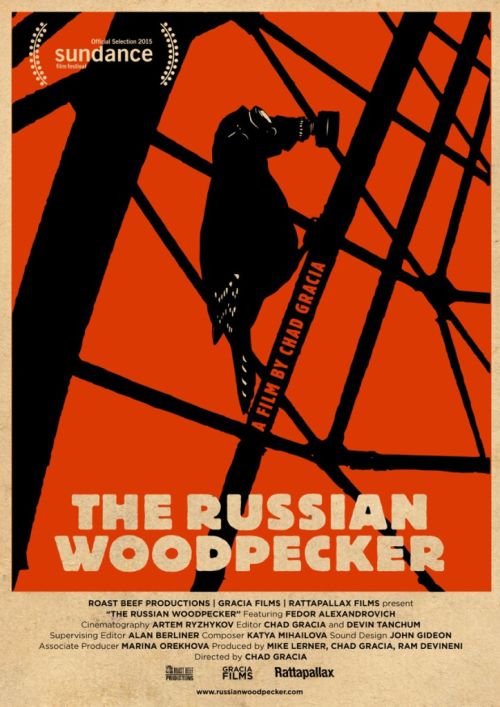

For over a decade, the U.S.S.R. operated an enormous, expensive, high-tech early-warning radar system known as the Duga. After a series of smaller prototypes were successfully tested, the first of the gargantuan 500-foot-tall steel structures was constructed near the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, and launched on July 4, 1976, surely as a sly joke. The mysterious tapping sound emitted by the Duga spawned a series of conspiracy theories and a clever nickname: the Russian Woodpecker.

Days before this Duga transmitter near Chernobyl was to undergo its final inspection, the nuclear power plant suffered a catastrophic accident, rendering the plant and surrounding area — including the Duga — radioactive. Though many adults stayed, nearly all the children in the area were evacuated to orphanages for their safety. One young boy, Fedor Alexandrovich, never recovered from the physical and emotional trauma. Nearly 30 years after the disaster, Fedor, along with friend and cinematographer Artem Ryzhykov, attempt to piece together just why the Chernobyl disaster happened, and if the great glowing wall of steel known as the Duga had anything to do with it.

The Russian Woodpecker, the most recent documentary from Chad Gracia, follows Alexandrovich’s quest for the truth, focusing mostly on a series of interviews with former Soviet engineers and politicians involved in both the Duga’s classified monitoring of worldwide missile and submarine launches. Yet it’s Fedor himself who attracts the most attention, and it’s no wonder. It would have been all but impossible for the film to not focus on the frazzled artist Alexandrovich, with his meme-ready face and the demeanor of an Eisenstein antihero, albeit one whose personality curiously changes when he doesn’t realize the cameras are rolling. However, it may have very well been a better film without the input of the wide-eyed artiste. His theory is implausible, but that’s never detracted from a good documentary before; what detracts here is Feodor’s lack of commitment to his own constructed narrative. His side-eyes to the camera when an interviewee starts going all Stalin on him are entertaining, certainly, but the fidgeting, the sighs, the uncontrolled impatience on display even during interesting moments make you wonder why he ever decided to do this in the first place.

Once the inevitable paranoia strikes, Alexandrovich wonders the same as well, and his floundering bravery causes Ryzhykov to attack. Yet what, exactly, was Fedor accomplishing before his fear kicked in? The artistic output the Duga inspired in him was almost pathetically derivative — at one point, he seems to borrow imagery from the famous “1984” Apple commercial, of all things — and the world already knows that there are Soviet hardliners still praising Stalin to this day. Hell, half of all American political thrillers made from 1990 through 2016 inclusive depend on this bit of knowledge.

Still, it’s that connection between the corrupt past and the corrupt neo-Soviet present that gives The Russian Woodpecker its heft. The film never unearths anything startling, and its attempts to fool you into thinking it has are done in bad faith, but the film remains a compelling reminder of just how quickly we humans tend to fall back into old habits, even old habits that are likely to kill us. The Euromaidan protests, where Alexandrovich first announces his conspiracy theories and where Ryzhykov was wounded by police, serve as an effective backdrop for the Duga conspiracy, but more importantly, as a chilling warning to those unwilling to heed the lessons of the past.

The Russian Woodpecker premiered at Sundance in 2015, winning the World Cinema Documentary Grand Jury Prize there, and continued on to nominations and wins at several international film festivals. Kino Lorber has released the film on DVD with a host of fine extras, including deleted scenes and two featurettes: “Climbing the Duga” and “Dreams of Fedor.” There are subtitles, but note that the English subtitles are for the Russian-speaking parts only; when English language news clips are used, no subtitles are available.