In 1899, the light musical Florodora opened at the Lyric Theatre and took London by storm. A year later, Florodora would open on Broadway, and New York City became just as smitten with the musical’s starring sextet of female leads as London had. Known as the “Florodora Girls,” the women — the original six as well as their eventual replacements — were the hit of the season. The play closed in 1902, but thanks to the charm and beauty of the Florodora Girls, their reputation lived on. Revivals were staged and newspaper ran “Where Are They Now” stories on the original six for decades.

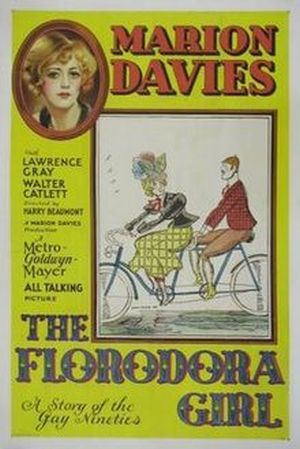

Not precisely a revival nor a biopic, the 1930 Marion Davies vehicle The Florodora Girl takes little more than a name and the vague idea of a Florodora Girl and transplants her into pre-Code Hollywood, and to strange, though not uninteresting, effect. So light at times that it looks as though it will blow away, reviewer Creighton Peet of The Outlook dubbed The Florodora Girl as “completely delightful nonsense.” [1]

Though it was her third foray into talkies, Davies was still obviously ill at ease in Florodora Girl, though quite a bit was done to play to her strengths. There’s an extended musical number where she gets to pantomime, though what looks charming in a silent looks odd in a talkie. Plenty of very funny contract players surround her; Walter Catlett (who always looks like Harold Lloyd’s drunken uncle) and Louis John Bartels are especially good here. Her frequent co-star Lawrence Gray is here, too, giving a surprisingly solid performance, and with a singing voice that reviewers praised at the time.

It all adds up to a light musical romantic comedy that wants only to entertain you, and blows raspberries at anyone who expects more. Florodora Girl cheerfully, even defiantly, steals from pretty much everything, including the Clara Bow hits Wings and It (both 1927), The Freshman (1925), and I think I even spied some stolen staging from Blonde for a Night (1928). But that’s okay, Bringing Up Baby (1938) and Sporting Blood (1931) borrow from Florodora Girl. All’s fair in love and film.

Speaking of Marie Prevost, there is more than one moment in this film where Davies’s mannerisms look so close to Marie’s that it’s uncanny. I think, if one were the kind of person to analyze this, and for good or ill I am that kind of person, it’s not so much a case of imitation but a product of the times. The double take, the giggle and shrug, the side-eye, the long wide-eyed stare, they’re all major players in the Mack Sennett Comedy Playbook (and Restaurant Guide) [2], and much of this film feels like a feature-length Sennett farce.

That was a fact not lost on reviewers at the time, like my beloved Mordaunt Hall, who noted that the film is “virtually a travesty, but one that is shrewdly directed with a good sense of humor… It is a picture that has a scoundrel, one named Fontaine, who twirls his dark mustache and sniggers as he is holding Daisy in his arms.”

It’s all true! A moustache gets twirled! The folks involved in this film knew damn well the script was ripping off other popular films of the last few years and decided to make the best of it. Many scenes are directed like Sennett shorts, and no one gave a damn that a film made in 1930 about the Gay Nineties using late 1910s comedy tropes was the exact kind of anachronistic tomfoolery that would make an audience’s head spin. Lots of scenes are improvised, too, especially the Coney Island scene. Watch for the moment where a crew member is standing right in front of the camera before he’s told to move out of the way. The editor just left it in!

How the script got to this point is a mystery, considering the writing talent behind it. Ralph Spence would co-pen Way Out West the same year, and Gene Markey, head writer, would go on to write the screenplays for Midnight Mary, Baby Face, Female and Fashions of 1934, one right after the other. That is a hell of a run.

Markey’s pre-Code sensibilities are all over Florodora Girl, especially in the snappy dialogue spouted by her two friends Maud (Vivien Oakland) and Fanny (Ilka Chase; you know her as Lisa Vale in Now, Voyager) and as they talk about the men they, er, dated to completion. “I lost a lot of sleep gettin’ that hardware,” says Fanny as she lends Daisy some of her expensive diamond bracelets.

That’s not only another datapoint for my Defiant Anachronism Theory of The Florodora Girl, but a good example of why the original Florodora Girls were so taken aback by the film. Jeff Cohen at the terrific and very sadly missed Vitaphone Varieties has a fine write-up on the Florodora Girls, and notes that a woman named Daisy was indeed one of the original American sextet. However, Davies’s character wasn’t based on her in any real sense, and as Marjorie Relyea, another original Florodora Girl, said in a 1933 interview, “All the girls in the sextet were ladies in the real sense of the word. The movie produced several years ago was centered around the sextet, wasn’t true at all. We have all been indignant over it. We were never that type of girl!”

The big finale of The Florodora Girl is the two-tone Technicolor reel, featuring authentic staging of the Florodora hit “Tell Me Pretty Maiden.” [3] As Vitaphone Variety notes, the backdrop is a solid reproduction, but the song has been significantly shortened for the film, and the stage isn’t even close to the same size, the original being very tiny.

The Florodora Girl did not fare well, which many have attributed to the film being a real stinker, though it isn’t and for precisely the reasons critics said at the time: it doesn’t take itself seriously. Some of the reviews of the day were probably Hearst-sponsored, though when Louella Parsons said Marion never looked lovelier, she may have gotten a little cash encouragement for saying so, she wasn’t wrong.

Richard Barrios notes that Florodora composer Leslie Stuart sued MGM for copyright violation, and the film was saddled with what Barrios called “Hearstian meddling,” and those facts alone kept the film from being released as widely as it should have been. Davies’s performance is usually blamed, though she’s not bad, she’s just out of date. She also exhibits that common trait in silent stars who moved on to talkies: you can see her potential in the new medium, but for whatever reason — and a million reasons have been put forth over the years — she just doesn’t quite make it.

Warner Archive has released The Florodora Girl on MOD DVD. It’s a bare-bones release though in pretty good quality. There is a musical number taken from a source that needs a bit of work, and a little fading of the blue in the Technicolor sequence. Some of that seems to be intentional and original to the film to give it a lovely pastel look.

–

[1] The Outlook, June, 1930 (PDF)

[2] This is not a thing, it an attempted joke.

[3] Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre, by Ethan Mordden

Featured image courtesy Doctor Macro.