This is the SBBN entry for The Late Films Blogathon, hosted by David Cairns at Shadowplay. Check out all the other terrific entries here!

***

Given that one can’t discuss Norma Shearer’s career without the word “nepotism” being uttered at least once, it’s no surprise that her brother Douglas suffers the same fate. His career as the chief sound engineer for Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios was a distinguished one, helping to develop some of the first sound systems for films and ultimately being nominated for an astonishing 21 Academy Awards, winning seven of the statuettes. Yet very little is known about Douglas Shearer, whose career was almost entirely overshadowed by that of his younger sister Norma.

Douglas and Norma examining a state-of-the-art sound camera, circa 1931. Did Norma ever appear in a photo in the 1930s where her hands weren’t on her hips? I submit to you that she did not.

Douglas and Norma examining a state-of-the-art sound camera, circa 1931. Did Norma ever appear in a photo in the 1930s where her hands weren’t on her hips? I submit to you that she did not.

It’s not that MGM publicity didn’t try to set Douglas apart from his more famous sibling. In 1931, author and screenwriter Donald Henderson Clarke was deployed to write a brief bio that began with a lament that Douglas was actually hindered by his better-known sibling. Still, even gossip columnists mentioned the Shearer family business, often under faux positive guise of “the building of dynasties”, a way of saying “nepotism” without getting Louis B’s boys breathing down your neck.

Douglas Shearer was born in 1899, and by the mid 1920s, had joined his mother and Norma in Hollywood, where she was already under contract with MGM. He got a job in the technical department at MGM, and found himself intrigued by fellow engineers working to perfect sound in film. In 1928, he was the sound recorder on MGM’s first sound film, White Shadows in the South Seas (1928). Tasked with adding some music and a few sound effects, Shearer had to take the finished film across the country to a sound lab to finish the job, MGM still not having the necessary tech.

Douglas Shearer and Ramon Novarro during filming of Son of India (1930).

Douglas Shearer and Ramon Novarro during filming of Son of India (1930).

Within a year Shearer was credited with inventing the “camera bungalo,” described as “a device to silence the camera motor.” Though little information about this “bungalo” exists, it was likely one of many blimps or booths used by studios in an attempt to prevent the sound of the camera whir from being heard on the film’s soundtrack. Soon Shearer was made the head of the entire recording department at MGM, and given a large, soundproof office where speakers carrying sound from every single soundstage on the lot could be turned on with the flip of a switch. From this central location, Shearer would listen in to recordings and supervise multiple films at once.

Douglas apparently played well with Louis B. Mayer, which is not exactly something that could be said of everyone at MGM, and the few mentions of the head of the sound department in contemporaneous magazines indicate he deftly managed the Hollywood political scene. In what may not be an unrelated anecdote, Leatrice Joy recalls in an interview for Hollywood Remembered that director Clarence Brown knew that actor John Gilbert’s voice in the infamous early talkie flop His Glorious Night didn’t actually sound like Gilbert, so he asked Douglas Shearer what happened. “You know,” said Shearer, “We forgot to turn up the bass.”

As is true today, there was little interest amongst movie fans in the technical work behind the scenes, and in 1931, Shearer may have considered that a blessing. On June 6 of that year, Douglas informed his wife Marion that he had been having an affair with MGM staff writer Ann Cunningham, and asked his wife for a divorce. Instead, Marion went to a carnival shooting gallery, shot some figures off a shelf, then shot herself between the eyes. Obligingly, the newspapers reported that she had been in ill health for some time, and that the family was aware that her health was frail but didn’t realize she was succumbing to “melancholia.” Doug waited the obligatory year before marrying Cunningham.

Just over two decades later, Douglas Shearer would work on his final film for MGM, Her Twelve Men (1954), though he stayed on as director of technical research at the studio until 1968. Truth be told, Her Twelve Men was actually the next-to-last filmed project Shearer worked on, but the final film, a short titled “Poet and Peasant Overture” (1955) featuring The MGM Symphony Orchestra, is unavailable.

Her Twelve Men is a curious film in that it manages to be a low-rent Tea and Sympathy two years before Tea and Sympathy was released. Based on the novel by Louise Baker published in Ladies Home Journal in 1953, Her Twelve Men stars Greer Garson as Jan Stewart, a newly-hired teacher at a mid-tier private boys’ school. The complication in this film is that Miss Stewart is female. That’s it. That’s all there is to it: “Can a woman be a teacher and supervisor to a dozen pre-teen boys?” the film asks heroically, or something.

The film is intent on pestering the audience throughout with the, ahem, “fact” that men are better than women at anything and everything. As I mentioned a few days ago in my blurb on The Assassination Bureau (1969), films like these are essentially instruction manuals for social behaviors. A woman is to be obedient, malleable and pleasant, and in the case of Her Twelve Men, this was part of the original story, not something added by the studio. Author Louise Baker, around the time of this film’s release, spoke to a high school audience, telling them, “most of my heroines end up in the kitchen where I suppose they should be.”

Baker was not content with merely being judgmental; she could also be incredibly tasteless, making sarcastic cracks about her physical impairment — she lost a leg when she was eight years old — and constantly referring to herself in interviews as old, plain, boring, and unattractive. This attitude pervades her book Out on a Limb, with a title that can easily be taken as yet another cheap crack at her own plight. If I can be so bold as to interject a personal note, the night after I read few interviews and snippets of Baker’s writing, I had a distinct nightmare about people who had lost a limb being forced to endure snotty sitcom puns about their injuries.

It seems Greer Garson was none too pleased with this film, either. Screen World’s Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors notes Garson, fully aware that she was no longer a box office draw, asked to be released from her MGM contract after this film. “I haven’t been happy with the kind of pictures I’ve been receiving lately,” she reported in an interview after leaving MGM, though it should be noted MGM was somewhat stymied, given that Garson was no longer a bankable star. The public had tired of her; an AP article in 1953 referred to Lassie as “Greer Garson with fur,” which is astonishingly bitchy but also indicative of how the public felt about Garson around the time of Her Twelve Men.

Miss Stewart during one of her girlish daydreams which open the film but are then never referred to again, not even obliquely.

Miss Stewart during one of her girlish daydreams which open the film but are then never referred to again, not even obliquely.

In this film, Miss Stewart is portrayed as a woman without a proper role in society, a recent divorcee who had well-placed friends get her a job as a teacher, despite having no experience. The heavy implication is that her lack of children is actually the bigger problem, and fellow schoolteacher Joe Hargrave (Robert Ryan) spends a lot of time acerbically informing Miss Stewart of her lack of motherly love. Meanwhile, the beautiful rich woman Joe dates throughout is treated with nothing but contempt by Joe, because a woman with money and beauty who owns her own sexuality is a threat. He, of course, is more attracted to Miss Stewart, but has to insult her and show her up for the bulk of the film, show his dominance first, which she of course responds to. There is also the headmasters Dr. Barrett (Richard Haydn) who is coded as gay, who Hargrave shows dominance over as well. It’s unpleasant.

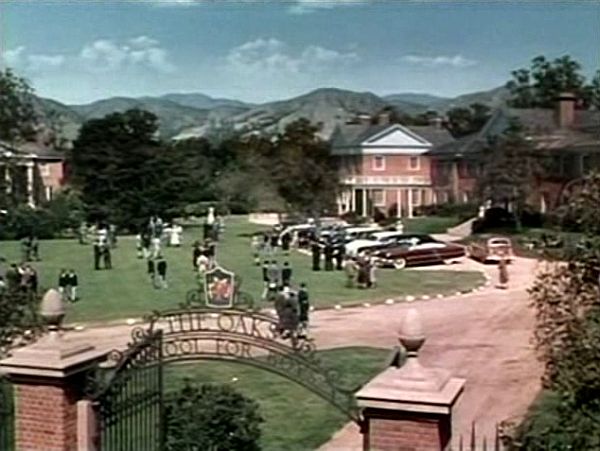

The Oaks School for Boys, as seen in the days when cars were as large as administrative buildings.

The Oaks School for Boys, as seen in the days when cars were as large as administrative buildings.

Meanwhile, the kids are generally good actors, given reasonably believable concerns and behaviors. In fact, Her Twelve Men is probably best known for being the movie where child actors Tim Considine and David Stollery first met; they would go on to play similar characters known as Spin and Marty on “The Mickey Mouse Club.” The Spin and Marty shorts bore quite a bit of resemblance to Her Twelve Men, with plot points taken from outdoor and horse riding scenes in the film and recycled for the MMC segments.

Early in the film, Miss Stewart muses about her childhood daydreams, the fabulous things she thought she would be able to do as an adult. These colorful segments are orchestrated by the always terrific Bronislaw Kaper, the score sounding wonderful through MGM’s sound system and Douglas Shearer’s supervision. The sound recording is high quality throughout, the practiced and professional sound you expect to hear in a mid-50s MGM film. They did have a slightly superior sound quality over other studios. Take for example Sincerely Yours (1955), which appeared on SBBN previously. The live musical performances sound great, the best of any Warner Bros. musical of that year, yet it still wasn’t as polished as MGM’s audio.

And MGM’s dubbing was better than other studios, too, though was still obtrusive. There’s an echo in the outdoor scenes that places them firmly indoors on a set. There are also some strange dubbing choices, such as the boys’ puppy whining for no reason, when he’s just being held, drinking water or chilling out. It’s distracting and a little upsetting; we’re designed to respond to cries of distress, of course, so why anyone at MGM would choose to dub in sad puppy dog whining and why Shearer would sign off on it is a mystery.

After this film and the following year’s MGM Symphony short, “Poet and Peasant Overture,” Shearer was replaced by Wesley C. Miller as sound recording supervisor. Miller had worked with Shearer as far back as 1929 on Broadway Melody, held at least one MGM sound system patent and was quite experienced, though there was a bit of trouble during the transition. Interrupted Melody (1955), for example, was to feature the musical numbers as sung by Marjorie Lawrence, the subject of the film. But despite recording twice with a live orchestra, the sound wasn’t good enough to be used for the film, so MGM singer Eileen Farrell was hired at double salary to provide new audio, all uncredited to save Marjorie Lawrence’s feelings. Lawrence went public anyway, momentarily embarrassing MGM.

That said, most of Miller’s post-Shearer work is impressive: Think of the Bill Haley and the Comets introduction to The Blackboard Jungle, or Doris Day’s vocals in Love Me or Leave Me, or the crisp audio in Bad Day at Black Rock and Moonfleet. It seems Shearer, as instrumental in the development of cinematic audio techniques as he was, left just as a new, more technically proficient generation was about to reign.

Pingback: The Late Show | shadowplay

This will sound churlish of me, I know…but my favorite Shearer pictures are the silent ones, where I don’t have to hear the nepotism in her voice.

Hey, you were right, kiddo…you can’t mention Norma’s career without using the word “nepotism”!

(And the “hips” thing. Hilarious if true.)

The most hilarious things are ambiguously true.

I am once again in awe of your research, knowledge and insight!

Thanks much!

I most heartily agree with your assessment.

Thanks for this fascinating insight into a Shearer we hear so little about.

I like Her Twelve Men.

Thanks, Vienna!

Question: I haven’t seen John Gilbert’s early talkies, but find him intermittently good in the later ones. In Queen Christina he does seem kind of camp, but I like him in The Captain Hates the Sea. Do we believe the stories about bad/faulty/sabotaged sound recording in the first talkie? Have you seen it, and is his voice all treble? I’ve read a lot of accounts that put the problem down to over-enunciation, making him sound fey.

I’ve seen a clip of it (in Brownlow’s HOLLYWOOD, if I recall) but it’s been so long ago that I just don’t remember much, other than all the voices sounded very tinny. When I was poking around about Leatrice’s story for this post, I found a million theories on what happened, everything from the stilted satiric dialogue being played straight to tech issues to actual sabotage.

It would surprise me if Louis B. released a bad movie on purpose just to take down a star (surely there were cheaper ways?) but it sure seems odd that he threw some mid-level crew and unknown actors into an allegedly important sound film with Gilbert as the star. But I suppose that might have been the result of Gilbert asking that his real first sound film, REDEMPTION, never be released; Mayer may not have wanted to possibly “waste” another good cast like in REDEMPTION.

For what it’s worth, in 1931’s WEST OF BROADWAY and GENTLEMAN’S FATE, his voice is just fine, but the fact that he’s in those movies as support to El Brendel and co-starring along Marie Prevost (another silent star whose career tanked about the time Gilbert’s did) shows how far his star had fallen by then. The camp in his voice in QUEEN CHRISTINA is affected, I think, because it’s hardly there in his 1931 films.

Excellent entry and a lot of interesting information– despite this, I gotta say I don’t see “Her Twelve Men” in anywhere as negative light as you do here. In fact, I came to this piece BECAUSE I enjoyed “Her Twelve Men” and wanted to know more about the film. I’m not suggesting that it doesn’t have its issues or suffers from some antiquated ideas, but I found that in its own stilted way to be emotionally genuine. The picture actually seemed to me about Garson’s character learning to re-imagine and her future more than anything else. I don’t know. Perhaps reading about Baker, along with providing nightmares, also left an awful lingering taste on your sense of the film.

Norma Shearer was much more competent an actress than the world gives her credit for.

I find ” The Divorcee” and ” Let Us Be Gay ” utterly charming.

She knew her audience and played her gamine parts with full throttle.

Unless you were a theatre goer in 1930’s , it is completely impossible to look back at many Shearer, or Crawford , or Garson films with such jaded eyes.

The public, not nepotism, gave her her rightful due and her deserved place in film history.