of the Opera, was completed in 1925. The enormous set sits atop an iron skeleton for support and is five storeys tall; it has been used for dozens of films over the decades, and though the iconic balconies from the 1925 silent Phantom are somewhat hidden, they remain intact.

In 1922, Gaston Leroux, author of the 1909 novel The Phantom of the Opera, met the vacationing president of Universal Pictures, Carl Laemmle. Laemmle had been captivated by the beauty and scope of the Opéra de Paris earlier in his vacation, and Leroux, sensing an opportunity, offered Laemmle a copy of his novel. According to legend, Laemmle stayed up that night reading the book, and by the time dawn broke was resolved to turn Phantom of the Opera into a Universal film. Less than two years later, rights had been acquired and production began.

Production on the film was, as they say, troubled. Laemmle had personally chosen Rupert Julian to direct, a man who had made a career for himself in the mid to late 1910s both acting in and directing programmers. But in 1923, he had scored a significant hit with Merry-Go-Round after replacing the fired Erich von Stroheim, and his success ensured he would direct what Laemmle had hoped to be Universal’s biggest spectacle to date. Julian, however, had an uneven reputation. His films were not generally critically praised, and many in the industry found him difficult to work with because of his brusque attitude and perfectionism, though silent actress Ruth Clifford remembered him as “lovely” and “gentle.”

Lon Chaney, star of Universal’s Phantom, surely disagreed. Many sources state he had been loaned out from MGM by Irving Thalberg, though Chaney scholar and make-up artist Michael Blake reveals in his bio of Chaney that the actor was most likely a free agent for the months he worked on Phantom. And during those months, Chaney had definite ideas of how he wanted to give life to the Phantom, his own theory of the character being a much more subtle performance than Julian wanted. The resultant clash was so extreme that neither spoke to each other and Chaney demanded to direct himself in all his scenes. According to Michael Blake, Universal cameraman Charles Van Enger had to act as a go-between:

“Julian would explain to me what he wanted Lon to do, and then I’d go over to Lon and tell him what Julian had said. Then Lon would say to tell him to ‘go to hell.'”

There are many different film versions of the Chaney Phantom of the Opera, and have been from almost the beginning; those hoping for an in-depth and accurate detailing need to look elsewhere, as the best I can give you is a summary based on several contradicting sources.

The first cut of the film with Julian at the helm was previewed in Los Angeles in early 1925, but both the audience and Carl Laemmle were unimpressed. Laemmle hired Edward Sedgwick to film a new ending, something more exciting than the original ending of the Phantom being found dead at his organ.

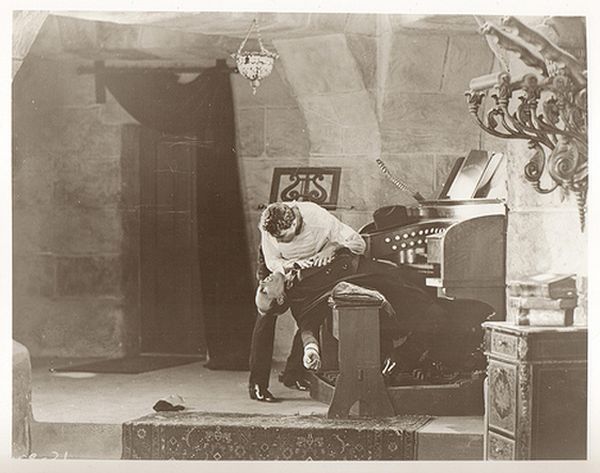

Promotional still of the original ending to Phantom, an ending shown only once at a January, 1925 premiere.

Promotional still of the original ending to Phantom, an ending shown only once at a January, 1925 premiere.

There were possibly other scenes filmed by Sedgwick, though they were not included when this second version was shown in San Francisco three months after the first premier; sources vary as to whether these new Sedgwick-directed scenes ever existed. What is known is that this second version was never released, either, and Sedgwick filmed even more scenes, adding a subplot with comedy great Chester Conklin and revamping the title cards.

Whether the comedic version was previewed, I cannot tell you, though even if it was, it was discarded and never officially released. A fourth version was created with the Chester Conklin scenes removed and some of the previously-cut dramatic scenes added back in, though some sources claim approximately 35 minutes from the original Rupert Julian cut were missing and never found. Some two-strip Technicolor scenes were re-shot, though at the same time the Technicolor scenes featuring the ballerinas were removed and lost forever. With a few more edits and new title cards to explain the now-choppy editing, this version was released in theaters in September, 1925, and is the silent version we know today.

In late 1929, a talkie version was made. Some scenes were re-shot and Virginia Pearson, who played Carlotta in the 1925 silent, was essentially demoted to the role of Carlotta’s mother. Mary Fabian, 15 years Pearson’s junior, played the new Carlotta. Other actors revisited their original roles with the exception of Chaney, who was at MGM by 1929 and, per contract, could not have his voice dubbed in. A third person narrator was used for all the Phantom’s scenes, and advertising was careful to mention Chaney’s voice was not in the talkie remake.

This talkie version was released in early 1930, and the film is lost. The sound discs exist, however, and recreations of the talkie version have been released on DVD. Of the two main prints of the film available today, there is the 1925 silent theatrical release, which is only available in a lesser-quality print, and a later international version from 1929, which is a re-edit of the 1925 version. It is also silent but substantially different than the original, and exists in a much nicer print.

For a fuller run-down of the differences between the 1925 and 1929 versions, start here at Rathcoombe Manor, as well as the left sidebar review at Silent Era here.

Promotional still from 1925. The balcony walls are almost all that remains of this massive set.

Promotional still from 1925. The balcony walls are almost all that remains of this massive set.

It’s true that there were a lot of edits and premieres before the film was released to the public, but Laemmle had reason to be picky. Not only did he want to create a massive spectacle, a film on an epic scale, but he also wanted a huge blockbuster hit. To that end, and with the memory of 1923’s Hunchback of Notre Dame‘s great success fresh in his mind, there was never any question that the sets for Phantom would be extravagant and well-publicized.

French film designer Ben Carré was consulted before production began, the idea being to have Carré’s designs in hand first and tailor the film to fit his set conceptions. Carré was chosen specifically because of his detailed knowledge of the Opéra de Paris, and he later claimed that, while the Opéra was certainly the inspiration for his designs, he often let his imagination go wild, delving into a Freudian style of imagery.

Two backstage scenes from the 1925 version of Phantom. The use of props from prior operas lends an otherworldly feel to the settings. And is that a statue pilfered from the old Intolerance set?

Two backstage scenes from the 1925 version of Phantom. The use of props from prior operas lends an otherworldly feel to the settings. And is that a statue pilfered from the old Intolerance set?

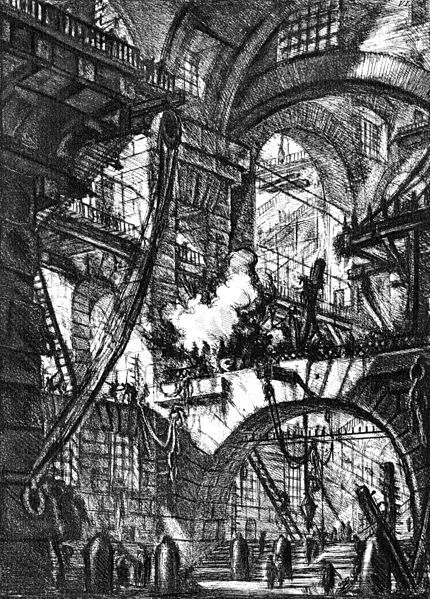

The result is that the architecture of the well-known staircase, stage, balconies, and orchestra pit of the Opéra were near-faithful reproductions — Universal claimed the opera house was made per the actual Charles Garnier plans for the real Opéra de Paris — while backstage areas were more fanciful. As one descends below the surface of the Phantom world, the secret lair of underground caverns and caves and lakes held no basis in reality at all; they were fantastic, implausible and surreal. The Imaginary Prisons series of prints by Giovani Battista Piranesi were said to have had the most influence on Carré’s subterranean designs.

Promotional still featuring Chaney and Mary Philbin in the flooded underground lair.

Promotional still featuring Chaney and Mary Philbin in the flooded underground lair.

Piranesi’s “Imaginary Prisons” number 6 (of 16)

Piranesi’s “Imaginary Prisons” number 6 (of 16)

Carré would ultimately be uncredited on Phantom, art director Charles Hall taking over during production and implementing the designs Carré had specified, but not without adding his own touches. Hall was the sadly underappreciated designer of almost all Universal’s early 1930s horror films, the visionary behind the iconic Universal Horror look.

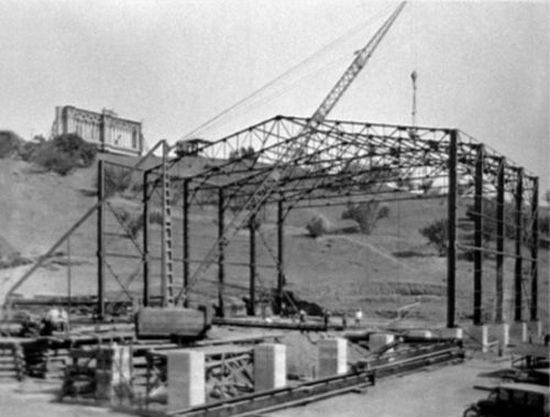

To create the life-size replica of the Opera House, Hall began construction on what is now known as Stage 28. Also constructed elsewhere on the Universal backlot were seven blocks of Parisian streets, and actual excavation for underground scenes was done in an area dubbed “Mount Laemmle.” The opera house, built five storeys high just as the original in Paris, sat on an iron “skeleton” used as the supporting structure for the set. The weight of not only the enormous opera house but hundreds of actors and crew and their equipment dictated a strong building, and the iron supports achieved that strength; it was the first Hollywood set of this kind, but certainly not the last.

Some of the old Hunchback of Notre Dame set can be seen on the hill in the upper right.

Some of the old Hunchback of Notre Dame set can be seen on the hill in the upper right.

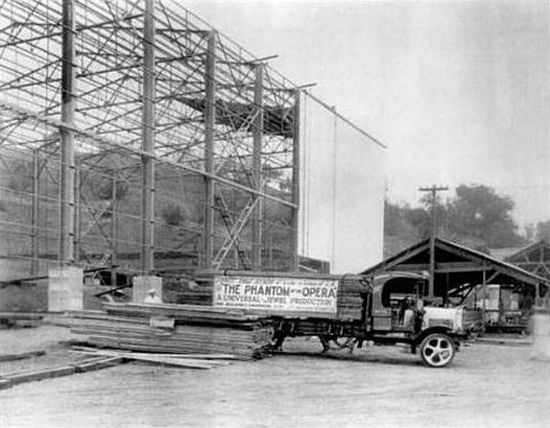

During production, the set was understandably called The Phantom Stage, and the name has stuck through the decades. The building measures 360 feet by 148 feet, and was constructed of a corrugated exterior, much of which still exists, and over 175,000 feet of lumber. Laemmle had banners advertising Phantom tacked onto the lumber trucks that drove through town, and plenty of publicity was garnered during the construction of the sets alone.

All interiors for Phantom were done on Stage 28, including the unmasking scene. Per some sources, only the water scenes in the long-forgotten “dungeons and torture chambers” under the Opera House were done on “Mount Laemmle,” while the shots in the cavernous rooms of the Phantom’s lair were interiors filmed on the soundstage. The scenes depicting the roof of the Opera House were also done on Stage 28.

When the film finally premiered in September, 1925, the sets were the unquestionable stars of the show. My beloved Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times called the film “a trifle weak” and noted the choppy editing from the multiple revisions, and saved his best praise for the art direction: “There is much to marvel at in the scenic effects,” he wrote, concluding that “the stage settings will appeal to everybody.”

Carl Sandberg’s first review of Phantom was nearly breathless in its excitement:

“Universal’s new production seeks for the chilling thrill, the scene that scares you, which is yet so new, so fascinating that your pleasure surpasses the scare. Its climax creeps upon you by compelling degrees; you shrink from it, yet you would not miss it.”

Not long after, Sandberg had a change of heart and deemed it merely “clever” though “worth the study of psychologists of public taste:”

“The aim is to send cold shivers registering down the spines of the members of the audience.

But these cold shivers must not be too cold, must not go so far as they did in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Nor as they did in Erich von Stroheim’s Greed … The latter two movies were not very strict box office successes; they were too fierce.

In making The Phantom of the Opera they figured on scaring the audience — but not too much, not too fierce.”

Since the release of The Phantom of the Opera, its sets have been used for dozens of films: The Mummy’s Curse (1944) uses some sets for exteriors of the monastery, as does the finale of 1943’s The Mad Ghoul. Other films using parts of the sets include Flesh and Fantasy, Pillow of Death, Thoroughly Modern Millie, The Sting, Scarface, Marnie, Torn Curtain and more. Stage 28 housed the large model planet of Metaluna during filming of This Island Earth; the model was the same one used for the Universal logo, slightly modified.

An interesting, if apparently untrue, tale was attached to the set after the 1935 horror classic The Raven was filmed there. Universal press released stories about the scene where Dr. Vollin (Bela Lugosi) shoots Bateman (Boris Karloff), a scene filmed on some of the Phantom sets. Universal claimed that actual bullets were used for the scene, requiring Karloff to wear special bullet-resistant (not bulletproof!) plating as a Universal firearms expert shot at him from off camera. The expert, according to the story, grazed Karloff and the bullet traveled past to the back wall of the set, chipping some of the plaster.

In 1965, Karloff was asked about the incident. After laughing for a bit, he said no, that if he had been shot — even grazed — he would remember it, and that he would never have allowed Universal to use live bullets on him for the scene anyway.

The 1943 remake of Phantom of the Opera won an Oscar for Art Direction-Interior Design, in part by using the original sets: “All it needed was repainting, new drapes, a new front curtain and a new backstage” said director Arthur Lubin in a later interview. The set was also soundproofed for this version. Nearly 15 years later, the sets were used for the Lon Chaney bio-pic Man of A Thousand Faces.

French singer and actress Gaby Deslys reportedly owned this wooden bed shaped like a swan, which was purchased by Universal’s prop department at an estate auction after her untimely death in 1920. Universal made sure everyone knew it, too. From Mordaunt Hall’s review: “You see the bed once owned by Gaby de Lys, which resembles a boat swung from three pillars; then there is a coffin bed in which the Phantom is supposed to rest his weary limbs, and dozens of other interesting features which are flashed here and there on the screen.” The same bed was later used in Sunset Blvd; I would love to know where it is now.

Stage 28 and the remaining parts of the Phantom set have changed quite a bit over the decades. The enormous chandelier, reportedly an exact replica of the one at the Opéra de Paris, had been treated carefully during filming as Universal was nervous about losing such an expensive prop. It remained on the stage until removed for Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain (1966), when it was stored elsewhere at Universal studios, then lost. How a studio loses a 16,000 pound chandelier is beyond me.

The audience seats on the set were removed and a false floor added in its place. In 1938, the studio allegedly installed an artificial pool below the moving floor in the orchestra area of the set. According to Architecture for the Screen, this pool made it usable as another sound studio for recording. Whether there is (or was) a pool underneath Stage 28 is unclear, but there are certainly areas marked on the floor to reveal the location of pits:

A 1980s view of the stage with the pits clearly marked.

A 1980s view of the stage with the pits clearly marked.

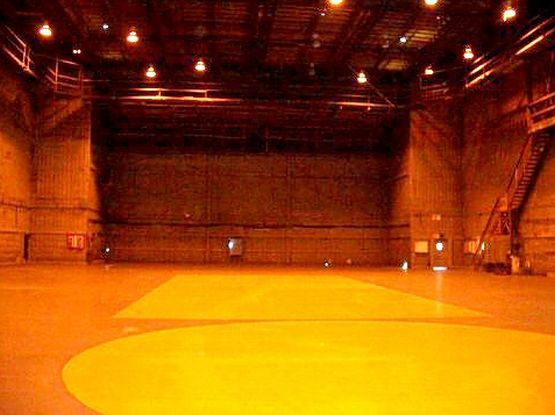

A 1990s view from the other direction, pits marked on the floor in yellow tape.

A 1990s view from the other direction, pits marked on the floor in yellow tape.

Lon Chaney, Sr. is said to haunt Stage 28, his form seen running along the high catwalks, cape billowing behind him. Over the decades, various actors have claimed to have seen Chaney in his Phantom makeup staring at them before disappearing into shadows. Legend also has it that an electrician fell to his death in 1925 during the construction of the Phantom set, and his spirit also haunts the catwalks. Lon’s otherworldly presence would apparently stroll off to haunt his favorite bus bench at Hollywood and Vine, I guess when the Phantom set became too crowded, though once the bench was removed in the 1940s, the sightings stopped. Still, the ghost sightings at Stage 28 continue, as you probably know from watching the hard-hitting documentary television program Knight Rider, specifically the episode “Fright Knight.”

KITT speeds past the old Phantom balconies while other props crowd Stage 28. I wonder how many of those discarded setpieces were from Phantom?

KITT speeds past the old Phantom balconies while other props crowd Stage 28. I wonder how many of those discarded setpieces were from Phantom?

While it’s doubtful Chaney haunts a soundstage, Stage 28 is undoubtedly associated with his memory as of one of America’s most famous and well-loved classic horror actors, as well as a signature role in his career. Yet the set really has not been treated well given its status in Hollywood history. A commemorative plaque was installed on Stage 28 in the 1940s by his son Lon Chaney, Jr., though it disappeared decades ago. Another plaque was added during filming of The Man of A Thousand Faces in 1957, but it is also gone. Most of the set pieces have disappeared over time — you can see that more of the set existed during the Knight Rider episode than exists now.

While only a few walls, some small chunks of the original plaster molding and a few ghost stories remain of such an iconic film, the reality is that it’s more than what exists from most other classic films. Our cinematic heritage deserves more respect, but in the biz, when there’s a war between the economics of film making and the desire to preserve history, preservation rarely wins.

—

Update September 2014: Dennis Dickens Universalstonecutter has shared in the comments a lot of amazing links to his galleries, that include blueprints and pictures I’ve never seen before. Very recommended! Here’s his Pinterest gallery, and his Flickr stream is already linked below.

MORE PICTURES:

Universalstonecutter’s Flickr gallery

The Phantom of the Opera Underground Pool gallery

LINKS:

Stage 28 at The Studio Tour

The Phantom Stage at Silents Are Golden, Michael Blake

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Robert S. Birchard, Early Universal City

Michael Blake, The Films of Lon Chaney and Lon Chaney: The Man Behind the Thousand Faces

Alex Ben Block, Lucy Autrey Wilson, George Lucas’s Blockbusting

Dennis William Hauck, Haunted Places: The National Directory

John Johnson, Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup, and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties

Tony Lee Moral, Hitchcock and the Making of Marnie

Juan Antonio Ramírez, Architecture for the Screen: A Critical Study of Set Design in Hollywood’s Golden Age

Carl Sandburg, Arnie Bernstein, Roger Ebert, The Movies Are: Carl Sandburg’s Film Reviews and Essays, 1920-1928

Anthony Slide, Silent Players: A Biographical and Autobiographical Study of 100 Silent Films

Charles A. Stansfield, Haunted Southern California: Ghosts and Strange Phenomena of the Golden State

Tom Weaver, Michael Brunas, John Brunas, Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931-1946

Great post!

This reminds me of The Happiness Patrol, a fun (and incredibly riidiculous!) serial of Doctor Who. The story was meant to take place in a city and largely its streets., but because the BBC were too lazy I guess to bother filming in n ACTUAL street, the ‘streets’ of this city look nothing like outside streets and more like an indoor studio! haha!

I love watching for obviously indoor “outdoor” shots. I Walked With a Zombie is a great movie, but in the outdoor shots you can actually SEE the walls of the studio!

Great post Stacia, thanks for doing all the hard work.

Thanks, Operator 99!

Pingback: Universal Backlot Blogathon: Saturday’s Contributors | Journeys in Classic Film

WOW! I’m a HUGE Phan! I’ve been obsessed with the Lon Chaney Phantom for YEARS now, and I’ve been on this insatiable question to figure out the exact location of the Phantom’s lair — there seems to be nothing documented about where the lair was — in stage 28 or elsewhere. Can you confirm where the lair was?

If you mean those catacombs (often described as sewers), I’m not sure. There was the one book called Architecture of the Screen by Juan Ramirez which said that they were done inside an area called “Mount Laemmle”, but that’s the only mention I ever found of a Mount Laemmle so I don’t know how accurate it is.

If you mean scenes like where the Phantom is playing his organ and where he gets unmasked, Michael Blake mentioned in his Chaney bio that they were shot on the same stage as the opera scenes, so on Stage 28. But I’m not absolutely sure on any of it! It IS really confusing, as I’m sure you’ve discovered.

Stacia, I’m SO SORRY, I’m just now seeing your reply. Funny, I talked to Michael Blake on Facebook and he said the lake was built where the L.A. River runs along the studio (I doubt that) and that the lair was done on a completely different stage (I doubt that too, since THIS stage was built specifically for the Phantom).

As funny/dorky as this is, I want to build the Phantom stage in all its glory out of Legos!

I recently organized my books which means I have misplaced a bunch (ha!) but I am almost positive Michael’s bio of Chaney said the scenes of the Phantom at the organ were shot on the same stage as the rest of the opera scenes.

The problem is I never know what people mean by “lair.” Some people mean the catacombs flooded with water, others mean the Phantom’s rooms (where the swan bed, organ, etc. are) and others mean both. As you can see, I use the term in this post for both areas. I’m just not sure where the flooded area “under” the opera house was filmed. ETA: The book by Ramirez I mentioned above is on Google Books, but the page with the footnote listing the source of the info about “Mount Laemmle” isn’t included, so unless I find a copy of the book I can’t tell you where the info even comes from. Might have been mentioned in publicity, though.

Well fortunately I’m friends with an independent filmmaker who personally knows one Carla Laemmle. (I’ve been lucky enough to meet her as well). Anyway, I had him has her if she knew anything about Mount Laemmle….. she’s never heard of it. :( Off the subject, when I met her I asked her if she met Lon during production, she said no, she wasn’t allowed to :(

Now here’s the thing….. I gave this some thought last night….. that hill that the Hunchback sets were located on? I think THAT was Mount Laemmle! It’s really the only logical explanation.

See, my thing is, I HAVE to track down the precise location of the lair (where Lon was playing the organ / the unmasking scene). It does make sense to me that it would’ve been in stage 28, but my issue is, I need to know WHERE. With the grand staircase taking up all that space opposite the opera stage and auditorium, WHERE would the underground lake and lair have been located??

I’m all ears to any ideas :)

This might help: Per Google Books, there is a mention of a photo of director Julian near the underground lake on page 133 of American Cinematographer, Volume 70, #9, Sept. 1989. I looked at the article on Questia and there are no pictures so I can’t tell you if it’s helpful or not. I do know the same articles talk about the use of the hill where the Hunchback sets were, so you may very well be right, that the underground water areas were in the hill. The lair scenes, though, couldn’t they have just been set inside the stage, with walls brought in to block the balconies of the opera house? It’s a huge stage — KITT could drive around in it! Ha!

Well see here’s the thing– that hill may have been Mount Lammle, but I seriously doubt the lake would have been built in there….. the scene where Raoul and his brother go after Christine, they end up in that mirror room and Christine has to choose between the grasshopper and the scorpion and she ends up draining the underground lake and flooding the mirror room that Raoul and bro are in — they then go UP, through a hole in the ceiling– putting them smack dab into the LAIR! This tells me VOLUMES! Logically, this means that the underground lake is a controlled tank, something I doubt could’ve been tackled if it was built into the side of a hill; 2ndly, the underground lake and the mirror room were connected, almost like it was one big tank; third, the boys go up into the lair… it had to have been a multi-level set. Logically, it had to have been on stage 28. I agree with you about stage 28 being big enough to house all this awesome stuff, my question has always been WHERE THE BLOODY HECK was the lair situated?? Have you looked at the official studio diagram of stage 28? There’s 2 pits/tanks built into the floor. Based on all this, my guess is the lake was one of these tanks, and the lair itself had to have been located in the “backstage area”, behind where people performed, etc…… Would you agree with that?

Also, have you seen the new Muppet Movie that came out in 2011? When the muppets go to their old theater….. it’s none other than the Phantom set!! They even rebuilt the stage and threw in a chandalier!

What I found about the pits was that they were added in 1938, according to Architecture for the Screen, specifically to make it suitable for a recording studio. I have seen the pits marked out — I have a couple of pics of them in my post as well as the 1938 info.

I have to disagree that the flooded set was attached to the lair. First of all, it’s not the mirror room that was flooded. The “intolerable heat” is in the mirror room (about 1:34:19 on the YouTube copy) then they dig in the sand and find a trap door going down into a smaller gunpowder room. It’s that smaller room that is flooded. We see the two guys in the smaller room with barrels floating around them just as the room fills, then the camera cuts to the lair where Phantom opens a trap door and lifts them out.

It’s all a trick of editing. Since we see no tracking or continuous shot that links the gunpowder room with the lair, I don’t think they were attached. The water the actors are in at the moment the trap door is opened looks to be part of a small, shallow tank, not the gunpowder room itself — I know it was the era of Cecil B DeMille, but I don’t think they would put two actors in deep water in a completely flooded room and trap them there, underneath an enormous 2nd-storey set without escape, stuck until Lon Chaney opened a trap door. That’s exceptionally dangerous, and would cause issues with filming, electricity, possible damage to the floor of the lair because of water lapping up underneath it, etc.

I think we’re looking at the waterways as one set in a location we don’t know yet. Then the mirror room, gunpowder room, various rooms in the lair, backstage at the opera, etc. as all separate sets/rooms, all on Stage 28 from what I’ve read, and footage edited together to make them look like they’re attached even though they’re not. Then the opera house itself, which we know the location of since some walls are still there.

I don’t know if the waterways were a tank, but I would have to assume so. Or maybe a large pool. The gunpowder room that floods definitely looks like a tank, I agree with you there, and the smaller tank that’s like a double-wide bathtub under the Phantom’s lair, too.

Woah, woah, you have access to Architecture of the Screen??? Man, I would give anything to look through that book! Can you please put up some of its pictures on here?

This is intriguing, isn’t it? This issue hasn’t left me alone since 2004. This is one of the main reasons I’m building the Phantom set out of Legos, so I can really figure out the geography of everything and see how it was all put together in its glory.

Okay, so per that book…. the tanks weren’t added til 1938….. are you absolutely sure? Because if stage 28 didn’t, in fact, have any tanks or pits in 1924 for the Phantom, then there’s pretty much no way the lake couldve been on that soundstage and it completely rules that out. Maybe Michael Blake was right; he said the underground lake was the LA River that runs along the property (if you google map Universal Studios you can see it at the top of the property, Muddy Waters Drive).

Also, want to see if you can dig up anything on soundstage 10 at Universal? Per imdb.com, an organ was installed on stage 10 for the lair scenes….. the way they worded this, they make it sound like the organ was put there for audio use on the 1929 reissue, I don’t know if the lair scenes, featuring the organ, were actually FILMED on that stage. Stage 10 is now the audio stage. It’s funny, because like I said Michael Blake told me that Charles Van Enger had told him that the lair scenes were done on a different stage…. possibly stage 10? I asked Michael a couple days ago about that and he said “possibly”, he clearly isn’t interested :)

So can you just confirm for me what Architecture of the Screen has to say about stage 28’s tanks/pits? Btw, this could be something or nothing, but the diagram of stage 28, the modern day diagram shows a turntable right in the area that the opera stage used to be located at….. I have no clue what this means.

In case you missed it, Universalstonecutter below has posted some info about what was apparently called Mount Laemmle. You should scroll down and check out what he wrote.

And FWIW, I’m hoping to snag a copy of ARCHITECTURE OF THE SCREEN for my upcoming birthday, and I’ll tell you what it says then.

I only have the Google Books version of Architecture for the Screen:

http://books.google.com/books?id=Zfw4HQTG3RYC

The artificial lake mentioned is on page 103, which was available for preview when I wrote this post, but it isn’t now. You can still see the sentence if you click the link above and search for “artificial pool beneath” on the left hand sidebar. That sentence leads to a footnote but sadly without the whole book being available I can’t tell you what the footnote is. Sorry that isn’t of more help.

So sad such a beautiful set has decayed to this point, but glad to know that SOMETHING exists! I would love to know where “Mount Laemmle” is. Maybe the lair will one day be found??????

I also hope we find something on those waterways. I think we’d probably need to find publicity from the era, maybe in newspapers or movie magazines, to find more out about it.

Donald, I find your theory absolutely feasible. With hope more information will turn up. It’s sad to think how much of our film heritage has decayed. Of course that is Hollywood, ever changing, always moving. Its a beautiful thing, but bittersweet.

I wanted to follow up/add to my comment from a few days ago….. I looked at the schematic of stage 28 from Universal Studios’ website. Look, I’m no expert on set/soundstage geography, but from camera angles and photos I can deduce that the opera stage was at least a good 30 feet long… there’s absolutely no way the lair and lake could’ve been BEYOND that and Van Enger could still get that wide shot of the Grand Staircase, there’s no way.

Take a look at the schematic:

http://universal.filmmakersdestination.com/site-content/uploads/2013/01/Stage-28-JPEG.jpg

I still don’t know about that bloody turntable (the circle), but I’m gonna assume it’s not here to help me. Anyway, I just rewatched the footage of the areas that lead to the lair… that’s a LOT of space. There’s no way they could’ve put all that stuff into that soundstage.

My original theory from 2004: I always thought that the lair and lake had actually been built UNDERNEATH the opera set, in a “basement” under the soundstage. I mean, as it is, the entire floor of the soundstage is a false floor.

Grrr, this is SO frustrating!!

Pingback: Elsewhere: The Doomed to Repeat the Past Edition - She Blogged By Night

Sept. 2014 the walls are coming down –

Blueprint – Stage 28 Swimming pool

http://www.pinterest.com/pin/349732727286865868/

Camera Shed – on the end of the stage was used for special shots of the stage

http://www.pinterest.com/pin/349732727286865873/

Hi, I just got around to checking these links out, and they’re terrific. I’ve added a link to your Pinterest and Flickr in this post, I hope you don’t mind. Thanks!

UNIVERSALSTONECUTTER, are you very knowledgeable about stage 28? I’ve been asking around and nobody else is responding to me…..

Opera House Cellar – Universal Weekly Vol. 20 No. 22 Jan. 10 1925 page29

“Beneath the original house are five tiers of cellars, the lowest containing a vast subterranean lake.

Note : These were actually built into a mountain [ in 1924 the land for the stage was carved into mountain – that mountain was levelled by earth movers supplying dit to the hollywood freeway contraction]

The article says” trained miners and and mining engineers ” have been brought from the famous Palisade mines in Northern Sierras – excavation required six weeks-

this infers sets and lake were outside next to the stage area ?

source: media history digital library

http://www.pinterest.com/pin/349732727287104838/

http://www.pinterest.com/pin/349732727287104862/

http://www.pinterest.com/pin/349732727287105277/

http://www.pinterest.com/pin/349732727287105244/

UNIVERSALSTONECUTTER — thank you for the links!! The diagram of the exterior of stage 28 (showing the camera shed, etc) is actually driving me nuts — this coincides with what Charles Van Enger says in the audio interview on the DVD about the end of the soundstage left open for the long shots…. but HOW could they have gotten the longshots of the Grand Staircase if the Opera House set was at the end of the soundstage? The Opera House set would’ve been blocking the Grand Staircase.

Do you happen to know anything about the arrangement of the sets INSIDE of stage 28?

Phantom Stage – Mountain aerial

Picture-Play Magazine Sep 1925 – Feb 1926

“Under the little hill in the center of the picture the ground is tunneled into catacombs, which were used in “Phantom of the Opera “..

http://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/pictureplaymagaz23unse_0094

Okay….. the catacombs were built into the side of a hill?! I’m trying to wrap my brain around this. And Carol, I’m dying for info on the Gaby de Lys bed! :)

I know where the Gaby de Lys bed is, I photographed it today. Please contact me at my email address and I can give you the information on it.

WHERE is the bed? (Does anyone know anything about the Phantom’s organ?)

Hey Donald – I don’t think Carol was wanting to reveal that info online, or at least I assume that’s what she meant.

G-darn. Anyway, back to “Mount Laemmle,” yes?

Pingback: Psycho (1960) - She Blogged By Night