Susy (Audrey Hepburn), recently blinded in a car crash, has just married brusque photographer Sam (Efrem Zimbalist Jr.). When Sam brings home, and then loses, a doll handed to him by fellow airplane passenger Lisa (Samantha Jones), he has no idea the kind of trouble he’s caused. Inside the doll was a stash of drugs that belonged to a man named Roat (Alan Arkin), and when he realizes where his drugs are, he forces Lisa to try to get them back. When that plan doesn’t work, he calls on two of Lisa’s former partners in crime, Mike (Richard Crenna) and Carlito (Jack Weston), to terrorize Susy and find the lost doll.

Sam is a character I will forever love to hate. The beautiful Lisa (above) knows he’s an easy mark to pass her heroin-filled doll to, because she’s seen him flirting with the stewardess and figures he’s a pushover for a lovely lady.

Sam is a character I will forever love to hate. The beautiful Lisa (above) knows he’s an easy mark to pass her heroin-filled doll to, because she’s seen him flirting with the stewardess and figures he’s a pushover for a lovely lady.

Wait Until Dark (1967) is a tense and effective psychological thriller notable for its fantastic performances and unique look. Cinematographer Charles Lang had a knack for making even the dullest scenes pop; as much I love films like Blue Hawaii and The Wheeler Dealers, I know that the bulk of their charm lies in how they were filmed. In Wait Until Dark, Lang, along with set designer George James Hopkins, make Susy’s and Sam’s slightly dingy basement apartment both realistic and romantic, showing the cracks and the rust and the built-up grime in between the beautiful vintage wrought-iron sewing table, vases of flowers and bright and (somehow) airy bedroom.

Warner Archive has just released Wait Until Dark on a truly beautiful MOD Blu-ray, newly scanned at 2K with color correction and cleanup. It comes with English subtitles (good ones, too, not the summary-style subtitles that used to be the industry standard), theatrical trailer and an 8-minute featurette. I always thought the film looked good both on TCM and in the most recent DVD release, but this restored release is just phenomenal, especially in the audio and the rendering of the subdued palette.

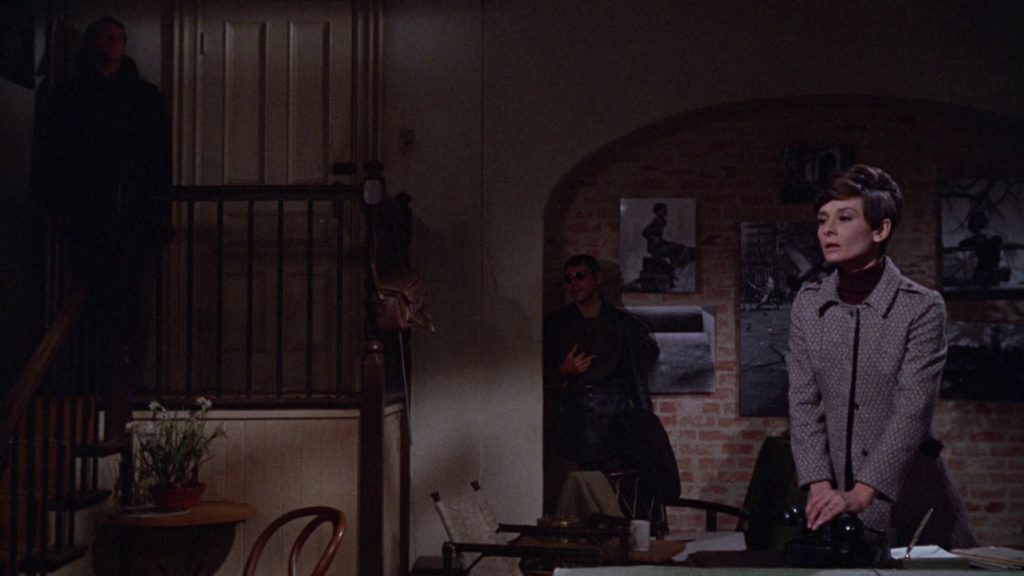

This is one of my favorite scenes of all time: Mike and Carlito try to take on Roat while using some of Sam’s photography equipment as weapons. Note the tripod used as a spear, and the camera and strap used as a morning star. Truly bonkers. I love it.

This is one of my favorite scenes of all time: Mike and Carlito try to take on Roat while using some of Sam’s photography equipment as weapons. Note the tripod used as a spear, and the camera and strap used as a morning star. Truly bonkers. I love it.

It’s true that in 1967, the idea of a sociopath terrorizing a blind woman just because he has the opportunity to do so was not a common one, though by that time in history a few Bond villains and some B-movies had started to break ground in this area. Roat’s plot to get the heroin-filled doll from Susy’s apartment is difficult to suspend disbelief for because it’s unnecessarily complicated, but as is obvious from the second he walks into Susy’s apartment, Roat’s a psycho, and psychos gotta psycho. Mike and Carlino go along with the plan, Mike pretending to be an old friend of Sam’s, Roat playing a version of himself and his father, and Carlino pretending to be a detective.

It doesn’t take Susy long to realize that Roat and Carlino are up to something, but it takes her forever to even consider calling for help. The big question with viewers is always, “Why didn’t she just call the police?” and Sam’s creepy behavior is the answer. He pushes a pathological need for self-reliance onto Susy, wanting to turn her into “the world’s champion blind lady,” and isolates her with only an unreliable young girl for help; he himself will not help his wife at all, not even the normal sorts of things partners help each other with around the house. He also regularly accuses her of lying, though he never has any reason to think she’s a liar.

Susy’s story about how she and Sam first met only a year earlier really solidifies the fact that she’s been trained to do two somewhat contradictory things: follow Sam’s orders to the letter, and cope with every problem on her own. Thus, when she asks for help, she feels uncomfortable, embarrassed and weak, and ends up choosing to investigate and deal with this crazy con herself.

Hepburn gives one of her best performances here, I think, and was nominated for an Oscar for her role. Alan Arkin is beyond fantastic as the sociopath who just really enjoys bein’ himself: tormenting people and saving money by buying his murder-and-robbery gear in bulk. He wasn’t nominated for anything, which was a major oversight; even more inexplicable is how Zimbalist was nominated for a Golden Globe. The same goes for director Terence Young (Soleil rouge, Dr. No, Mayerling) who makes this very stagey play into something dynamic yet claustrophobic.

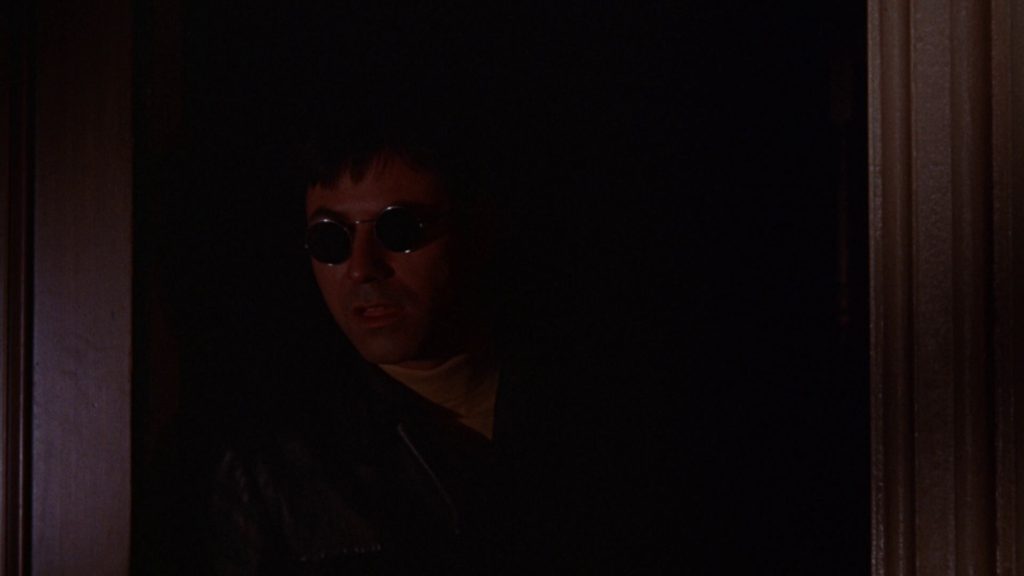

Entire sequences are filmed in the dark or with just the tiniest pinpoints of light. These are screengrabs from the Blu-ray but they don’t do the film justice, which is entirely my fault and not the fault of the transfer.

Entire sequences are filmed in the dark or with just the tiniest pinpoints of light. These are screengrabs from the Blu-ray but they don’t do the film justice, which is entirely my fault and not the fault of the transfer.

For those of you who haven’t seen Wait Until Dark before, you are in for a treat, especially from the film’s famous finale, which some reviewers have noted would not work on today’s experienced audiences. I disagree. I said it years ago in a little mini review and I’ll say it again: even if you’ve seen the film before, the finale could very likely give you an infarction! Happens to me every time. Wait Until Dark is a great film, one of the best psychological thrillers to come out of this era.

Lovely review. As to whether it works for modern audiences I have a little experience in this area. I happened to see this and Psycho on back to back nights at my local college theater (FSU) a couple of years ago with an audience made up almost entirely of college kids. Psycho certainly got a visceral response but NOTHING like Wait Until Dark. By the climax, the entire theater was screaming. Even I was gasping and I’d seen the movie more than a dozen times (though never with an audience). Critics need to get out more.