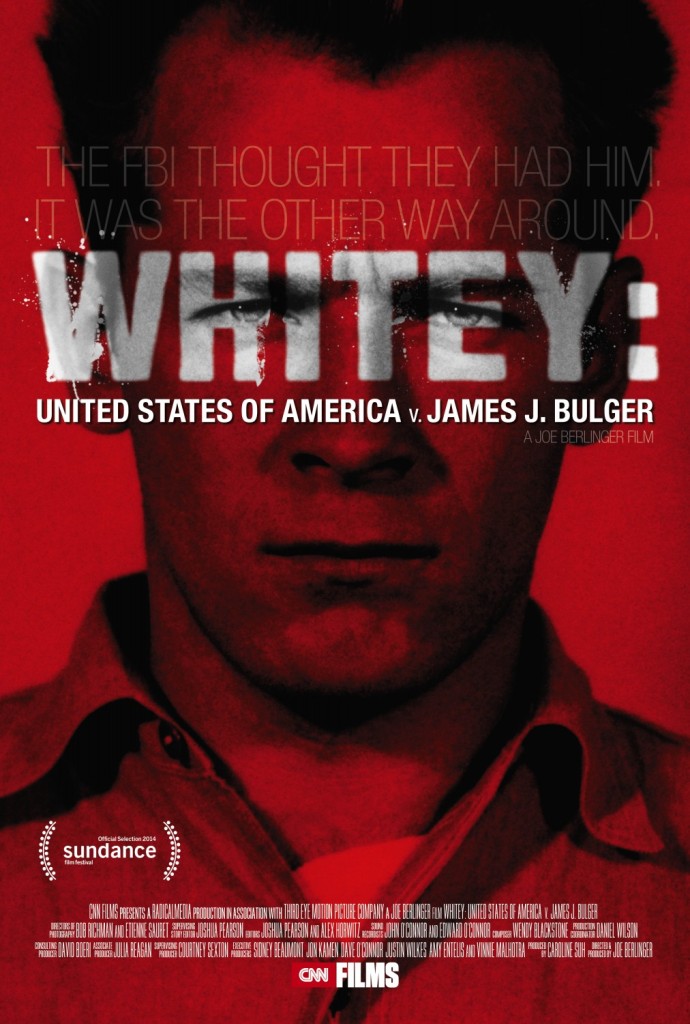

Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger (2014)

★★★★☆

Dir: Joe Berlinger

Magnolia Pictures (Official Site)

120 minutes

U.S. Theatrical Release: June 27, 2014 (Limited)

–

Just before Christmas in 1994, James “Whitey” Bulger, a big player in the so-called Irish Mafia in South Boston, was tipped off that the FBI had issued a warrant for his arrest. Having spent decades as an FBI informant, Bulger had cultivated plenty of friends in law enforcement, several of whom were happy to give him a head start in what would become 16 years of life on the lam. By the time he was finally caught and arrested in 2011, several individuals in the Boston office of the FBI were known to have ignored the crimes of the Irish Mafia — everything from extortion to theft to murder — in exchange for information from these gangsters that would allow them to take down the Irish Mafia’s biggest competitors: the Italian Mafia.

Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger is a startling new documentary that investigates the overwhelming deception, corruption and brutality of organized crime, not just by the gangsters, but by those in the FBI and Boston law enforcement who enabled them for decades. Boston FBI agent John Connolly, who grew up in Southie idolizing a teenaged yet already notorious Bulger, was especially involved in the perverse tit-for-tat that existed between the agency and the Irish Mafia. Connolly helped develop the Top Echelon Informant Program and promptly recruited Whitey, but ultimately gave him more information than the FBI ever got in return.

Once Bulger was apprehended and on trial, there was, of course, a catch: Bulger’s entire defense rested on his insistence that he was never an informant at all, that Connolly concocted the story to cover his own ass as he fed Whitey and his cronies information. As journalist David Boeri, one of dozens of interviewees in this documentary says, “The real story is: has our government enabled killers to run free?”

The film follows several witnesses against Whitey as they prepare to testify against him, people who were extorted by the gangster decades ago, who lost relatives to gangland murders in the 1970s and 1980s, all of whom have seen some of the FBI agents involved already punished, but are looking for some kind of final justice. Whitey does a terrific job of capturing their lives in a Southie where everyone knows everybody else, where there are no real secrets, and where a Southie son like Connolly is judged more harshly than the gangster he enabled.

Boasting terrific archival footage and photos that place the journalists, witnesses and other interviewees as being right in the middle of the action as it happened, Whitey recounts a fascinating and harrowing story. But it all starts to break down as more and more trust is placed in Bulger’s claims, and his lawyers all but say that he might as well be innocent, despite terrorizing an entire city and murdering people in cold blood, because the FBI were the real villains.

Most telling is the treatment of the prosecution as they are interviewed for the film. They’re all placed in a dark, empty room furnished with nothing but American flags, seated in hard plastic chairs without arms that are clumped uncomfortably close together. Bulger’s lawyer and other interviewees, however, are shown in natural settings: warm homes, cluttered offices, in casual dress with rolled-up sleeves. They all look approachable and believable, even Whitey’s own hitmen who testified against him, while the members of the prosecution team are made to look stiff and sinister. It’s an obvious and unnecessary trick, wholly unearned by the film, and the attempt to shift the majority of blame away from Bulger is disingenuous.

As the trial progresses, there are some genuine shocks for those unfamiliar with the case, and plenty of heartbreaking recollections from families ripped by Bulger and all his colleagues. But there are some stretches in here, too, some truths not told, a couple of instances of careful editing that border on staging a scene. Whitey is a good documentary, but it’s not the whole picture.

Splendid review, Stacia! I want to see this one so bad!

It’s a good one, I think you’ll really like it.