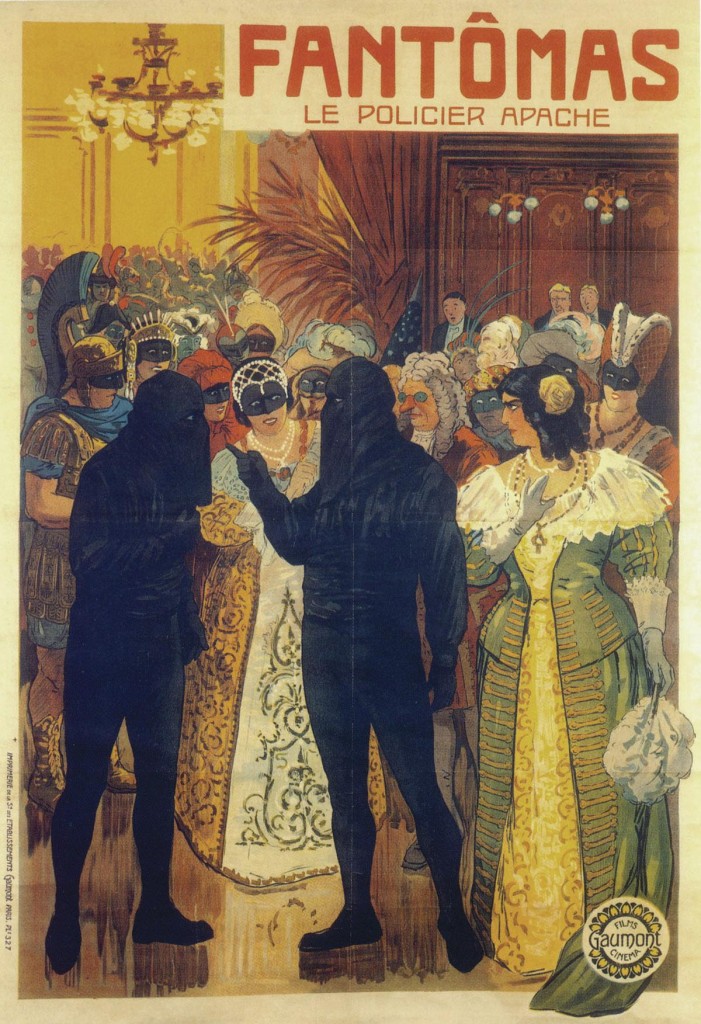

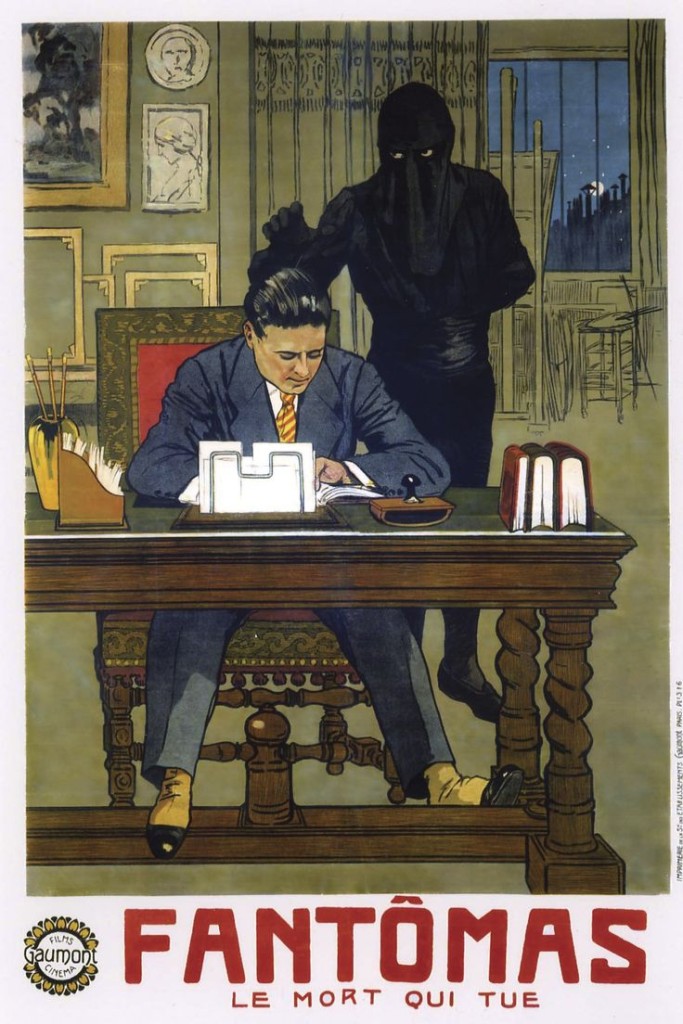

Fantômas, a series of five films by Louis Feuillade released in 1913 and 1914, follows the eponymous criminal as he steals, seduces and murders his way through Paris. Based on a popular pulp novel series of the same name, the charm and appeal of Fantômas to the public was his almost supernatural talent at disguise. This is a famous international criminal who, implausibly, has no identity; it’s as if he doesn’t even exist.

Kino Lorber has released Fantômas on DVD and Blu-ray in what is an astonishing print. The 4K restoration courtesy Gaumont and The Centre National du Cinema is gorgeous, and is far clearer and more appealing than many modern films which have been released on Blu-ray. The details are incredible, offering fantastic looks at the fashions of the day; the individual stitches are visible on the handmade needle lace adorning Princess Danidoff’s gown at the opening of the film, and it’s enough to make you gasp right out loud.

This is entirely as it should be, however, as the Gaumont studio was known for the beautiful visuals of their films. As David Bordwell notes, “[Léon] Gaumont took pride in his films’ crystalline photography, achieved largely by shooting in daylight, both in exteriors in and sets built in the glass-walled studio.” The only downside to this stunning restoration is that you can see the rather casual attitude filmmakers had toward preserving the set. Scrapes, chips and dents from rough handling during set-up abound, as does a significant amount of dust and paint splatter on the floors.

Starring René Nacarre as the mysterious Fantômas, the series follows his crimes, his captures (and inevitable escapes) from the dogged Inspector Juve (Edmund Bréon), who is somewhat oddly often accompanied by his journalist friend Jérôme Fandor (Georges Melchior). Each film is roughly one hour in length, give or take, and the entire series of Fantômas’ shenanigans runs at five and a half hours.

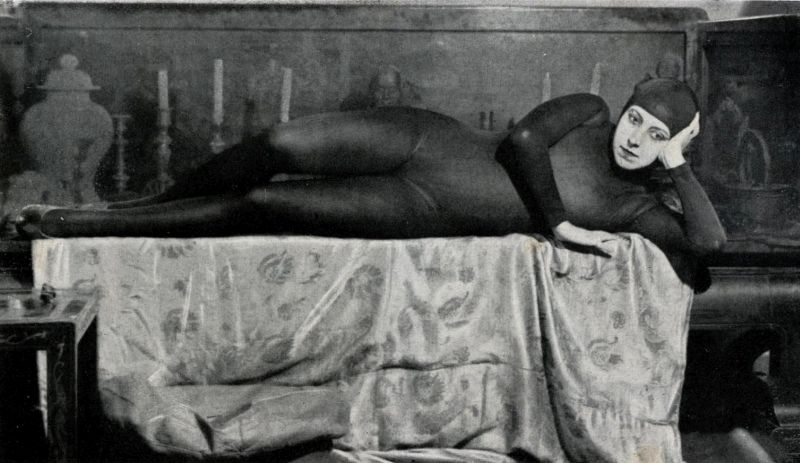

All of the serials of Louis Feuillade were popular and highly influential in their day, especially Fantômas, and especially amongst the Surrealists. Though many Surrealists such as Robert Desnos and Max Ernst were inspired by the original series of Fantômas novels, the Belgian painter Magritte was taken with the film versions of these European crime serials. Fantômas was not the only serial that fascinated him, as his repeated use of large silver bells in his paintings attest — scholar Jose Vovelle traces these back to a scene in Mabuse the Gambler — and Magritte reportedly even dressed up his wife Georgette as Irma Vep from Feuillade’s Les Vampires and photographed her in a version of this famous portrait of actress Musidora. [1]

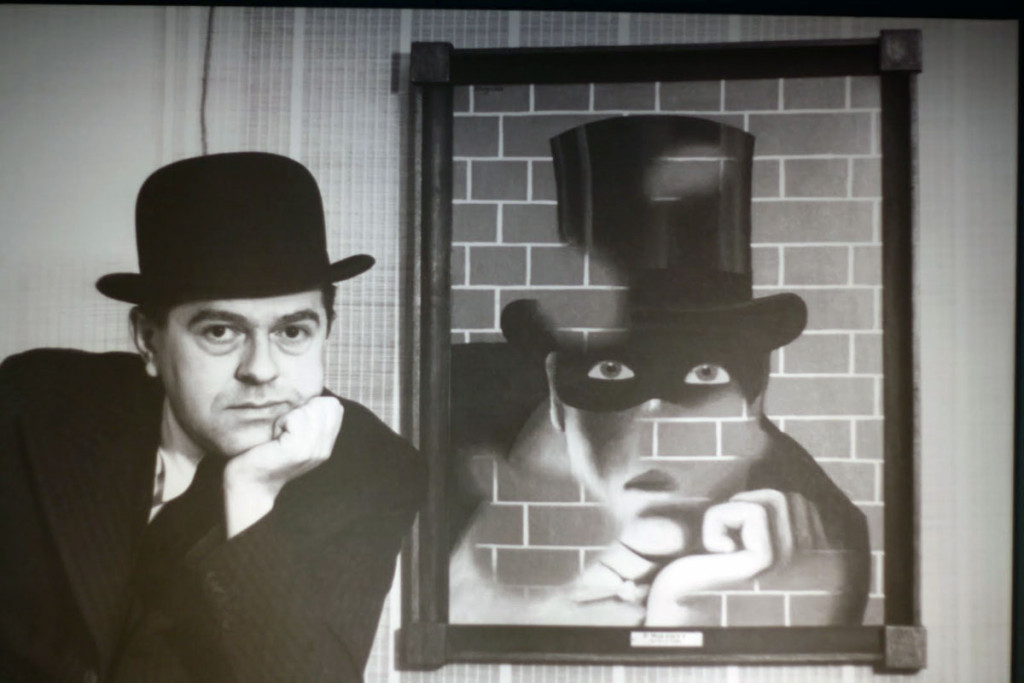

Still, it was very likely that Fantômas was the serial that most fascinated him. His painting The Menaced Assassin from 1927 is one of the earliest of Magritte’s works which unquestionably show his fascination with the imagery of Fantômas. A publicity still of two criminals waiting on either side of a door, hidden to their intended victims but visible to us, inspired the artist’s own take on paranoia, voyeurism and suspense.[2]

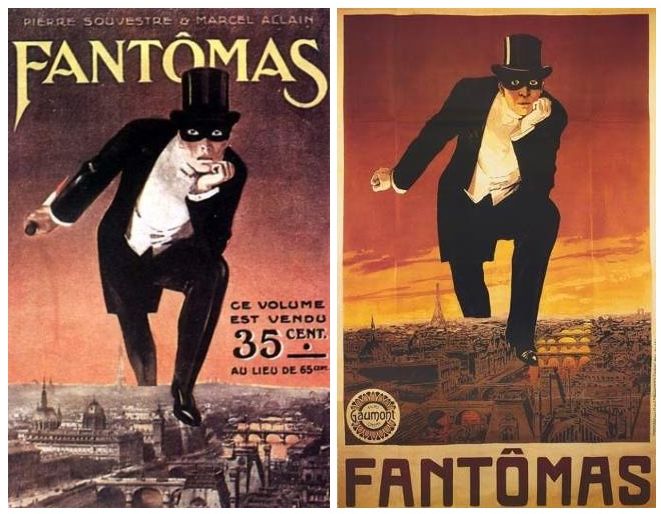

Magritte posing with his 1938 work The Barbarian (above). He used the image of Fantômas as seen on the pulp novels, rather than the tamer version of the master criminal that appeared on the Gaumont poster.

This poster is, in fact, the first clue that the Fantômas series had been somewhat toned down and sanitized for film audiences. The poignard of the original artwork has been removed, as has the gender ambiguity, which had been surely referring to the fact that Fantômas disguises himself as a woman at times. Much of the violence of the original novels, which could be random and harrowing, was softened for the films, and the ideas of corruption amongst judges and police officers were made less obvious, though still played a large role in the serial. These changes were made with the full cooperation of French writers Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, the duo who wrote the Fantômas books. Not only did they work closely with Feuillade to develop a script, they improvised new scenes before and during filming.[3]

Despite their initial popularity, the Fantômas films essentially disappeared until Henri Langlois programmed a revival of the series, along with Les Vampires, Judex and Tih Ming, at Cinémathèque Française in 1944.[4] On its original release on the eve of World War I, audiences enjoyed the antisocial nature of the tales of the master criminal, the subtle hints at class consciousness, the police being foiled and the rich being robbed. Its revival during World War II appealed to those interested not only in the sociocultural themes but in the mechanics of filmmaking, and of Feuillade’s “delirious mise-en-scene,” as J. Hoberman described.[5]

Shot in what we might call a documentary style nowadays, with cameras seemingly bolted in place, designed to capture all the action within the frame, Fantômas can be a bit of a challenge for those new to silent cinema. The films are fun to watch, but those not used to some of the quirks of early cinema — actors looking at the camera, floppy sets, hilarious blocking — might prove irritating. That said, these things (accidentally) give Fantômas its realistic feel, most notable in the outside scenes. For the folks used to such things, and those willing to stick with the idiosyncrasies of early cinema, Fantômas will not let you down.

For more technical details and screencaps of the Blu-ray, visit Blu-ray.com.

—

[1] Surrealism: Surrealist Visuality, by Silvano Levy

[2] Pulp Surrealism: Insolent Popular Culture in Early Twentieth-Century Paris, by Robin Walz

[3] The BFI Companion to Crime, by Phil Hardy

[4] Cinephilia and History, or The Wind in the Trees, by Christian Keathley

[5] The Village Voice Film Guide: 50 Years of Movies from Classics to Cult Hits

The Cinema Alone: Essays on the Work of Jean-Luc Godard, 1985-2000, edited by Michael Temple, James S. Williams

Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging, by David Bordwell